10,000 Monitored for Ebola in US Over Fall & Winter

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

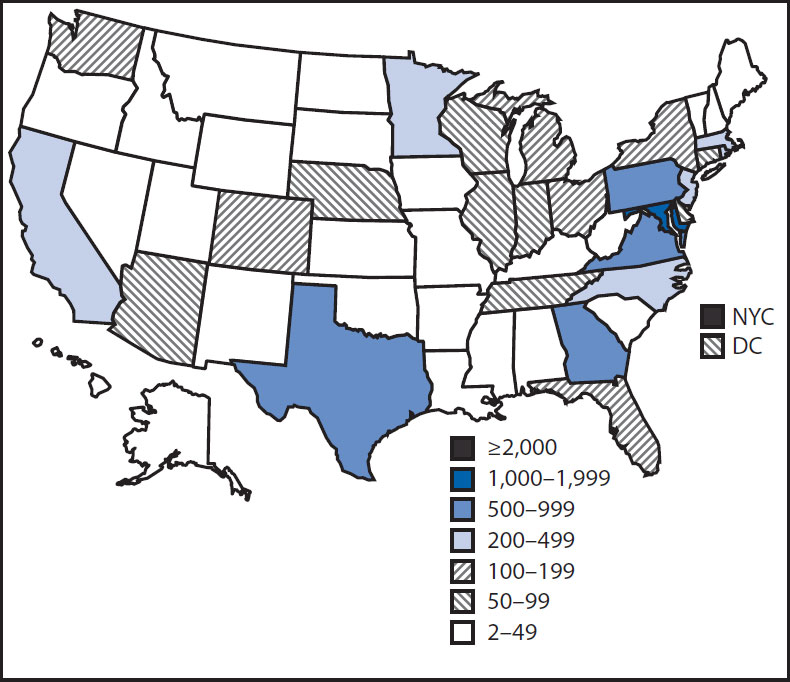

More than 10,000 people in the United States were monitored for symptoms of Ebola this past fall and winter, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In late October, the CDC recommended that everyone in the United States who had possibly been exposed to Ebola — including people returning from an Ebola-affected country, as well as those who cared for Ebola patients here — be monitored for 21 days after their last exposure for symptoms of the disease.

Within a week, all 50 states were following these guidelines. The people being monitored took their own temperatures twice a day, and reported their health status to a public health official at least once daily. Those deemed at high risk for Ebola infection reported their health status twice daily, and had an official come by to check on them in person at least once a day.

From November to March, 10,344 people were each monitored for 21 days for symptoms of Ebola, according to the new report.

During an average week within that period, about 20 of the people being monitored (1.2 percent) reported having symptoms that could have been due to Ebola, with the highest number being reported in December. Nearly 40 people were tested for Ebola during their monitoring period, but none tested positive for the disease. [What Are the Long-Term Effects of Ebola?]

Less than 1 percent had "incomplete monitoring," meaning that there were gaps in their monitoring of more than 48 hours.

"These results provide evidence of successful U.S. monitoring for Ebola," the researchers wrote in their report. "Jurisdictions demonstrated public health capacity to rapidly conduct and effectively monitor thousands of persons over a sustained period," they said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Given the complexity and amount of coordination of effort required, the Ebola monitoring program in the United States provided systemic evidence of the capability of state, territorial, and local health departments to ensure and protect the health of the U.S. public," the researchers said.

The study is published this week in the CDC journal Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus