Sunken Treasures: The Curious Science of 7 Famous Shipwrecks

Sunken treasures

The oceans and coastlines of the world are scattered with thousands of shipwrecks that span thousands of years of history. By some estimates, less than 1 percent of all shipwrecks have been located, and only a small fraction of those have been explored or excavated.

For scientists and historians, each shipwreck is a vessel on a voyage from the past that continues with each new discovery — so let’s batten down the hatches and take a look at the science of some of the world’s most famous shipwrecks.

Mary Rose

The Mary Rose, one of the fastest and most heavily armed warships in the English fleet, sank in 1545 while leading the attack on a French invasion fleet at the mouth of Portsmouth Harbour, on England’s south coast. The only confirmed witness to the sinking reported that the ship rolled heavily after firing all its guns on one side and turned to fire the guns on the other side. Of around 400 crew and soldiers onboard, fewer than 40 escaped as the ship quickly filled with seawater and sank within a few minutes.

Historians and archaeologists still debate the cause of the sinking — the sea may have flooded the open lower gun ports, or the ship may have been overloaded with soldiers, guns and ammunition. One French account of the battle claimed that the Mary Rose was hit by enemy gunfire just before it sank, but no signs of such damage have been found, according to the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth.

The wreck of the Mary Rose was discovered in 1971 by a diving team investigating shipwrecks near Portsmouth. After its identity was confirmed, the wreck was excavated in a series of expeditions over 10 years by a team of more than 500 volunteer divers and support staff on shore. In 1982, the Mary Rose was brought to the surface for the first time in more than 400 years, in a purpose-built lifting frame attached to wires passing through the remains of the hull.

After one of the most costly and complex maritime preservation projects in history, about one-third of the ship’s original hull went on display at the Mary Rose Museum in 1986, along with many of the more than 28,000 artifacts excavated from within the wreck and on the surrounding seafloor. Archaeologists found hand weapons, cannons, tools and armor from the shipwreck, in addition to many personal items that belonged to the crew, such as clothing, coins and letters from home. These items have served as a time capsule of life in the English Tudor period.

Archaeologists have also studied the remains of more than 190 people found in the wreck. Many had suffered from diseases linked to childhood malnutrition, which researchers have interpreted as a sign of poor nutrition in the general population of England at the time. The skeletons of several crewmembers also showed signs of arthritis, likely caused by heavy lifting, and many healed bone fractures — occupational scars of a life of heavy labor at sea.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Mary Rose Museum was closed to the public in 2013 and opened again in July 2016 after an extensive redesign that now allows visitors to enter the top deck of the wreck through an "air lock" into the climate-controlled gallery. Several recently discovered artifacts from the shipwreck have also gone on display for the first time at the museum, including the painted wooden "Tudor Rose" emblem shown as the ship's figurehead in illustrations from the time.

USS Scorpion

In 1968, one the tensest years of the Cold War, the U.S. Navy was more worried than usual. In the first few months of that year, three foreign military submarines had gone missing in unexplained circumstances: one French, one Israeli, and the Soviet submarine K-129, thought to be armed with nuclear warheads. On May 21, 1968, the USS Scorpion was reported missing after failing to make a scheduled radio contact. The Scorpion was a U.S. Skipjack-class sub carrying 99 crewmembers and two nuclear-tipped torpedoes, each with a destructive power of 11 kilotons of TNT, and the U.S. Navy was determined to find the wreck before anyone else could.

The hunt for the USS Scorpion used a statistical method called Bayesian search theory to create search patterns over areas of the seafloor where the wreck was most likely to be found. The method had been developed less than two years earlier, in the search for a missing hydrogen bomb after an American B-52 bomber crashed off the coast of Spain in 1966, and is still used in search missions today.

In October 1968, U.S. Navy searchers located the wreck of the USS Scorpion, lying on the seabed in more than 9,800 feet (3,000 meters) of water, at the edge of the remote patch of the central Atlantic known as the Sargasso Sea. The Navy used an experimental remote-controlled submarine camera sled, an early forerunner of modern remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs).

The discovery of the wreck of the USS Scorpion prompted the U.S. Navy to reconvene a Court of Inquiry to focus on the possible causes of the sinking. A key piece of evidence was a burst of 15 distinct sounds recorded at the time the submarine went missing by an American underwater listening station in the Canary Islands. The recorded sounds were assumed to be noises from the implosion of the sub as it sank below its critical "crush depth," and an analysis of the sounds indicated that the Scorpion had imploded at a depth of around 2,000 feet (610 m) before sinking to the seafloor.

The Court of Inquiry was unable to find a conclusive reason for the sinking, and the tribunal ruled that the destruction of the USS Scorpion was caused by an "unexplained catastrophic event." Later studies of the wreck by U.S. Navy expeditions also found no signs that the submarine was attacked by an external weapon — a popular theory fueled by rumors that the Scorpion had been torpedoed by a Russian submarine in retaliation for spying.

The U.S. Navy monitors the wreck site of the Scorpion to test for radiation leaking from the submarine’s nuclear reactor and two nuclear warheads. So far, no radiation leaks have been reported and the Navy claims that the wreck has had no significant impact on the environment.

RMS Titanic

The discovery in 1985 of the world’s most famous shipwreck, the RMS Titanic, is curiously linked to the Cold War secrecy surrounding the wreck of a U.S. Navy nuclear-armed submarine, the USS Scorpion.

According to deep-sea explorer Robert Ballard, who led the team that found the Titanic, the successful search for the giant ship was funded by the Navy as a cover story for a secret mission to photograph and gather new data about the nuclear submarine wreck, including tests for radiation that may be leaking from its warheads or nuclear reactors. [Image Gallery: Stunning Shots of the Titanic Shipwreck]

After exploring and photographing the wrecks of the USS Scorpion and the USS Thresher, another U.S. Navy submarine that sank in the Atlantic in 1963, Ballard and his team on the Knorr, a research ship operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI), had just 12 days left to search for the wreck of the Titanic before they had to return to port, according to WHOI.

But the investigation of the submarine wrecks had provided the explorers with a vital clue: a sinking vessel leaves a trail of debris as it falls to the bottom of the ocean, with the heavier pieces sinking first, while lighter debris is spread in a comet-like tail on the seafloor, depending on the local currents.

Searchers on the Knorr used this detail to locate the wreck of the Titanic, just a few days before the end of the mission, by searching for the trail of debris left by the giant ship as she sank, Ballard told National Geographic magazine in 2008. Then, the researchers followed that trail back to the hull of the ship itself, now lying on the seabed in two parts, at a depth of 12,460 feet (3.6 kilometers) off the coast of Newfoundland.

The 1985 discovery of the Titanic wreck opened new scientific debates about the causes of the sinking. According to research published in 2008, metallurgical studies of samples recovered from the Titanic indicate that the rivets holding the ship’s hull together were not well made nor well placed during the ship's construction. The researchers suggested this poor riveting may have contributed to the damage to the hull caused by the impact with the iceberg.

Another study focused on iceberg activity in the North Atlantic shipping lanes in 1912, and refuted the idea that the Titanic sank in what was an exceptionally busy year for icebergs. One of the same researchers also studied the authenticity of several photographs claimed to have been taken of the iceberg that struck the Titanic.

Scientists have also studied the eventual fate of the RMS Titanic. Expeditions to the wreck have noted that the structure has rapidly deteriorated since it was discovered 31 years ago, and in the 1990s scientists began to study the stalactites of rust, or "rusticles" that grow from cracks and breaks in the hull.

Research published in 2010 found that the rusticles were filled with colonies of iron-eating bacteria, including a new species dubbed Halomonas titanicae, that are slowly devouring all the steel on the entire ship. The scientists predict that in less than hundred years, little will be left of the RMS Titanic but a few inedible brass parts and a large rusty stain on the ocean floor.

Vasa

The warship Vasa was the pride of the Swedish Navy when it was launched in 1628. Built on the orders of the King of Sweden Gustavus Adolphus for his expansionist war in Poland, and named for the Royal House of Vasa, it was magnificently equipped as one of the most powerful warships in the world. The Vasa set sail from Stockholm on Aug. 10, 1628, and barely traveled 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) before it foundered and sank, just 20 minutes into its maiden voyage and in view of the crowds on shore that had gathered to cheer its departure.

The wreck of the Vasa was rediscovered in Stockholm harbor in the 1950s, and in 1961 the wreck was secured in a lifting frame that allowed it to be moved into shallower water and excavated in stages. It was eventually removed to a dry dock after 18 months of recovery work and 1,300 dives. Since 1990, the wreck of the Vasa has been on display in a museum in Stockholm, where the timbers of the ship are constantly washed by a rain of preservatives to slow their decay.

The wreck of the Vasa is often compared to England's recovery of the Mary Rose shipwreck, another major maritime preservation project. But, the Vasa is about 100 years younger than the Mary Rose, and much more of its hull and detailed woodwork have survived the centuries under the sea. Marine archaeologists say the main reason for the Vasa's remarkable state of preservation was the heavily polluted waters of Stockholm's harbor until the 20th century, which created a toxic environment for microorganisms that break down wood, reported Wired.

The remains of more than 15 people and thousands of artifacts have been excavated from the wreck of the Vasa, including hand weapons, cannons, ship's tools, and six of the ship's 10 sails. Many personal items, such as clothes, shoes and coins, were also found on the well-preserved gun deck, where most of the crew had their berths.

Archaeologists and historians have studied the wreck of the Vasa to learn more about what caused it to sink. In 1995, a review of data from the wreck and historical archives proposed that late changes to the design of the ship while it was being built made the Vasa top-heavy — and that too little ballast had been loaded to stabilize the ship because it would have made the lower gun ports too close to the water. Despite fears that the ship sailed poorly during sea trials, it was ordered to war, and the instability of the ship quickly proved fatal when it was struck by a gust of wind and rolled over.

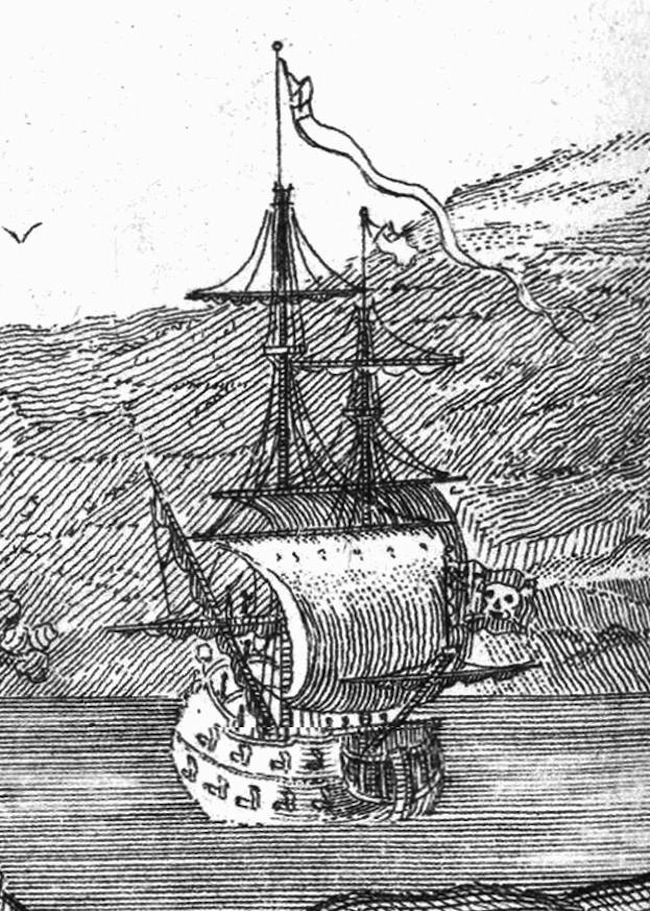

Queen Anne's Revenge

The Queen Anne's Revenge is one of the few wrecks of a verified pirate ship ever discovered. A former French slave carrier called La Concorde, it became the command of the feared English pirate Edward Teach, known as Blackbeard, after it was captured by pirates in 1717 near the island of Martinique. Blackbeard and his crew renamed the ship Queen Anne’s Revenge, and used it to plunder British, Dutch and Portuguese ships as they made their way to the Caribbean. [The Most Notorious Pirates Ever]

But in 1718, the Queen Anne's Revenge ran aground on a sandbar at "Topsail Inlet" — now named Beaufort Inlet — in North Carolina. Blackbeard escaped on a smaller ship, the Adventure, along with most of the treasure, leaving the Queen Anne's Revenge to the mercy of the waves. He was killed in hand-to-hand combat in November that year, after leading a boarding party onto a Royal Navy warship.

In 1996, the wreck of the Queen Anne’s Revenge was rediscovered, lying in about 28 feet (8.5 m) of water about 1 mile (1.6 km) offshore near Beaufort Inlet. Since then, it has been the focus of major underwater archaeology projects, with more than 250,000 individual artifacts recovered from the wreck. And while Blackbeard may have taken most of the treasure with him when he abandoned the Queen Anne's Revenge, the many items that were left behind have provided a rare glimpse into pirate life in the early 18th century.

So far, 31 cannons have been found in the wreck — far more than usual for a ship of its size — from several different European foundries, reflecting the mix of seized and recycled guns typical of a colonial pirate ship. Several cannons were still loaded with powder and shot when they were recovered, indicating they were ready for action when the ship was abandoned.

The artifacts from the wreck also include the remains of medical instruments and supplies, which, taken with historical records about Edward "Blackbeard" Teach, suggest he used some of the latest medical technology and knowledge of the time to keep his pirate crew in fighting shape.

USS Arkansas

The USS Arkansas was a dreadnought battleship that was deliberately sunk by an atomic blast during the U.S. Army's Operation Crossroads nuclear test program at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, near the equator in the Pacific Ocean.

The Arkansas was commissioned in 1912 and saw combat in the European and Pacific theaters of World War II, before it was sent in 1946 on its final mission: to serve as part of a target fleet for Operations Crossroads, a series of three bomb tests designed to learn the effect of a nuclear attack on ships at sea.

The Arkansas stayed afloat after the first test shot of Operation Crossroads, a 23-kiloton plutonium bomb dropped from a B-29 Superfortress that detonated in the air around 500 feet (152 m) above the target fleet. But for the second test shot, known as Shot Baker, the Arkansas was moored just 750 feet (230 m) from a second 23-kiloton plutonium bomb that was detonated at a depth of 90 feet (27 m) underwater — the first underwater nuclear device.

The result was an unexpectedly powerful explosion that instantly created a bubble of gas about 1,000 feet (300 m) across and lifted around 2 million tons of spray and seabed debris into the air. As the bubble rose above the surface, it was surrounded by a massive, hollow column of superheated spray. In the photograph of the Shot Baker explosion above, the dark streak on the right of the column of spray is the 26,000-ton USS Arkansas, pinned by her bows to the floor of the lagoon, before tumbling over into the spreading surge of turbulence.

The Crossroads Baker explosion has been called "the world's first nuclear disaster" — a few seconds after the explosion, water and seabed debris contaminated with radiation began to rain down on the target ships, and a tsunami of radioactive water and mist rolled away from the epicenter of the blast, coating the ships and the atoll with nuclear fallout — a new and alarming discovery. It proved impossible to decontaminate the surviving target ships that were still afloat, and the third nuclear test of Operation Crossroads was cancelled as a result.

Today, the wreck of the USS Arkansas lies among several other ships of the target fleet on the floor of Bikini Atoll, lying upside down in about 180 feet (55 m) of water. An Operation Crossroads report describes how the shock of the underwater blast was transmitted directly to the hulls of the ships below the waterline, and that the Arkansas appeared to have been "crushed as if by a tremendous hammer blow from below." Another target ship, the aircraft carrier USS Independence, remained afloat and was eventually towed back to the United States for further study, before being secretly scuttled near California's Farallon Islands in 1951.

The USS Arkansas is one of several shipwrecks at Bikini Atoll that are now visited by recreational divers. After 70 years — around 10 radioactive half-lives of the most dangerous nuclear contaminants — the waters and wrecks in Bikini Lagoon no longer present a significant radiation threat to swimmers or divers, according to scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

But Operation Crossroads left a lasting effect on the land of the atoll, where studies have shown that radioactive cesium from the nuclear blast has built up in vegetation, including coconuts and other food plants. As a result, Bikini Atoll has had no permanent inhabitants since the nuclear tests.

Antikythera wreck

In 1900, sponge divers exploring a rocky cove on the tiny Greek island of Antikythera discovered an ancient shipwreck lying in about 150 feet (50 m) of water. Their first dives recovered the arm of a bronze statue and other artifacts that caught the interest of archaeologists. In 1901, with assistance from the Greek navy and government archaeologists, divers recovered dozens of statues and other items from the wreck, including three corroded pieces of flat bronze — the first fragments of an extraordinary mechanical device known as the Antikythera Mechanism.

Studies of the Antikythera wreck suggest it was a Roman ship that sank between 70 B.C. and 60 B.C., during a voyage to Italy from the Roman domains in Greece and Asia Minor. It's likely the ship sank while sheltering from a storm in the cove, taking with it a literal fortune in fine art and other treasures that were possibly trade goods, gifts or plunder. After an excavation at the wreck in 2014, one researcher compared the ship to a "floating museum." [In Photos: Mission to 2,000-Year-Old Antikythera Shipwreck]

The ancient gears and dials of the Antikythera Mechanism make up one of the world's most celebrated archaeological artifacts, and demonstrate a level of mechanical sophistication in Greece and Asia Minor only hinted at in ancient records. The shoebox-size device, reconstructed from a total of 82 fragments, used 30 bronze gear wheels driven by a hand crank to move seven pointers representing the sun, moon and the five known planets around partitioned dials etched into its surface, in an approximation of their visible movements in the heavens. Research published in 2014 in the journal Nature found that the mechanism had been set to begin in 205 B.C.

Several inscriptions written on the bronze casing in ancient Greek text have been revealed as a sort of user manual for the mechanism, including a description of a mathematical method, based on a relationship between the lunar month and solar year known as the Metonic cycle, to calculate when an alignment of the moon and sun might result in an eclipse. The inscriptions also include an explanation of how the calendar divisions etched on the mechanism's dials relate to the cycle of Greek athletic games that were the inspiration for the modern Olympics.

Meanwhile, the ancient Antikythera wreck continues to give up new secrets to modern science.

Dives to the wreck between 2012 to 2014, under a collaborative project between the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in Greece and the U.S. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, recovered tableware, a lead anchor, and a bronze spear that may have been part of a statue of the goddess Athena. They also gathered spatial data about the site to create a 3D model of the seabed around the wreck, which will be used to guide future dives planned over the next five years. The future dives will include exploration of the wreck site with WHOI's diving robotic Exosuit, described as "Iron Man for underwater science."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus