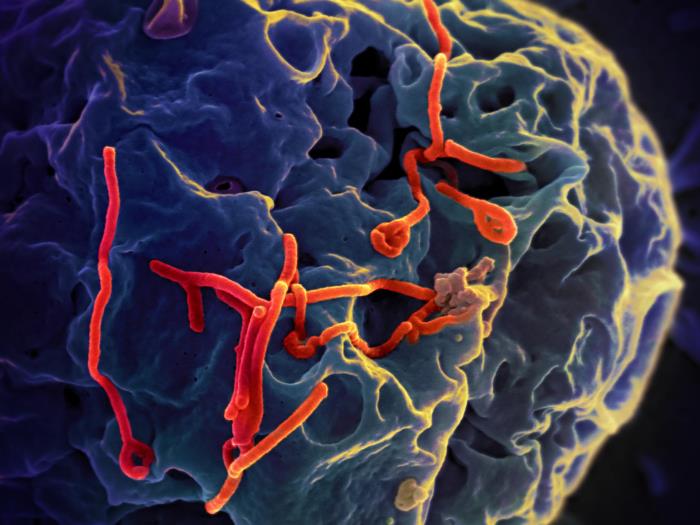

Ebola Update: No Signs of Virus Among Texas Contacts

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The people who had contact with the man with Ebola in Texas are still being monitored daily, but none have shown any sign of disease so far, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said today.

Thomas Eric Duncan is the first patient with Ebola diagnosed in the United States. He developed symptoms four days after arriving in Texas from Liberia, and is being treated in isolation at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital.

Duncan is now in critical condition, officials said. A tube has been inserted into his throat to help him breathe, and dialysis is being used to support his kidneys and rid his blood of wastes, Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the CDC, told reporters today (Oct. 7).

Health officials have identified about 50 people who had either definite or possible contact with Duncan, and all are being monitored twice a day for fever or any other sign of the disease. However, only 10 of these people are considered to be at higher risk for Ebola.

The ongoing Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone has sickened more than 7,400 people since it began in early 2014. More than 3,400 of the patients have died, according to the World Health Organization. [5 Things You Should Know About Ebola]

Duncan is being treated with brincidofovir, an experimental oral drug developed by Chimerix Inc., the hospital and the company announced Monday. The medicine was requested by Duncan's doctors, and has shown antiviral activity against five families of viruses in lab experiments.

Four U.S. health workers and an NBC News journalist who were infected with Ebola while working in West Africa were brought to the United States for treatment. Some of these patients were given the experimental drug called ZMapp, but this drug was not used to treat Duncan as the limited supplies of it have run out, Frieden previously said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Right now, there are two [experimental drugs] that we are looking at closely. [The first is] ZMapp, a combination of three different monoclonal antibodies that's promising in animal models and was used in a handful of patients," Frieden said. "As far as we understand, there's none left in the world and it takes a long time to make more." The second drug, Tekmira, has also been promising in animal models, but there are challenges in using it in people, and there's a very limited quantity of that available as well, Frieden said.

Frieden emphasized that supportive care, such as managing a patient's fluid and electrolyte balance, is critical for survival.

Ebola spreads by close contact with infected people who are showing symptoms, and does not spread through air.

"Ebola spreads by direct contact with someone who is sick or with the bodily fluids of someone who is sick or has died from it," Frieden said, adding that the virus hasn't shown any sign of becoming airborne.

"We know that most viruses don't change how they spread. To do that would require a very large genetic change," Frieden said. "The Ebola virus itself has had a great deal of genetic stability."

Samples of the virus taken in the beginning of the outbreak and those taken more recently are about 99.5 percent similar, Frieden said. "Even if we look at the virus over the past almost 50 years since it was first discovered, the rate of change is much lower than many viruses."

CDC researchers on the ground are tracking the information that could alert the scientists if the virus changes its mode of transmission, Frieden said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus