Oddball 'Crystal' Survived Crash to Earth Inside Meteorite

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

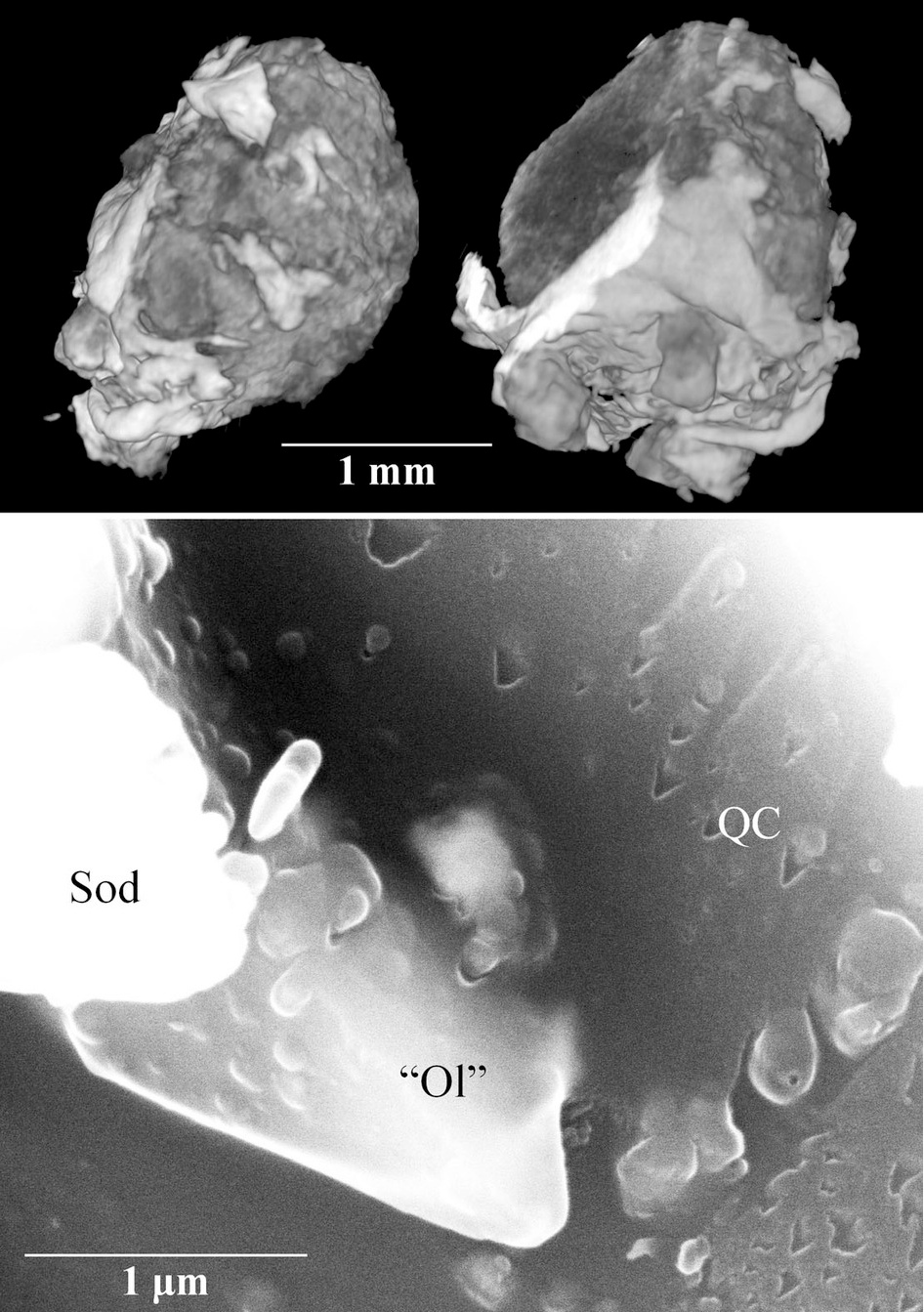

A bizarre crystal-like mineral recently found in a meteorite that crashed to Earth perhaps 15,000 years ago adds more support for the idea that the fragile structure can survive in nature. But how it formed at the beginnings of the solar system is still a mystery.

The newfound mineral is called a "quasicrystal" because it resembles a crystal, but the atoms are not arranged as regularly as they are in real crystals. The quasicrystal hitched a ride to Earth on a meteorite that zipped from space through Earth's atmosphere and crashed to the ground. That process is generally a violent one that heats up the insides of rocks, making the delicate quasicrystal's survival a surprise.

"The difference between crystals and quasicrystals can be visualized by imagining a tiled floor," said according to a statement by Princeton University in a press release. "Tiles that are six-sided hexagons can fit neatly against each other to cover the entire floor. But five-sided pentagons or 10-sided decagons laid next to each will result in gaps between tiles." [Fallen Stars: A Gallery of Famous Meteorites]

This quasicrystal, which has not yet been named, is the second ever found in nature and the first natural decagonal quasicrystal ever found. "When we say decagonal, we mean that you can rotate the sample by one-10th the way around a circle around a certain direction and the atomic arrangement looks the same as before," lead researcher Paul Steinhardt, a Princeton University physicist, told Live Science in an email. "So, each layer has this 10-fold symmetry and then the layers are stacked with equal spacing."

The first natural quasicrystal formed outside of the laboratory, reported by Steinhardt and his colleagues in 2009, is patterned somewhat like a soccer ball, which sports 12 pentagons. "If you rotate about any of these pentagons one-fifth of the way around the circle, it gives you back a pattern identical to the original," Steinhardt said, adding that "there is not equal spacing along any direction." That quasicrystal, called an icosahedrite and made up of metallic copper, aluminum and iron, was confirmed as natural after the research team traveled to the region in 2011 to pick up and analyze additional samples.

Both known quasicrystals originated in the same meteorite collected several years ago in the Koryak Mountains in Chukkotka, Russia, though the new one was embedded in a different grain within that meteorite. In addition, this newfound quasicrystal is made up of nickel, aluminum and iron — an unusual structure in nature, because aluminum binds to oxygen and prevents attachments to nickel and iron atoms.

Now that a second one has been discovered, the researchers are intrigued as to how the quasicrystals could form in a 4.57-billion-year-old meteorite that is about the same age as Earth's solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The formation of this quasicrystal happens to be linked to the formation of one of the first meteorites to have formed in the solar system. It is telling us that exotic minerals could exist back then, well before there was an Earth and well before most types of minerals we know," Steinhardt wrote. "They would be part of the building blocks of the solar system, including planets and asteroids. Yet, we did not know before now that these quasicrystals were part of that story and we do not understand yet how they formed."

Figuring out how they formed may give scientists insight into "novel processes in the early stages of the solar system that influenced the formation of planets, including the Earth," he added.

The results were published online March 13 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus