Ancient Sheep Poop Reveals Desert Island's Secret Past

On the floor of a cave in a remote desert island in Mexico, scientists stumbled across a mat of urine-hardened poop, dating back to more than 1,500 years ago. The fossilized dung offers surprising evidence that bighorn sheep once lived on the uninhabited island, a new study claims.

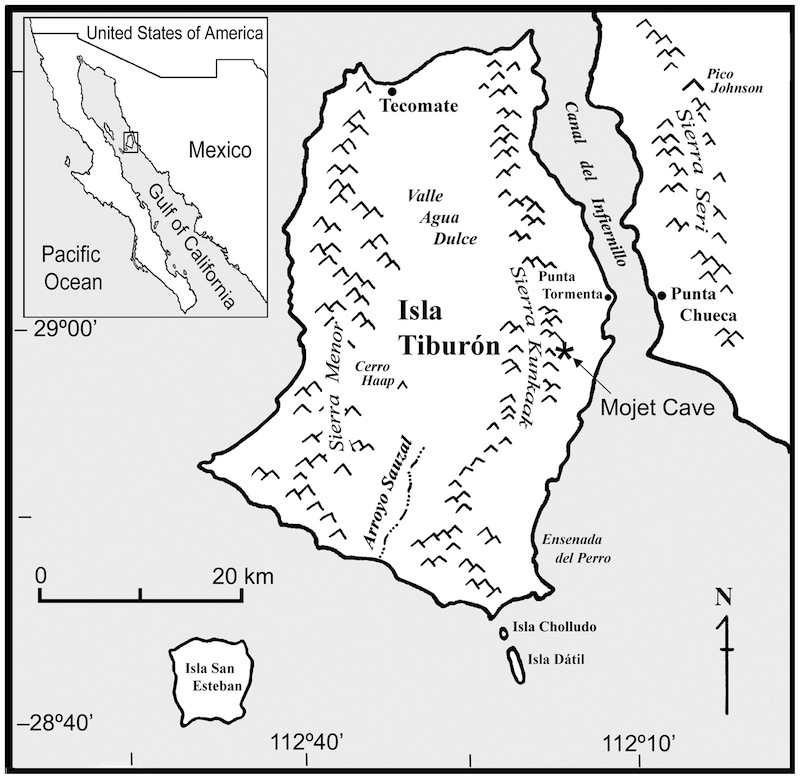

Around 500 bighorn sheep can be found on Tiburón Island in the Gulf of California today — but that population descends from a group of animals brought there by conservationists in 1975.

Starting with 16 females and 4 males, conservationists established a population of bighorn sheep to bolster the species' numbers on the mainland. Tiburón Island was chosen because it had little hunting and few human disturbances. It also lacked big predators like mountain lion and disease-transmitting animals like domestic sheep. [6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life]

The fossilized poop was found in a cave in the Sierra Kunkaak mountain range of the eastern side of the island while scientists were looking for the traces of ancient woodrats.

Researchers took DNA samples from the dung and compared it with poop from both living and extinct herbivores, matching it with the feces of modern desert bighorn sheep. (The size and shape of the poop pellets apparently also matched.)

"It's a very clear result," study researcher Clinton Epps, a conservation geneticist at Oregon State University, said in a statement. "Furthermore, the sequences are not identical to the modern bighorn populations on Tiburón Island — so we are confident that the sequences do not derive from modern use of the cave by introduced bighorn sheep."

With just one sample of fossilized poop, it's not clear when exactly bighorn sheep lived on the island, or if they lived there for a continuous period or repeatedly colonized the place. While the researchers say they can't pin down when or why the animals became locally extinct during the past 1,500 years, they have a few suspicions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We hypothesize that isolation of the prehistoric Tiburón bighorn sheep population resulting from sea level rise, combined with subsequent drivers that act on small populations, including inbreeding, overharvesting by hunters, and megadroughts typical of Northern Mexico and the Southwestern U.S.A., figured in their local extinction," the researchers, led by Ben Wilder, of the University of California, Riverside, wrote in their paper.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.