Melting, Not Meteorite, Caused East Antarctica Crater

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

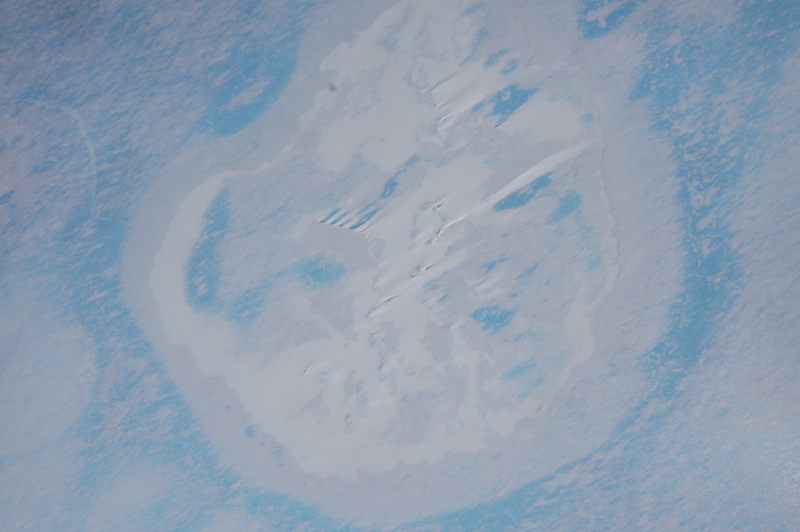

A mysterious crater that was discovered in East Antarctica last month likely formed beneath a leaky meltwater lake, rather than because of a meteorite impact, researchers now think.

The ring of sunken ice, nearly 2 miles (3 kilometers) wide, was spotted a few days before Christmas on the Roi Baudoin Ice Shelf in East Antarctica, north of Belgium's Princess Elisabeth research station. At first, German researchers suspected a meteorite blasted out the crater, because a space rock exploded over East Antarctica in 2004.

However, after the find was announced in early January, scientists gathered on social media and immediately shot down the meteorite hunch. "It was like a virtual coffee table conversation," Olaf Eisen, a glaciologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, said of the online discussion. "Real coffee table conversations are difficult for glaciologists, because there aren't that many of us and we're spread all over the world. In this case, social media was the solution," he told Live Science. [Video: Mystery Antarctic 'Crater' Could Be House-Sized Meteor Blast]

Even though only one tantalizing photo of the crater was published, Antarctica experts rapidly hunted down the circular structure on satellite images. The puzzler drew luminaries such as Doug MacAyeal, president of the International Glaciological Society, and Ted Scambos, a leading expert on Antarctic ice shelves. Within days, scientists on Facebook and Twitter had settled on an alternative origin. (The Alfred Wegener Institute recently provided clearer pictures of the icy ring.)

Glaciologists who pored over the newly discovered feature think the crater resembles an ice doline — a sinkhole-type pit that appears when meltwater lakes suddenly drain from their bottoms. The collapsed circles of ice commonly appear in West Antarctica and Greenland, where prodigious surface melting results in scores of lakes, but ice dolines aren't widely known even among glaciologists.

"Doline is a pretty obscure term," said Allen Pope, a glaciologist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado, and the University of Washington's Polar Science Center.

Historical satellite images uncovered by Pope and others suggest the ice doline crater has been traveling with the ice shelf since the 1990s. (An ice shelf is a thick, floating slab of ice anchored to glaciers or ice sheets on land.) And it's not alone — several small craters pit the surrounding ice, which suggests widespread surface melting.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The hypothesis is appealing to the scientists who found the structure, even though none had heard of ice dolines before, said Graeme Eagles, one of the German geophysicists who was at Princess Elisabeth research station during the discovery. "One of the things I learned as a geology student was that the vast majority of circular structures in rocks are attributable to processes other than meteorite impacts," he said in the station's research blog.

For researchers, the ice dolines may prove more exciting than a meteorite crater because now they must ponder how the meltwater lakes formed.

“It is still a spectacular discovery, and now it needs an explanation," said Peter Kuipers Munneke, a glaciologist at Swansea University in the United Kingdom.

Cold and dry East Antarctica isn't known for extensive surface melting, such as the lakes typically seen on West Antarctica's ice shelves. Yet the scattered ice dolines suggest there is enough meltwater to fill several lakes, Munneke said. "Maybe that's the biggest surprise," he told Live Science.

The first clear answers could arrive later this year. Alfred Wegener Institute scientists collected radar data at the crater in December, which could determine whether the structure is truly an ice doline. Analyzing the data will take several months, Eisen said. And Belgian glaciologist Jan Lenaerts, of Utrecht University, intends to visit the crater next year during an already-planned research trip to track melting on East Antarctica's ice shelves.

"The neat part of the story is that we're showing people the exploratory and discovery process of science," Pope said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus