What Are You Really Eating? Wearable Camera Tracks Your Meals

A wearable camera that hooks around the ear could become a constant meal companion for people who want to accurately monitor their diet.

Many fitness trackers and exercise apps include a diet component, but all of them require users to self-report how much they eat. That method can lead to unreliable data, as people may forget to report some meals, poorly estimate how much they're actually eating or underreport their meals on purpose.

Currently, people can "estimate diet and nutrient intake, but the primary method is self-reporting," Edward Sazonov, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Alabama, said in a statement. Sazonov is working on a new device that aims to solve that problem. [7 Biggest Diet Myths]

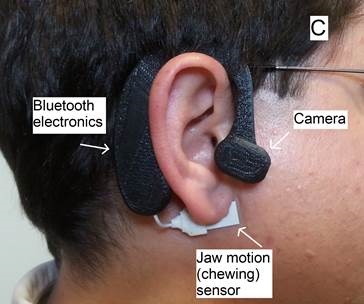

The device, called the Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM), is worn around the ear, like a Bluetooth earpiece. On the front of the AIM is a camera that can snap pictures of what you eat and drink. It also has a motion sensor that sticks to your jaw, under the earlobe, to sense movement.

The tracker ignores other jaw movements like talking and only registers chewing and swallowing. The sensor can tell the difference between talking and eating based on differences in jaw movement. The total mass and energy content of the food is calculated based on the pictures of the meals and how many times the person chewed during a meal.

"The number of chews is proportional to ingested mass and energy intake," Sazonov told Live Science in an email.

The image is analyzed by a nutritionist who identifies the food and estimates portion size, but eventually Sazonov hopes to make that process automated. A computer could calculate portion size using 3D analysis of the images.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So far, the prototype works, and Sazonov is working on developing a smaller and sleeker model for more testing.

Sazonov hopes the tracker will replace the unreliable self-reported data that many doctors and nutritionists currently rely on. He also hopes it could lead to the development of new weight-loss strategies and help researchers learn more about eating behaviors and eating disorders.

There are other high-tech diet trackers like AIM under development, including a wearable pin-on button called eButton that constantly takes pictures and uses 3D analysis to estimate the volume of food people consume.

But using a diet tracker like AIM or eButton could introduce an entirely new bias into the data, said Amy Subar, a research nutritionist at the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Control and Population Sciences division, who was not involved with the research. With a wearable device, people know their food intake is being monitored, and it's likely that awareness will influence what they choose to eat that day, Subar told Live Science.

To help avoid this bias, researchers can use the traditional self-reporting method to get more natural data. For instance, they can ask people what they ate the day before, when they weren't worried about their diet being tracked, Subar said.

Subar said there are also problems with using images to catalog the food a person is eating. Sometimes the images turn out too dark if the person is eating in a poorly lit area like a bar. It's also difficult to identify some foods based on a picture alone. For example, a picture may show that a person is eating a sandwich, but it's impossible to tell what's in the sandwich, Subar said.

Subar said new methods like AIM mark a step forward in diet analysis, but there are still many problems to work out. AIM will likely first be marketed as a medical device but could eventually become a consumer product for people who want to track their diet with more accuracy, its creators say.

Follow Kelly Dickerson on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus