Military Satellites Likely Saw Missile Strike on Malaysian Airlines Flight

U.S. President Barack Obama addressed the nation today (July 18) to share what his administration knows so far about the attack on Malaysian Airlines flight MH17, an "outrage of unspeakable proportions," he said, that killed nearly 300 innocent people.

All evidence so far indicates that the commercial jet, a Boeing 777, was shot down in eastern Ukraine by a surface-to-air missile launched from an area in controlled by Russian-backed separatists, Obama said.

The president offered scant technical details to explain how the government arrived that conclusion. But it's likely that heat from the explosion was detected from space by a network of military satellites. [Declassified US Spy Satellite Photos and Designs]

Satellite systems

Since the Cold War, the U.S. Department of Defense has had a multibillion-dollar space-based system to provide early warning for intercontinental ballistic missiles.

"It is a very, very precise system that has constant coverage, especially over Russia and Ukraine," said Riki Ellison, founder of the Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance.

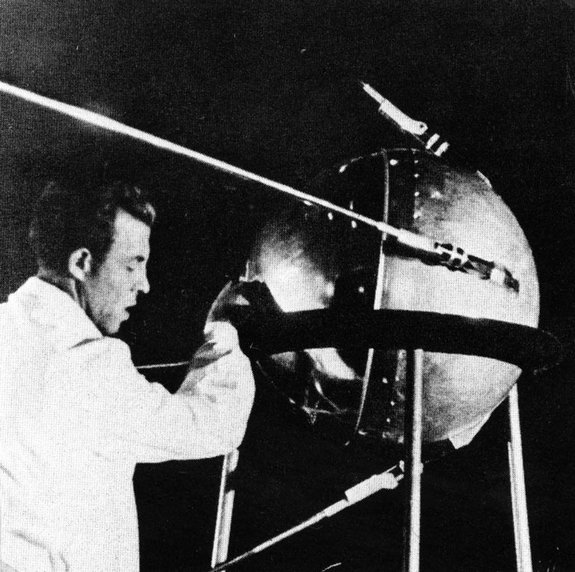

Starting in the 1970s, the Pentagon has launched a series of high-altitude satellites with Earth-facing infrared telescopes as part of its Defense Support Program, or DSP. That constellation has kept a continuous watch on the planet for the hot plumes of exhaust from missiles to warn the military and intelligence communities about possible strikes and battlefield threats.

In the past few years, DSP has undergone a major upgrade, becoming the Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS), with the launch of better satellites that can detect faint missiles faster.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

SBIRS now includes two geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO) satellites, built by Lockheed Martin, that are each hover above an unchanging spot on planet, more than 22,000 miles (35,400 kilometers) high. (For comparison, the International Space Station orbits at an average altitude of about 248 miles, or 400 km). The first of those satellites, dubbed GEO-1, launched from Cape Canaveral in May 2011. Lockheed Martin recently announced that it won a $1.86 billion Air Force contract to complete the fifth and sixth GEO satellites as part of SBIRS.

It's likely that the strike on MH17 showed up as an alarming blip on screens at Buckley Air Force Base in Colorado where those data from the SBIRS is processed. The detection is precise enough to detect where a missile was fired from and what kind of missile it was.

"Each missile has a different signature plume," Ellison said.

Ellison told Space.com that other military satellites in the region probably would have been alerted to gather further information to be provided to the U.S. European Command.

When asked if the U.S. military was increasing its surveillance of the region, Navy Rear Admiral John Kirby, the Pentagon press secretary, only said during a briefing today, "We're monitoring events as closely as we can."

The plane broke up in the air and left a miles-long trail of debris over Ukrainian farmland, with bodies, travel guides, kids' playing cards and a peacock among the charred remains, The New York Times reported. There were reports of looting soon after the crash and Kirby said he didn't know who was in possession of the plane's black box, or flight recorder. Though no Pentagon officials have been brought in to help with the international investigation, Kirby said the analysis must be "credible, transparent and unimpeded" and called for a ceasefire as the only way to ensure safe and unfettered access to the site.

While government satellite images of the crash and its aftermath might not seen by the public, commercial satellite companies might provide photos of the crash site in the days ahead.

Earth-watching satellites operated by DigitalGlobe attempted to snap photos of the crash site today, but cloud cover obscured the view, a spokesperson for the Colorado-based company told Space.com. DigitalGlobe, however, plans to continue imaging the area with its five satellites and will post the pictures it collects publicly online.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.