Hair Spray vs. Ozone? Trump Makes Outdated Complaint

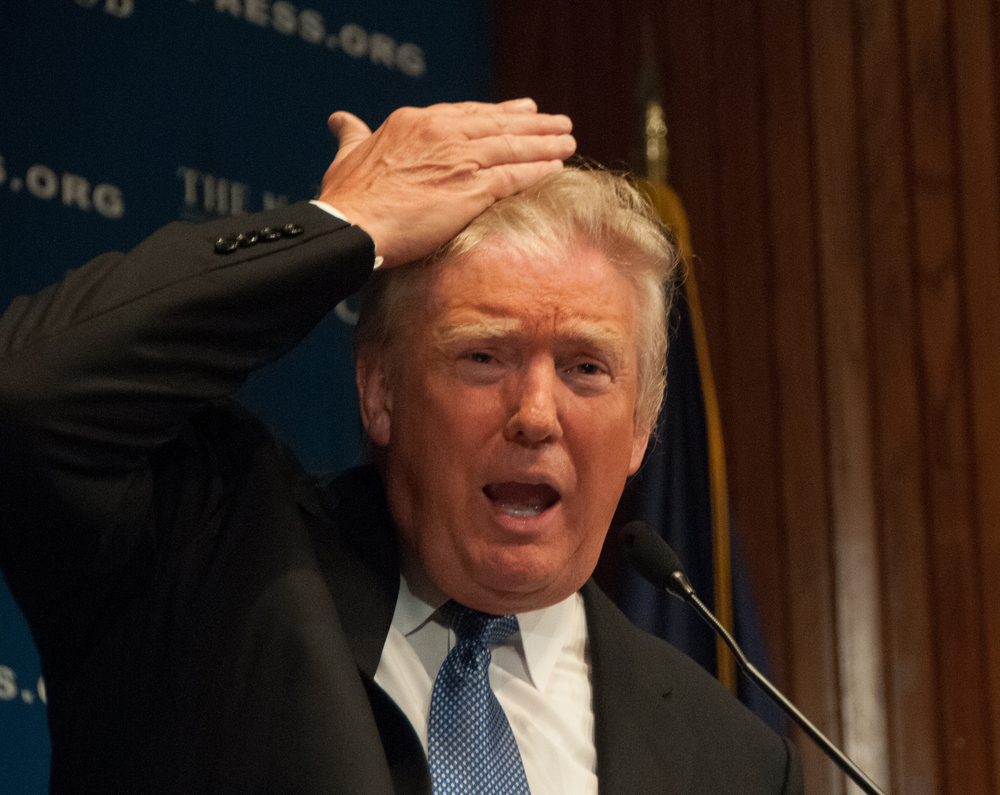

At a rally on Thursday in West Virginia, presidential candidate Donald Trump aired grievances over a product that appears to play a role in his daily life: hair spray.

"You know, you're not allowed to hair spray anymore because it affects the ozone," Trump said. "Hair spray's not like it used to be. It used to be real good," he added.

But does hair spray really still affect the ozone layer? [Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points]

The hair spray sold today is far less damaging than hair sprays in the past, because today's products do not contain chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, said Steven Maguire, a research associate at SNOLAB, an underground physics research facility in Ontario, Canada.

CFC molecules, which are made up of chains of carbon atoms with chlorine and fluorine atoms attached, acted as a propellant to force the liquid hair spray out of the can and disperse it into the air, Maguire told Live Science. Otherwise, hair spray would just be a liquid, he said.

The compounds were first developed the 1930s, Maguire said. At that time, scientists thought CFCs didn't react with any other compounds, he said. Researchers figured the substance was basically inert, he said. It wasn't until decades later that scientists realized CFCs react with ozone molecules, he said.

Ozone, which is made of three oxygen atoms bonded together, is the main component of one layer within Earth's stratosphere, located miles above the ground. The ozone layer plays an important role in the planet's climate by absorbing much of the sun's ultraviolent (UV) radiation, shielding the Earth below from those rays.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But when CFCs float up into the stratosphere, they react with UV rays, Maguire said. The reaction cleaves off one of the chlorine atoms of a CFC molecule, which in turn can react with ozone, breaking it down, he said. The problem is that after chlorine breaks down one ozone molecule, the chlorine is "spit out" and keeps going, breaking down more and more molecules of ozone, he said.

The more CFCs there are in the atmosphere, the more ozone is broken down, Maguire said. Eventually, when CFCs were being used in products, the rate of ozone breaking down was higher than the rate of ozone being formed, he said.

The problem was discovered in the 1970s, and CFCs began to be phased out, Maguire said. And in 1987, every country in the United Nations signed the Montreal Protocol, which called on countries to accelerate the reduction of CFCs in products, he said. [50 Interesting Facts About Earth]

But of course, hair spray still exists. So what's in it now?

One replacement for CFCs is hydrochlorofluorocarbons, or HCFCs, Maguire said. Instead of just chlorine and fluorine on the carbon chain, there's also a hydrogen atom, he said. And HCFCs propel hair spray out of the can just as well as CFCs did, he said.

But the extra hydrogen atom an HCFC molecule changes its chemistry in a way that lets the whole molecule be broken down and destroyed, Maguire said. Unlike CFC molecules, which can each break down many molecules of ozone, if HCFC molecules get up into the stratosphere, they might break down one ozone molecule, but then they would stop, he said.

Another replacement for CFCs is hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are carbon chains with fluorine and hydrogen atoms attached, Maguire said.

But hair spray isn't completely off the hook, environmentally. HCFCs still do break down into carbon dioxide, Maguire said. (However, the carbon dioxide output of the hair spray industry is very small compared to what comes from the burning of fossil fuels, he added.) So while modern hair spray fixes the ozone problem, it can contribute to other things, Maguire said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated on May 9 to include information on HFCs.

Follow Sara G. Miller on Twitter @saragmiller. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus