If you had held out some hope that the universe's first few moments would be easy to understand or visualize, consider your bubble officially burst.

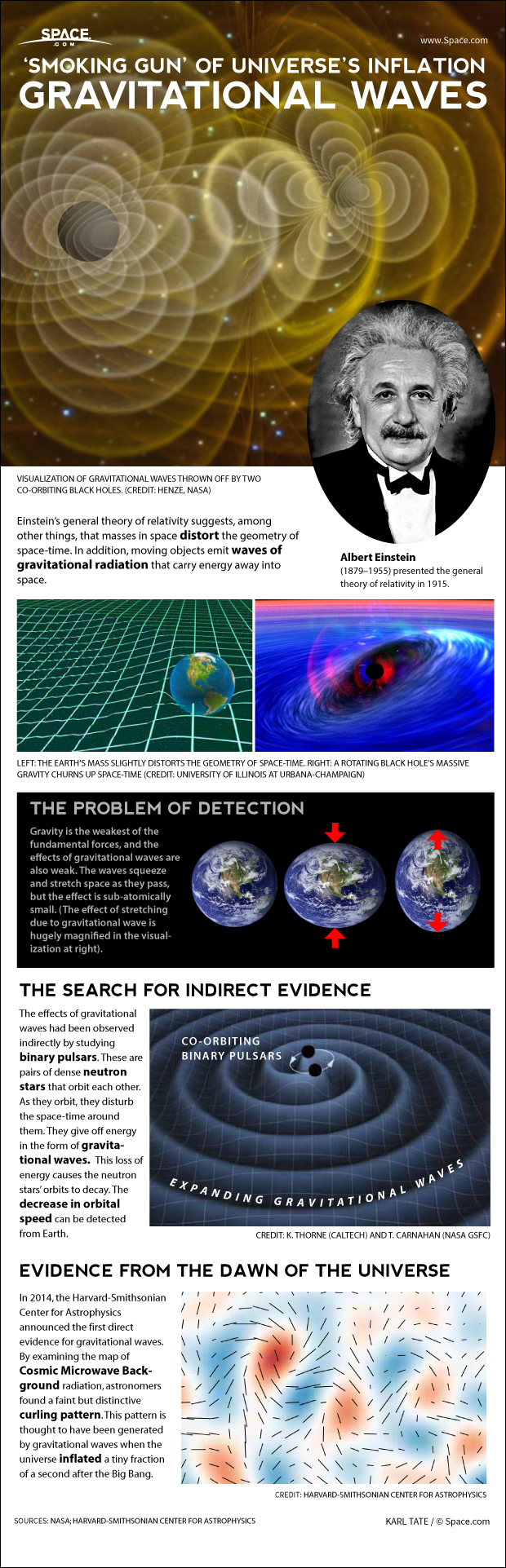

Astronomers announced Monday (March 17) that they have discovered a telltale signature of gravitational waves in the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB), the light left over from the universe's birth 13.8 billion years ago.

The new results suggest that space-time really did expand at many times the speed of light in the first few tiny fractions of a second after the Big Bang, as predicted by the theory of cosmic inflation, researchers say. [How Inflation Gave the Universe the Ultimate Kickstart (Infographic)]

That may seem impossible, since Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity holds that nothing can travel faster than light. That rule, however, applies only to matter and information moving through space, not to the expansion of space-time itself.

If that's not mind-blowing enough, here's something else: During the inflationary epoch, three of the universe's four fundamental forces — all of them except gravity — probably blended together.

"The scale at which we have detected a signal corresponds to what has long been understood to be the predicted energy scale at which grand unified theories operate, and unify the strong, the weak and the electromagnetic force all together," study leader John Kovac, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Space.com.

That energy scale is around 10^16 billion electron volts, or roughly 1 trillion times greater than the levels achieved by Earth's most powerful particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider, said Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb, who is not a member of the study team.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We have no chance of probing that scale in the laboratory," Loeb told Space.com.

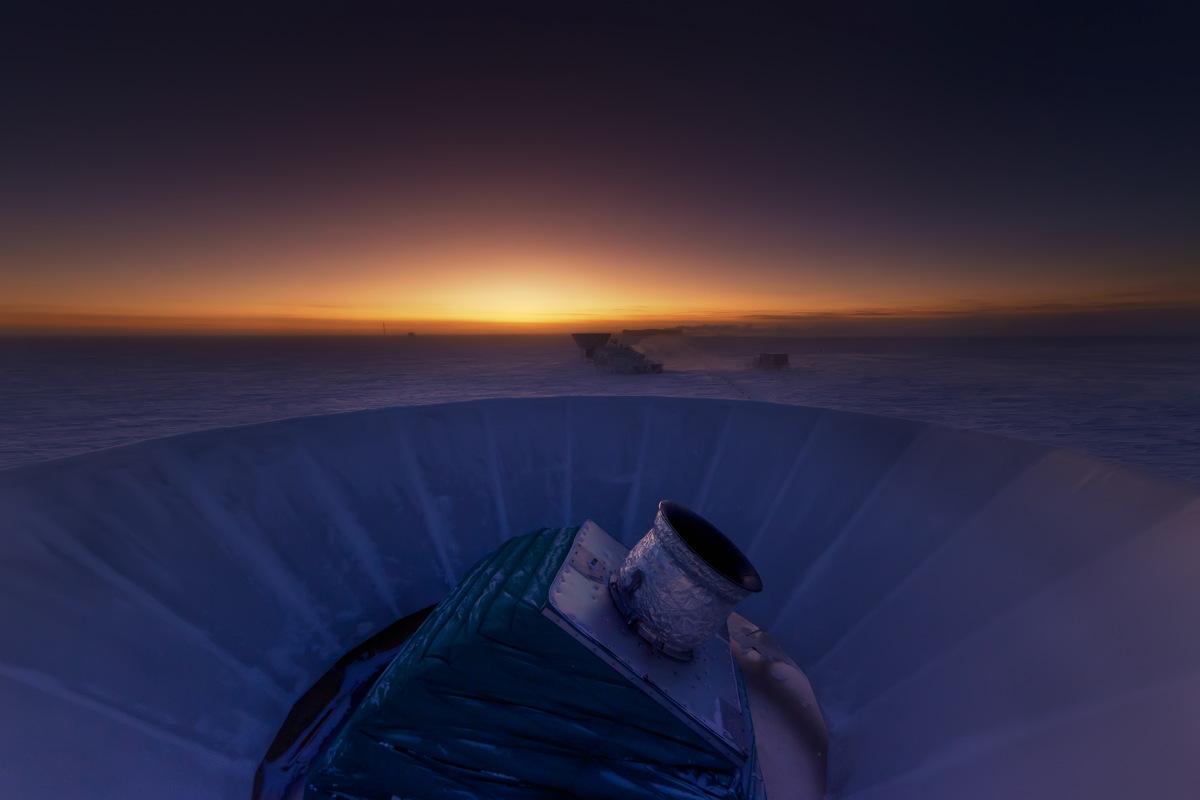

The new study, conducted using the BICEP2 telescope in Antartica, found characteristic swirls in the polarization pattern of the CMB. These swirls could only be produced by primordial gravitational waves — whose existence was proposed by Einstein in 1916 as part of his theory of general relativity — just after the Big Bang, study team members said.

The potential discovery will only be fully accepted if other research teams confirm it using different instruments, Loeb said. But the basics of inflation theory appear to be on pretty solid ground — and they can be hard for even professional cosmologists to wrap their heads around.

"To me, it's quite amazing that you can start from entities that are described by quantum mechanics and end up, through this enormous expansion that the universe has at the time of inflation, with objects that are very dear to us as classical objects — such as the Milky Way galaxy, inside of which you have stars like the sun, around which you have planets like the Earth," Loeb said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.