Photos: Hummingbirds Slurp Up Tasty Nectar

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hummingbirds zip from flower to flower, licking up nectar with their tongues. The exact way these tongues work has long eluded scientists, but a new study shows that hummingbird tongues are elastic micropumps that rapidly pull in nectar once they reach the inside of the flower. [Read the full story on the hummingbird's tongue]

Sparkling violetear

A male sparkling violetear (Colibri coruscans) hummingbird in Bogotá, Colombia. The bird has extended its tongue after feeding from a flower, preparing it for elastic expansion. Hummingbirds fuel their high-speed lifestyle with tiny drops of nectar and the occasional fly. (Image credit: Kristiina Hurme)

Black-throated mango

A male black-throated mango (Anthracothorax nigricollis) hummingbird in Finca El Colibrí Gorriazul, Fusagasugá, Colombia. Hummingbirds can extend their long, skinny tongues twice as far as the bill, which helps them reach nectar deep inside flowers. (Image credit: Kristiina Hurme)

Pretty plumage

A female black-throated mango hummingbird photographed in Finca El Colibrí Gorriazul, Fusagasugá, Colombia. Hummingbirds' tongues are forked at the tip, and the tips expand inside the flower to trap nectar. Hummingbirds feed on long, tubular flowers that make nectar hard to reach. (Image credit: Kristiina Hurme)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Juvenile hummingbird

A juvenile male black-throated mango hummingbird in Finca El Colibrí Gorriazul, Fusagasugá, Colombia. Without the use of any muscles or nerves, a hummingbird's tongue can rapidly expand to pull in nectar from a flower. (Image credit: Kristiina Hurme)

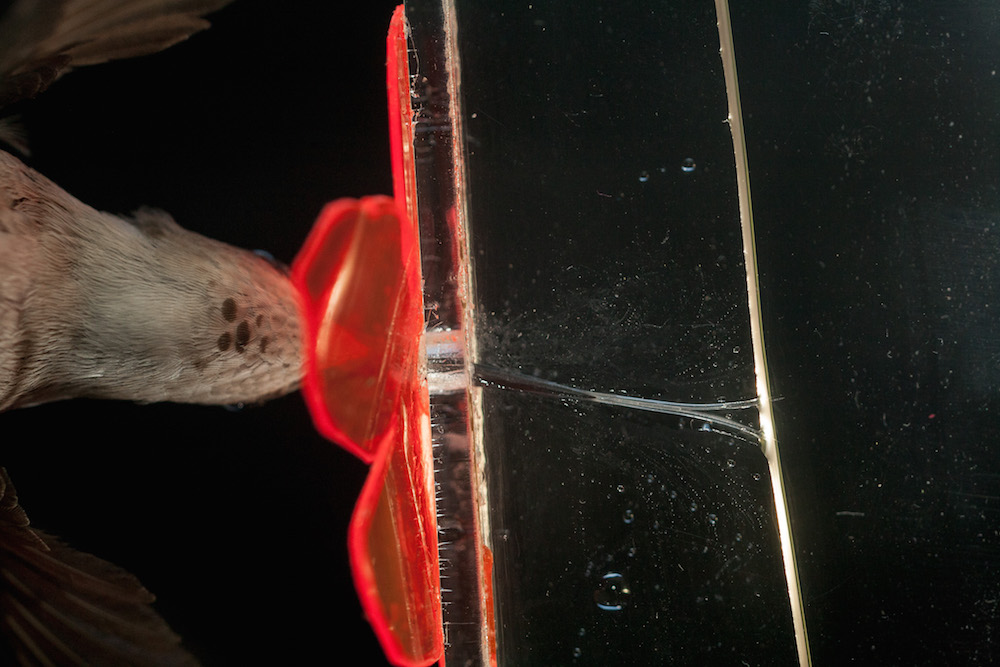

Split second

A high-speed image of a black-chinned hummingbird (Archilochus alexandri) photographed near Las Vegas. Notice the fork-tipped tongue. Hummingbirds are so fast they can empty a flower's nectar in less than a second. (Image credit: Don Carroll)

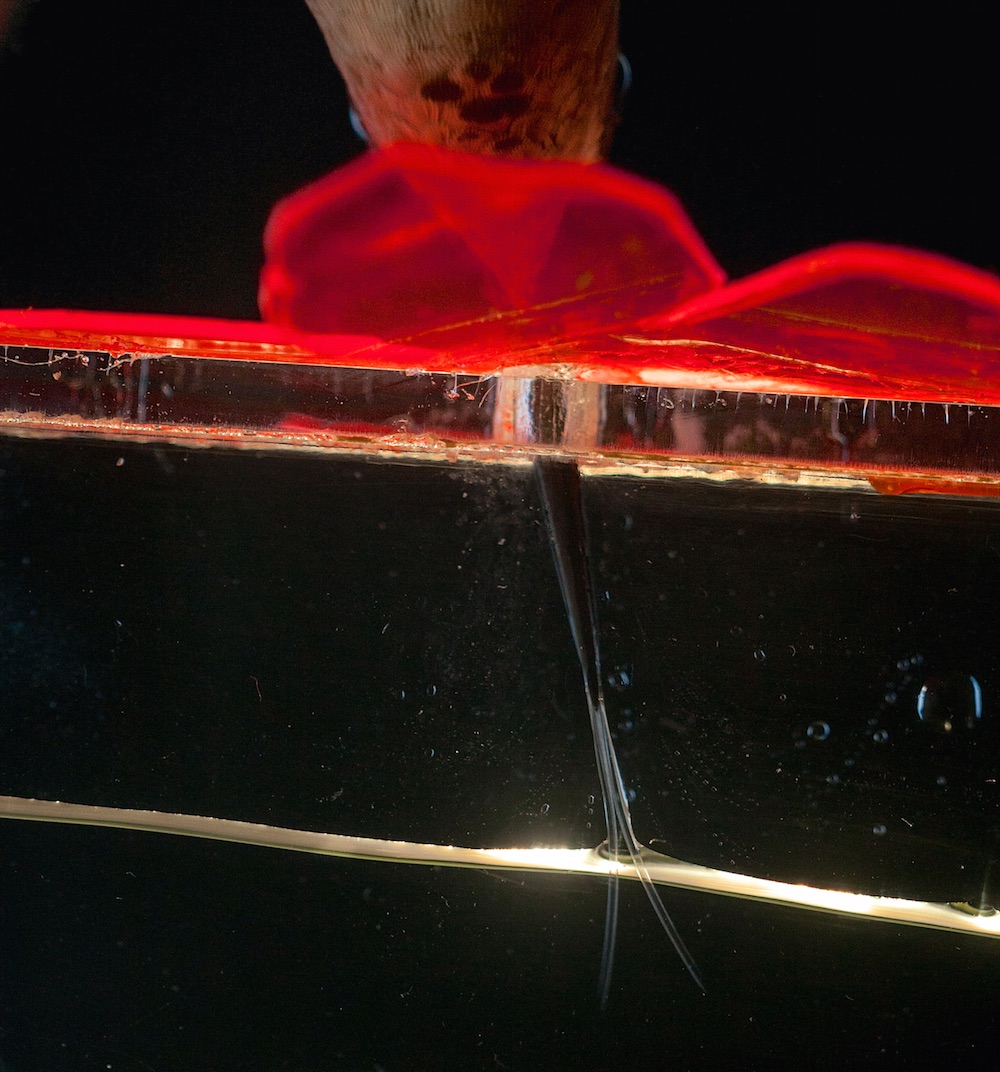

Nectar snack

Another image of a black-chinned hummingbird feeding on artificial nectar from a transparent tube. When hummingbirds drink, they are licking 15 to 20 times per second. The amazing speed at which hummingbirds can drink is possible due to the physics of the elastic micropump, the researchers said. (Image credit: Don Carroll)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus