Micro Mollusk Breaks Record for World's Tiniest Snail

An itsy-bitsy mollusk in Borneo is the new record holder for the world's smallest known snail, a new study finds.

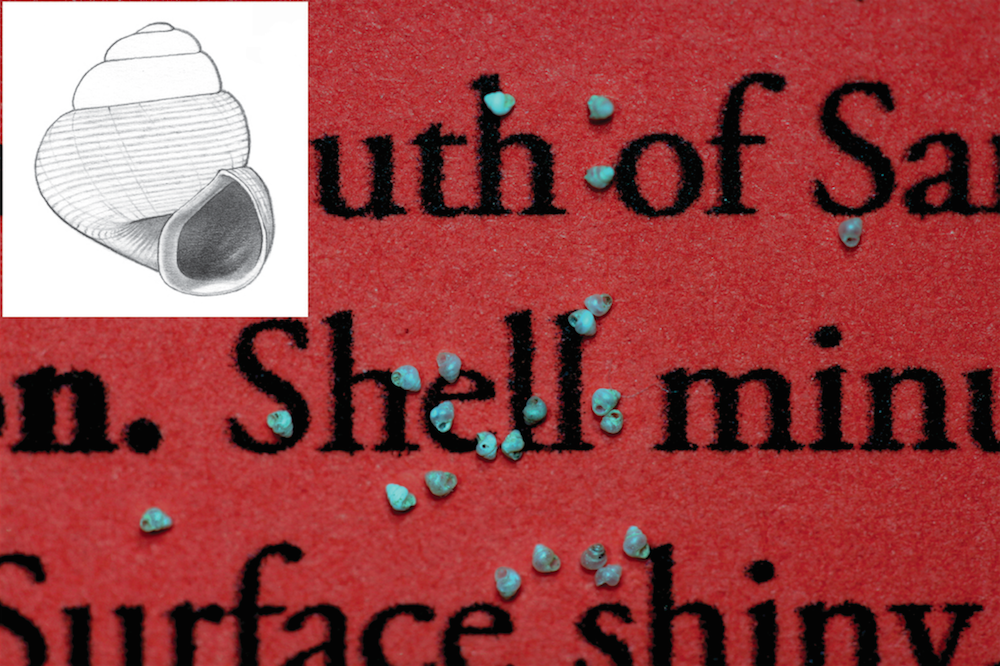

Its shiny, translucent, white shell has an average height of 0.027 inches (0.7 millimeters), breaking the previously held record by about a tenth of a millimeter. The former champion — the Chinese snail Angustopila dominikae —is the world's second-smallest snail, with an average shell height of 0.033 inches (0.86 mm), the researchers said.

Dutch and Malaysian researchers named the newfound snail Acmella nana; its species name (nana) is a reference to the Latin nanus, or "dwarf." Acmella nana is so small that the researchers couldn't see it in the wild without a microscope. [Amazing Mollusks: Images of Strange & Slimy Snails]

But the researchers knew exactly where to hunt for unknown mollusks: Snails tend to live on Borneo's limestone hills, likely because their shells are made of calcium carbonate, the main component of limestone, said study co-researcher Menno Schilthuizen, a professor of evolution at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

"When we go to a limestone hill, we just bring some strong plastic bags, and we collect a lot of soil and litter and dirt from underneath the limestone cliffs," Schilthuizen told Live Science.

They sieve the contents, and dump the larger objects (including the snail shells) into a bucket of water. "We stir it around a lot so that the sand and clay sinks to the bottom, but the shells— which contain a bubble of air — float," Schilthuizen said.

Then, they scoop out the floating shells and sort them under a microscope.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"You can sometimes get thousands or tens of thousands of shells from a few liters of soil, including these very tiny ones," he said.

It's unclear what Acmella nana eats, because the researchers have never seen it alive in the wild. But the researchers have observed a related snail species from Borneo, Acmella polita, foraging on thin films of bacteria and fungi that grow on wet limestone surfaces in caves.

"Probably, Acmella nana lives in a similar way," Schilthuizen said.

The new tiny record holder lives in at least three places in Malaysian Borneo. (The island of Borneo is divided among three countries: Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia.) So, it's unlikely that it will be wiped out if one of its environments is destroyed. However, other snail species are not so lucky, Schilthuizen said.

There is a lot of calcium carbonate in the tropics (in fact, the calcium carbonate there is made from ancient mollusk shells), but it erodes rapidly, leaving behind isolated peaks of limestone, Schilthuizen said. As species are secluded on limestone peaks, they evolve into new species.

Borneo boasts a high diversity of snails — possibly up to 500 species — but these native creatures can be wiped out if developers or other disturbances destroy a limestone habitat, Schilthuizen said.

For instance, "A blazing forest fire at Loloposon Cave could wipe out the entire population of Diplommatina tylocheilos," Schilthuizen said in a statement, referring to a snail whose sole habitat lies in that cave.

Many of these limestone hills are being quarried for cement, and Schilthuizen and his colleagues have already documented native snail species that have gone extinct after their entire habitats were destroyed. Perhaps, he said, these companies could quarry just part of a hill and leave the other part untouched to promote the continuation of these species.

Snails play an important ecological role, feeding on dead and decaying matter, Schilthuizen said.

In addition to Acmella nana, researchers discovered another 47 snail species in the study, published online today (Nov. 2) in the journal ZooKeys.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.