Samurai Secrets: 1888 Martial Arts Manual for Cops Revealed

A newly translated 19th-century book, written by samurai, describes martial arts techniques designed to help police officers of the time. The highly guarded practices included how to tie suspects up using paper string and fighting techniques that allowed officers to defeat suspects without killing them.

The book, which contains illustrated instructions, was published in 1888, a time when the samurai class had lost many of its privileges and the formally secretive martial art schools that taught the samurai were willing to divulge their secrets.

This book drew on the expertise of 16 martial arts schools operating in Japan in 1888. "Each school revealed their inner secrets and demonstrated their expertise," wrote Tetsutaro Hisatomi, the author of the book and a samurai himself. Those techniques deemed helpful to police officers were "incorporated into this volume which we have decided to call 'Kenpo,' or 'Fisticuffs,'" wrote Hisatomi, according to the translation by Eric Shahan, who specializes in translating 19th- and 20th-century Japanese martial arts texts. [See Images from the 'Illustrated Martial Arts Book]

At the beginning of the book, a samurai named Ohara Shigeya urges those who are studying to become police officers to use the techniques without causing unnecessary harm.

"Things granted to us by heaven should not be wasted or used carelessly," wrote Shigeya. "Life is precious. One should walk the road of charity and benevolence. The crime should be hated, not the person. Everything should be based on the law."

Decline of the samurai

In 1868, the Japanese shogun (a hereditary ruler) was overthrown and Japan's government became centralized under the emperor in an event known as the Meiji Restoration. A series of military reforms followed the restoration and included the samurai class gradually losing its privileges.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Works like Kenpo with step-by-step illustrations weren't really around until after the Meiji Restoration. They were made in response to declining interest in martial arts," said Shahan. "Some groups began to publish information in a manner accessible to the general public. All this was an effort to encourage people of the benefits of martial arts training."

Samurai teaching the police

The illustrations in the book often show a police officer armed with a sword. Neither the police officer nor the assailants is shown using firearms. [In Photos: The Western Martial Art of the Sword]

"The left hand should always be holding the 'tsuka,' or handle of the sword, while the right hand hangs at your side," wrote Hisatomi.

The book contains several techniques for preventing an assailant from taking hold of a police officer's sword. In the book, the officer never uses the sword to slash at the suspect, instead using a variety of blocks, holds, strikes and throws to stop the suspect without killing him.

Hisatomi highlights the importance of correct breathing and posture, noting that power comes from the abdomen, not the chest. "Your power should all be in 'saika,' just below the navel, and indeed, the abdomen as a whole should be filled with this power."

Don't forget the rope

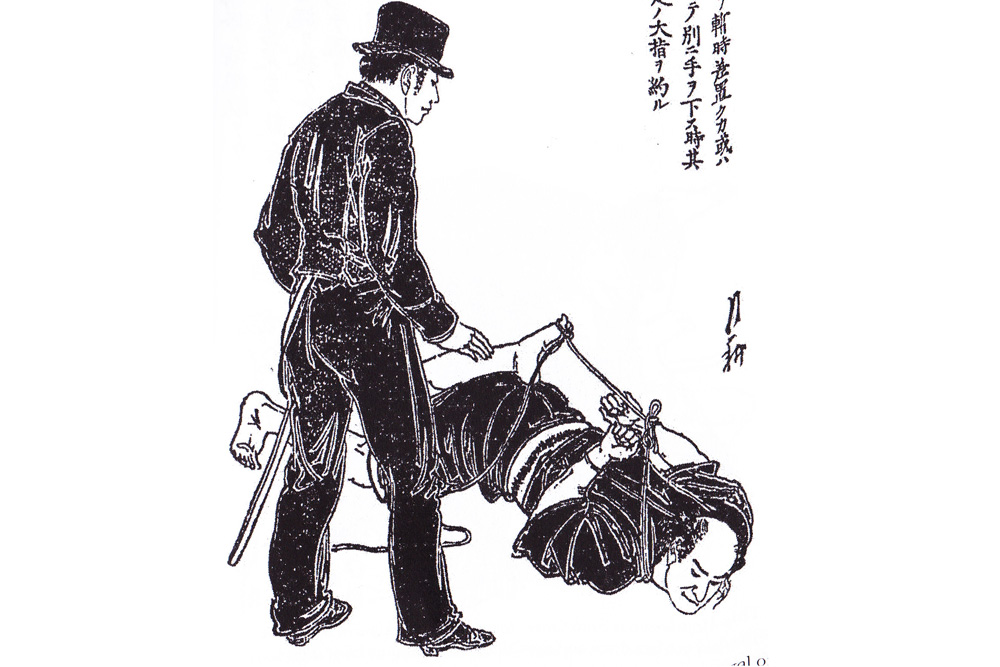

Hisatomi doesn't mention handcuffs and instead has a section on "hojo" rope-binding techniques. "Hojo is typically done by threading the cord to restrain the right arm first," wrote Hisatomi, noting that the majority of people are right-handed. "His right arm should always be forced to your left."

Hisatomi noted that it is important for an officer to carry enough rope when on duty.

In case an officer didn't have enough rope, or forgot to bring it, Hisatomi wrote that one should "tie the middle fingers together at the base with a double knot," by using "motoyui," which is "a paper cord used for tying hair up" or "kamiyori," which is a "general-use kind of paper string."

The accompanying illustration shows a person with the two middle fingers tied tightly together.

Resuscitation secrets

In addition to fighting and rope-binding techniques, there is a section on "kappo," which are resuscitation techniques. These could help police officers heal people who had been in accidents, such as nearly drowning or falling off carts.

"Traditionally, the way these methods are done is kept secret by the various 'ryuha' [martial art schools]," Hisatomi wrote. One of the kappo techniques, called "tanyu," can "be applied to a person who has become suffocated by water and drowned," wrote Hisatomi.

The author said that the left shinbone should be planted firmly on the ground while the right shinbone should be against part of the victim's back, behind the solar plexus.

Both arms are passed beneath the victim's armpits, and both hands are placed slightly below the navel. "Joining the hands together at this point, you should pull backwards and up. At the same time, press in hard with the shin," Hisatomi wrote.

Useful today?

Some of the techniques, Shahan said, could be beneficial to modern-day police officers.

"All the [fighting] techniques deal with responding to sudden lunging attacks. Being familiar with techniques for defending against such attacks as well as joint manipulation would seem to be of use," Shahan said.

However, Shahan advised against today's cops using throws to take down a suspect. "Throwing techniques might not be good, as they allow the attacker to make contact with the body, potentially enabling them to seize a weapon on the officer's belt."

Shahan, who holds a San Dan (third-degree black belt) in Kobudo, has self-published his English translation of the training book.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus