Wreck of Civil War Ship Commandeered by Slaves Rediscovered

The wreck of a ship once commandeered by slaves and sailed to freedom during the Civil War has very likely been found.

The shipwrecked Planter almost certainly rests beneath 10 to 15 feet (3 to 5 meters) of sand and water off Cape Romain between Charleston and Georgetown, South Carolina, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced this week. The ship went down in 1876, 14 years after its enslaved captain and crew ran it out of Charleston Harbor and turned it over to the U.S. Navy.

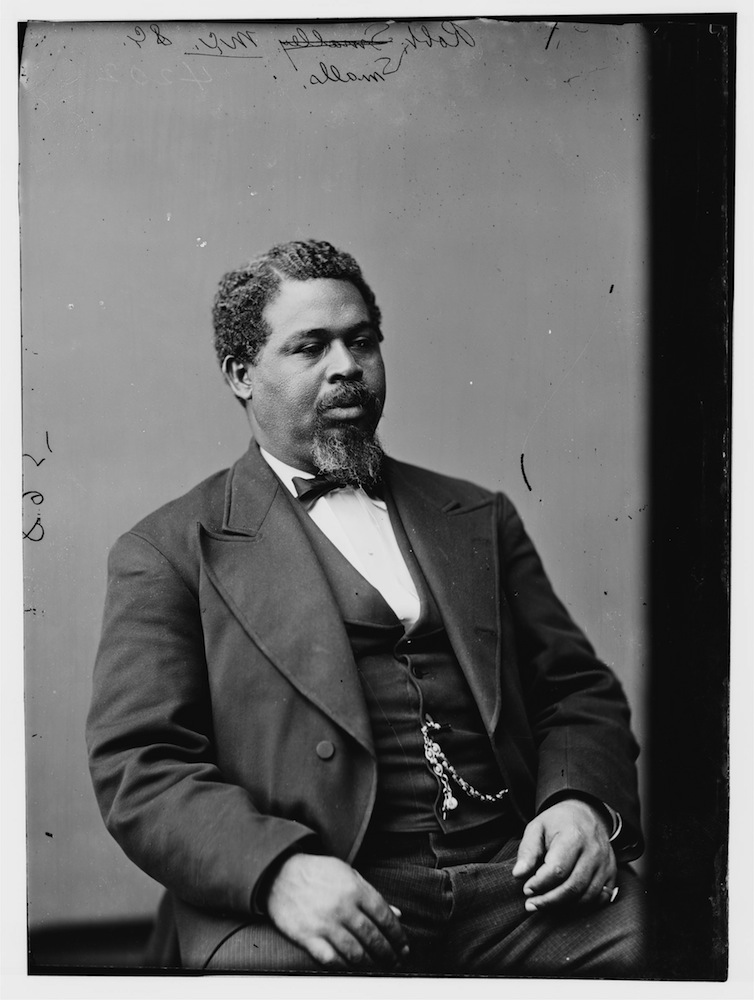

The story of the Planter is one of heroism. The ship was completed in 1860. The next year, an enslaved young man named Robert Smalls came aboard as a deck hand. Smalls had more freedom than most slaves, and was allowed to keep some of his pay and move around the Charleston waterfront with some autonomy. (Smalls may have been his owner's son, according to his descendants. Smalls' mother was a slave in the home of a man named John K. McKee, and the family suspects that McKee's son Henry, who inherited the pair of slaves in 1848, fathered Smalls.) [See Images of the Planter and Shipwreck Site]

Audacious plan

Smalls worked his way up to the position of wheelsman — the person who steers the ship. During the Civil War, the Planter was rented to the Confederates and used as a supply, transport and dispatch ship, running cannons, soldiers and other wartime necessities along the coast. Most of the crew were enslaved African-Americans.

The idea of commandeering the ship started as a joke, Smalls would later tell Harper's Weekly magazine. But soon it turned quite serious: The nine African-American men of the crew met in secret at Smalls' house and planned their escape. They put away provisions in the hold and waited for their chance.

It came on May 12, 1862. The ship had just returned to Charleston Harbor after picking up some cannons from nearby Cole Island. The plan was to deliver the weaponry to Fort Ripley the next day. That evening, however, the white men in the crew went ashore for a soiree. Smalls and his crew jumped at the opportunity, first steaming to pick up their relatives in the North Atlantic wharf and then sailing right out of the harbor. Smalls blew the ship whistle at the Confederate checkpoints, convincing those guarding the harbor that the ship was simply getting an early start on the day's deliveries.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Once out of range of the rebel guns the white flag was raised, and the Planter steamed directly for the blockading [Union] steamer Augusta," Harper's explained in June 1862.

Heroism and loss

Smalls delivered the Planter and the 16 escaped slaves on board to the U.S. Navy. He then piloted the ship in action against the Confederacy, and was later transferred to pilot other ships in a new post in the U.S. Army. He'd have another brush with heroism in 1863, again on the Planter. The ship was moving supplies along Folly Island creek near Charleston when it came under heavy shelling from Confederate guns. The captain of the ship ordered that the ship be beached and abandoned his station. Smalls instead piloted the Planter to safety. As a result, the ship's captain was dismissed, and Smalls promoted. He was the first African-American to become a ship captain in the U.S. military. [Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep]

After the war, the Army sold the ship to a private company, which turned right around and sold it to its original owner in South Carolina, John Ferguson. The ship soon went back to its pre-war duties delivering supplies up and down the South Carolina coast. Smalls went on to represent South Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In 1876, the Planter was attempting to tow a ship that had run aground at Cape Romain up the coast from Charleston. In the process, the Planter hit a shoal and sprung a leak. The captain beached the ship in hopes of repairing the hull, but a storm blew in and battered her beyond repair. The crew salvaged everything they could, including pistons, life boats, engines, cabin doors and even blankets and mattresses.

Rediscovery

Shifting sands have long covered the remains of the Planter, and the site of the wreck was lost. NOAA's Maritime Heritage Progam set out to find the wreck, reviewing original accounts of the accident and historic charts of the shoreline as it was in 1876. Once a likely location was pinpointed, NOAA researchers used a magnetometer towed beneath the water in search of large quantities of iron.

The found one such cluster 9 feet (3 m) below the ocean bottom, near where the shore would have been when the Planter wrecked. The area is environmentally sensitive (Cape Romain, up the coast from Charleston, is home to a national wildlife refuge), so attempts to uncover the wreck will need to be taken with care, NOAA reported. What's more, the Planter is likely fragmented from the relentless beating of the waves. The state of South Carolina will decide whether to excavate the ship's remains or to simply mark the spot in remembrance of this storied vessel.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.