New Seafloor Map Reveals Secrets of Ancient Continents' Shoving Match

Tectonic plates may have inched across the Earth’s surface to where they are now over the course of billions of years, but they left behind traces of this movement in bumps and gashes under the sea. Now, a new topographic map of the seafloor has helped researchers chronicle when the Indian-Eurasian continent formed as well as find a previously undiscovered microplate that broke off as a result of the event.

NASA’s Earth Observatory released the map on Jan. 13, and it reveals the complex topography of the planet’s seafloor. By analyzing these underwater peaks and ridges, researchers can decipher how and when the plates that made up the ancient supercontinent Pangaea tore apart about 200 million years ago, resulting in the birth of new ocean crust and the formation of mountain ranges.

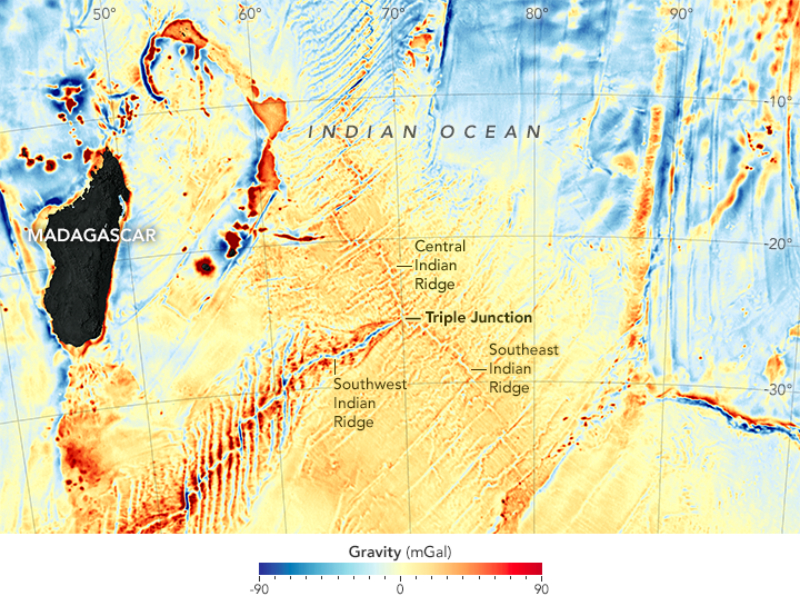

The map, which is bright blue and red like a heat map, was compiled by an international team of researchers using a gravity model of the ocean, which is in turn based on altimetry data from the CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 satellites. [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

Altimetry measures the height of the sea surface from space by timing how long it takes a radar signal to reflect off the ocean and return to the satellite. The subtle highs and lows of the ocean surface mimic both seafloor topography and Earth’s gravity field, according to NASA.

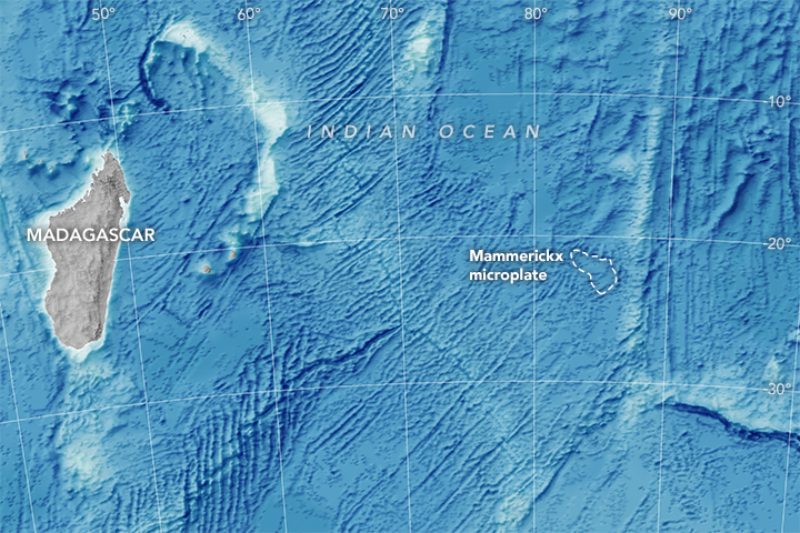

The researchers used this data to discover a new piece of the puzzle: a microplate that had broken off from larger tectonic plates. The newly discovered Mammerickx Microplate, named after a pioneer in seafloor topography (Jacqueline Mammerickx), is the first to be discovered in the Indian Ocean. It is roughly the size of West Virginia or Tasmania, and its existence helped the scientists establish that the collision between the Indian plate and Eurasia — which led to the formation of the Himalayas and Mount Everest — began about 47 million years ago.

About 50 million years ago, the Indian plate was moving as fast as a tectonic plate can go — roughly 6 inches (15 centimeters) per year. When the Indian plate struck Eurasia, the entire plate slowed down and changed direction, which can be seen in the ridges in the seafloor to the south, where the Indian plate meets the Antarctic plate. The researchers were able to examine these seafloor ridges to recreate the stress the impact placed on the plate. That stress eventually ripped off a small piece of the Antarctic plate, resulting in the Mammerickx Microplate, spinning it like a ball bearing until it came to rest where it is today.

The researchers say that the same seafloor map can be used for further research on tectonic plates. But, submariners and ship captains can also use it for navigation. And with a resolution that captures detailed features as narrow as 3 miles (5 kilometers), it could also potentially be helpful to prospectors searching for oil, gas and mineral resources.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Knvul Sheikh on Twitter @KnvulS. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.