Blobs Inside Earth Like Peanut Butter

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

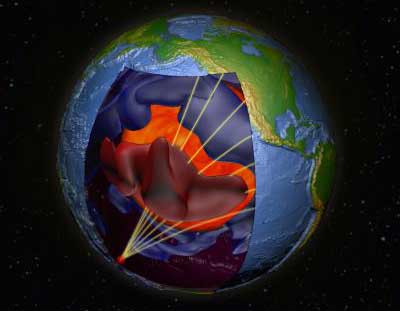

You know Earth's schematic: core, mantle, crust, right? Sorry, not so simple.

Like the gooey center of a chocolate morsel harboring peanut butter and honey, inner Earth is far more nuanced than outward appearances would suggest. A new model is proposed in the May 2 issue of the journal Science.

Earth is made up of several layers, once thought to be pretty distinct.

The skin, or crust, goes down about 25 miles (40 km). Below that is the mantle area, which extends about halfway to the center of the planet. The mantle is a thick layer of silicate rock surrounding a dense, iron-nickel core, and it is subdivided into the upper and lower mantle, extending to a depth of about 1,800 miles (2,900 km). The outer core is beneath that and extends to 3,200 miles (5,150 km) and the inner core to about 4,000 miles (6,400 km).

New data reveal the mantle consists of more varying material than was thought. So convection — how heated material bubbles up — is now thought to work differently.

"Imagine a pot of water boiling," explains researcher Allen McNamara of Arizona State University. "That would be all one kind of composition. Now dump a jar of honey into that pot of water. The honey would be convecting on its own inside the water and that's a much more complicated system."

One clue to the new thinking is that seismic waves traveling through the planet have long been measured to travel at inexplicably different speeds. Sharp speed changes suggest differing materials. On each side of the planet there are two big, chemically distinct, dense piles or blobs of material that are hundreds of kilometers thick – one beneath the Pacific and the other below the Atlantic and Africa, the researchers say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"You can picture these piles like peanut butter," McNamara said. "It is solid rock, but rock under very high pressures and temperatures becomes soft like peanut butter, so any stresses will cause it to flow."

How stuff moves within the piles should help scientists better understand how surface plates move around, causing earthquakes and building mountains.

"The piles dictate how the convective cycles happen, how the currents circulate," McNamara said. "If you don't have piles then convection will be completely different."

- 101 Amazing Earth Facts

- Will California Fall Into the Ocean?

- Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus