Zika Revealed: Here's What a Brain-Cell-Killing Virus Looks Like

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

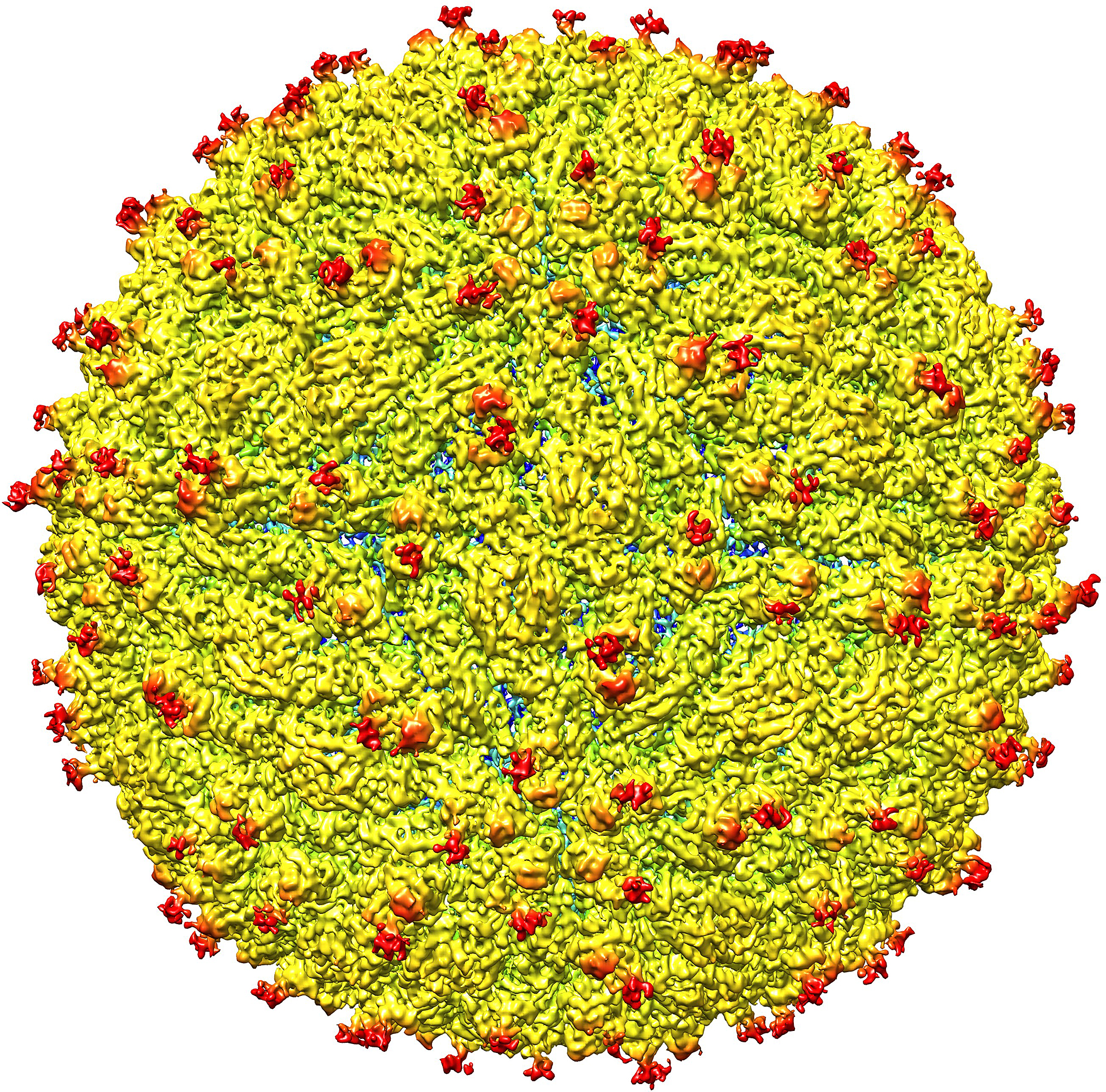

The destructive Zika virus has been visualized for the first time, shedding light on similarities and differences between this and related viruses, according to a new study.

The new findings may be helpful in developing effective antiviral treatments and vaccines against the Zika virus, the researchers said.

"The structure of the virus provides a map that shows potential regions of the virus that could be targeted by a therapeutic treatment, used to create an effective vaccine, or [used] to improve our ability to diagnose and distinguish Zika infection from that of other related viruses," Richard Kuhn, the director of the Purdue University Institute for Inflammation, Immunology and Infectious Diseases in Indiana and a co-author on the study, said in a statement.

"Determining the structure greatly advances our understanding of Zika, a virus about which little is known," he said. [Zika Virus News: Complete Coverage of The Outbreak]

Although the Zika virus usually causes mild or no symptoms, health officials are concerned about a link between Zika infection in pregnant women and a birth defect called microcephaly, or an abnormally small head.

The transmission of the Zika virus has so far been reported in 39 countries and territories. Of these locations, Brazil and French Polynesia have reported an increase in microcephaly, according to the World Health Organization. In addition, 12 of the locations with Zika cases have reported increases in cases of a rare neurological condition called Guillain-Barré syndrome, which causes muscle weakness and, sometimes, paralysis in kids and adults.

In the new study, researchers looked at a strain of the virus isolated from a patient who had been infected with Zika during an epidemic in French Polynesia in 2013-14.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that the structure of the virus is very similar to that of other flaviviruses, a family of viruses that also includes dengue, West Nile and yellow fever. The structure of the Zika virus appeared to be particularly similar to the structure of dengue, the study said.

"In essence, all these viruses have the same shape and structure, but they enter different kinds of cells," and therefore lead to different illnesses, said Michael Rossmann, a professor of biological sciences at Purdue University and a co-author on the study.

However, the researchers did find a certain structural difference between Zika and these related viruses. That difference is found in an area of the virus that may be important for how the virus attaches to human cells, which types of cells it may enter and how the resulting disease may progress. [5 Things to Know About Zika Virus]

There is an equivalent of this particular area found in the dengue virus, and it is involved in how that virus attaches to human cells. If the Zika virus's version of this area serves the same function as in dengue, and is therefore also involved in attachment to human cells, that suggests a possible treatment, Rossmann said. "Perhaps an inhibitor could be designed to block this function and keep the virus from attaching to and infecting human cells," Rossmann told Live Science.

It is also possible that this area of structural difference is somehow involved in the association between Zika virus infection and improper brain development in fetuses, but more research is needed to investigate this question, the researchers said.

Though the researchers now have a much better understanding of what the virus looks like, efforts to actually inhibit it may take a long time, Rossmann said. "People should not expect a sudden result," he said.

The new study was published today (March 31) in the journal Science.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus