10-Million-Year-Old Snake Revealed in Living Color

The fossilized remains of a snake that lived 10 million years ago don't look very colorful to the naked eye today. But preserved within are cell structures that revealed to scientists the colors that would have dappled its skin while the animal was alive.

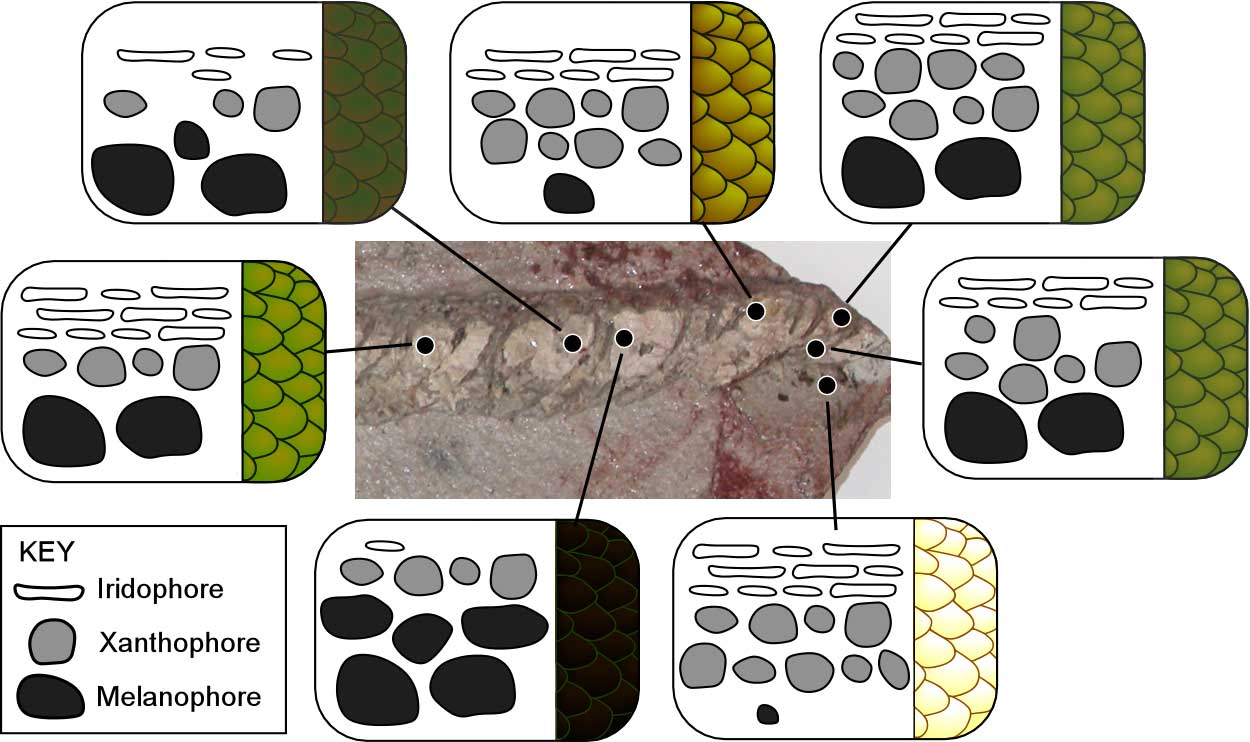

Though the pigment grains held within the snake's cells were long gone when scientists discovered the fossil, the cell shapes resembled several types of pigment cells in modern snakes that contain various kinds of color information.

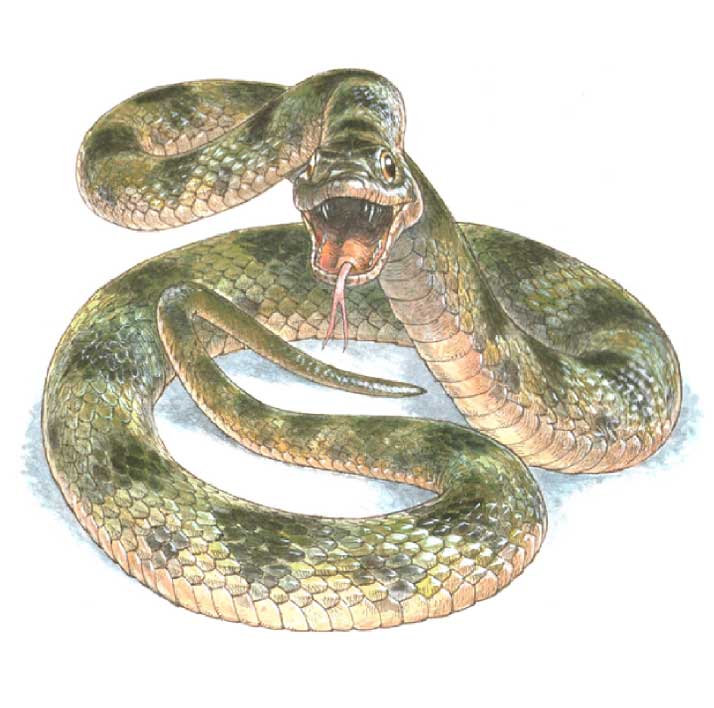

Matching the ancient and modern cell shapes allowed researchers to use modern snake color cell data as a road map. They described the hue of the fossilized snake's back as green mixed with blotches of brown-black and yellow-green, with a pale, creamy shade extending along its belly. [Image Gallery: Snakes of the World]

A snake of a different color

Modern snakes have three different types of pigment cells, or chromatophores, arranged in layers in their skin: iridophores at the top, then xanthophores, and melanophores at the bottom, with each containing a different type of granule related to color.

But the abundance and distribution of these pigment cells vary across a snake's body, which produces the color patterns in different body regions.

On the skin of the fossilized snake's belly, for example, the only chromatophores the scientists found were iridophores. In modern snakes, these scatter light and are associated with white and cream hues, according to the study's lead author, Maria McNamara, a paleobiologist at the University College Cork, in Ireland. In other areas of the skin across the snake's body, xanthophores and iridophores were abundant, and melanophores were rare, hinting at patterns of yellowish-green, McNamara said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Skin deep

The secret to the exceptional quality of those preserved cell structures lies in the process that fossilized the snake: mineralization, McNamara explained.

In previous studies of color extraction from fossils, scientists had reconstructed pigments from traces of melanin (produced by melanophores) preserved in both feathers and skin, McNamara told Live Science.

Those surviving melanin traces represented only a partial picture of an animal's color palette, as other types of pigment-producing structures are typically destroyed during the most common type of fossilization that preserves leftover carbon-based residue. But after this snake died, it was preserved by mineralization, with calcium phosphate crystals growing within its decaying tissues.

"Instead of the organic residues of the tissues being fossilized, the entire tissue has been fossilized in mineral," McNamara said.

And as McNamara and her colleagues discovered, that mineralization left behind a fossil that retained the shapes of cells linked to skin color.

"Up until now, all attempts to reconstruct fossil color have used organic fossils — fossils where soft tissue was preserved as organic residue. Nobody had looked at mineralized fossils before," McNamara said.

"Mineralized fossils not only preserve evidence of melanin, but they preserve evidence of other types of colors as well," she added.

Colorful portraits

In addition to providing multihued portraits of these long-ago reptiles, deciphering an ancient snake's color could provide scientists with a clearer picture of how it interacted with its habitat, and could inform scientists' understanding of how colors and patterns evolved in modern snakes, the study authors suggested.

In modern snakes, colors vary from a coral snake's vivid bands to drab camouflage (think dusty-hued rattlesnakes) to iridescent (like rainbow boa constrictors), and their colors and patterns can look different when the snake is slithering, said David Kizirian, a curatorial associate of herpetology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, who was not involved in the current study.

And there is still much to be learned about how colors in snakes evolved and even what they’re used for, Kizirian said.

Knowing that mineralized fossils could retain a lot more color information than scientists had previously suspected could be an important part of answering questions about how snakes evolved and use their color — today and millions of years in the past.

The findings were published online today (March 31) in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.