Psychedelic Swirls Show Algae Bloom from Space

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

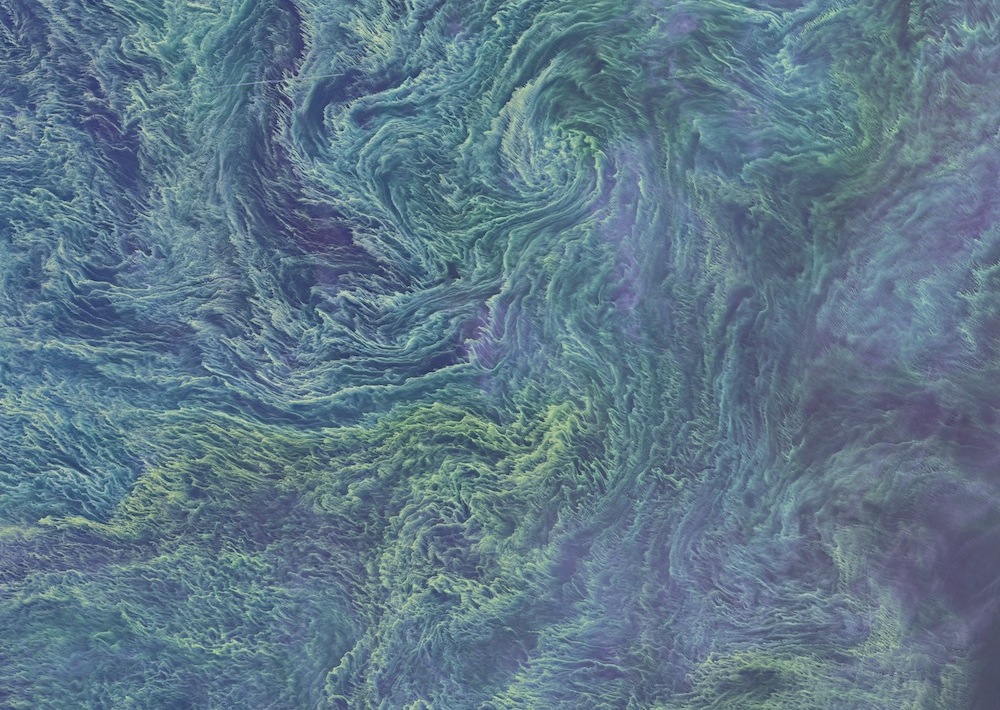

Psychedelic swirls decorate the Baltic Sea in a stunning new satellite image.

The Operational Land Imager on the Landsat 8 satellite snapped the image on Aug. 11, according to NASA's Earth Observatory, when land-based observers reported massive blooms of cyanobacteria. These bacteria are also called blue-green algae, though they aren't actually algae at all; they're an ancient family of bacteria that get their energy from the sun, via photosynthesis.

The summer Baltic is prime cyanobacteria territory, according to NASA: Sunlight is abundant, and the waters are nutrient rich. [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

Though scientists can't diagnose a specific type of bloom from satellite observations alone, the Earth Observatory contacted Maren Voss, a phytoplankton researcher at the Leibniz Institute of Baltic Sea Research, who was on a ship in the Baltic when this image was taken. Voss told the Earth Observatory that a type of cyanobacteria called Nodularia was present in the bloom, which floated on the ocean surface like a carpet.

Cyanobacteria were the first organisms to develop photosynthesis, a talent they acquired some 2.4 billion years ago, scientists have said. The waste product of this process — oxygen — altered Earth's atmosphere drastically, paving the way for complex life.

Cyanobacteria also made plants possible. Chloroplasts, the organelles in plant cells that drive photosynthesis, are descendants of cyanobacteria. At some point, a single-celled organism engulfed a cyanobacterium, which thrived inside its would-be devourer. The cell, too, benefited from the cyanobacteria's photosynthetic ways. This "endosymbiotic event" led to the evolution of algae and plants.

Mitochondria, the engines of animal cells, were primitive bacteria taken up in a similar way. Both mitochondria and chloroplasts have their own DNA, which is organized in a circular structure like that of most bacteria.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Blooms like the one seen in the Baltic are part of ocean life, but there is evidence that humans can cause particularly large blooms by over-fertilizing the sea. This happens through nutrient runoff, or in the case of the Baltic, when cruise liners dump wastewater directly into the ocean. Climate change may also make blooms worse, because the bacteria thrive in warm water.

Cyanobacteria blooms can be a problem both because they can suck up all the oxygen in a region, creating marine "dead zones" where nothing else can live, and because some cyanobacteria are toxins. Certain species of cyanobacteria produce neurotoxins, which attack the nervous system. One class of cyanobacteria toxins, microcystins, can cause tumor development after chronic exposure, according to a 2009 review published in the journal Interdisciplinary Toxicology. And Nodularia, the species identified in the Baltic bloom, produces hepatotoxins, which cause damage to the liver.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus