No Sympathy for the Devil: Why People Fear Satanism

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

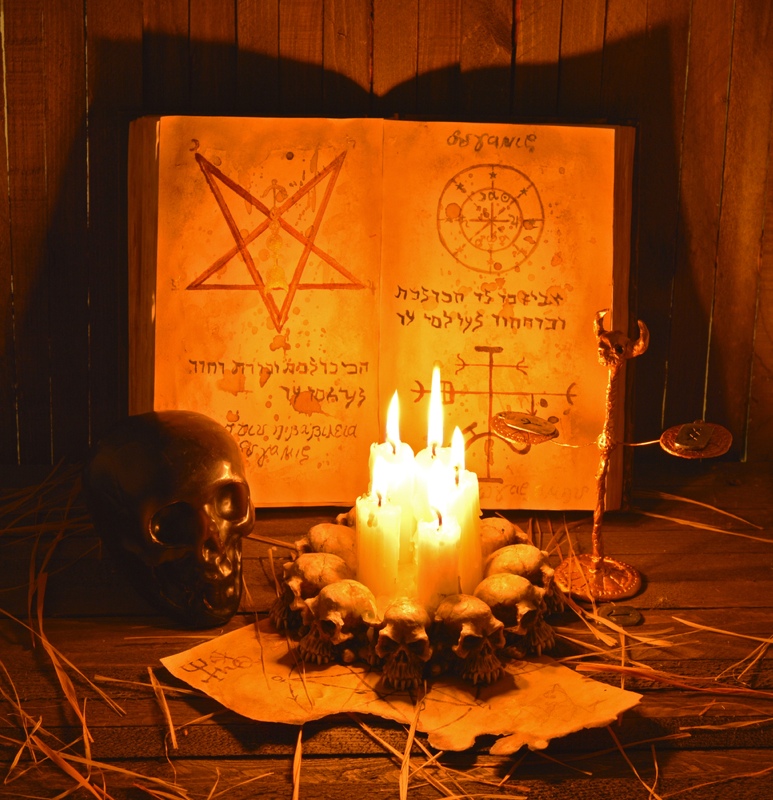

A public ceremony of Satanists planned in Oklahoma City this month has prompted protests, a lawsuit from the Catholic Church, talk of a "black mass," and even the airing of laws against bloodletting. Such public images of fear are not uncommon when it comes to Satanist groups, though they may not be justified.

The ceremony for the Oklahoma City Satanists is slated for Sept. 21 in the city's civic center and requires a ticket for admission. Officials from the city could not legally bar the group, as doing so would violate their First Amendment rights.

Officials did warn, however, that all laws must be followed, including fire codes and those involving public nudity; a spokeswoman for the parks and recreation department noted: "No bloodletting of any kind will be allowed." (Though bloodletting and animal sacrifice are popularly associated with Satanism, they have historically been part of many religions, including Christianity, Judaism and Islam.) [Tales of the Top 10 Craziest Cults]

The event has been described in the news media as a "black mass," which, as James Lewis notes in his book "Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion, Folklore, and Popular Culture" (ABC-CLIO, 2001), "refers to a blasphemous parody of a conventional [Catholic] Mass that was traditionally thought to be the central rite of Satanism." This ritual was typically said to involve perverse orgies, a torrent of various bodily fluids, obscene gestures and even "a black candle made from the fat of unbaptized babies," Lewis wrote.

Rumors of satanic black masses have horrified — and spread fear among — the pious for centuries. According to Lewis, however, "it is unlikely that such rituals were anything more than the literary inventions of church authorities" designed to demonize heretics and non-Christians.

The satanic group, Dakhma of Angra Mainyu, is using the event to make a point about freedom of religion and to educate people about their beliefs, according to news reports. "One of the dictates of the church is not only to educate the members but to educate the public and to debunk the Hollywood-projected image of our beliefs," one of the group's co-founders, Adam Daniels, told ABC News.

Pop culture Satanism

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Satanism is widely feared and misunderstood, often confused with witchcraft or even voodoo. Some Wiccan witches, for example, worship a horned god that superficially looks like a goat-headed devil. However, the pre-Christian pagan witches did not believe in anything resembling a Christian Satan. The popular image of Satanists as sinister and bloodthirsty is largely a sensationalized fictional Hollywood creation. [Witches & Wiccans: 6 Common Misconceptions]

Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey, for example, laid out nine "Satanic sins," which include stupidity, pretentiousness, self-deceit, herd conformity, lack of perspective and counterproductive pride. Most of these are pretty noncontroversial: who doesn't agree that the world would be a better place with less stupidity, self-deceit and herd conformity? These sins tend to be seen as holding humankind back from achieving its fullest potential, and have little to do with worshipping evil forces.

According to Lewis, LaVey's influential philosophy embraced and championed "Satan as the symbol of personal freedom and individualism," drawing upon his depiction as a rebellious fallen angel in Christian theology. Satan, in this context, is seen not as a symbol of evil but as a freethinking hero who rejected a capricious, domineering ruler in favor of free will.

Folklorist Bill Eills, in his book "Raising the Devil: Satanism, New Religions, and the Media" (University Press of Kentucky, 2000), notes, "In both the U.S. and Great Britain, Satanism emerged as a pressing moral concern through a series of media-influenced rumor panics. These phenomena are brief but intense events in which rumors about a menacing person or group circulate in a community. ... Usually the phenomenon climaxes with a series of vigils or hunts, and often tails off into punitive action against some scapegoat associated with the menace."

Though the "satanic panic" peaked in the 1980s with wild and false accusations of satanic ritual abuse (in which dozens of children, led and prompted by careless psychologists and police officers, claimed to have been ritually abused by Satanists), concerns about Satanism remain with us, ranging from panic over "occult" influences of Harry Potter books to false fears connecting Halloween to satanic activity.

Religious leaders in Oklahoma are upset that the Satanists are mocking Christianity and indeed they're right; much of the modern occult movement can be seen as a reaction to, and rejection of, mainstream religions and especially Catholicism. But it's also a political statement: Where one religion has been allowed a place in public spaces such as civic centers, parks and courthouses, other, lesser-known religious organizations such as satanic churches have requested and received similar privileges.

Another group, the Satanic Temple, has fought with Oklahoma City officials for the right to place a 7-foot-tall statue of Satan near an existing Ten Commandments monument in the Oklahoma State Capital. The statue is currently being built, and lawsuits are certain if the Satanists are prevented from displaying the symbol of their worship.

It's not clear what exactly the "black mass" will involve, though the ceremony will include a woman in lingerie, blasphemous costumes, profanity, an unconsecrated host, and end with a mock exorcism, suggests the ABC News report. The proceedings will likely be heavy on theater and spectacle; the shock value of Satanists holding a ritual in Oklahoma City is worth the price of admission for many.

Benjamin Radford is deputy editor of "Skeptical Inquirer" science magazine and author of seven books including "The Martians Have Landed! A History of Media Panics and Hoaxes." His website is www.BenjaminRadford.com.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus