Tectonic Puzzle: Why West Africa Didn't Follow South America

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

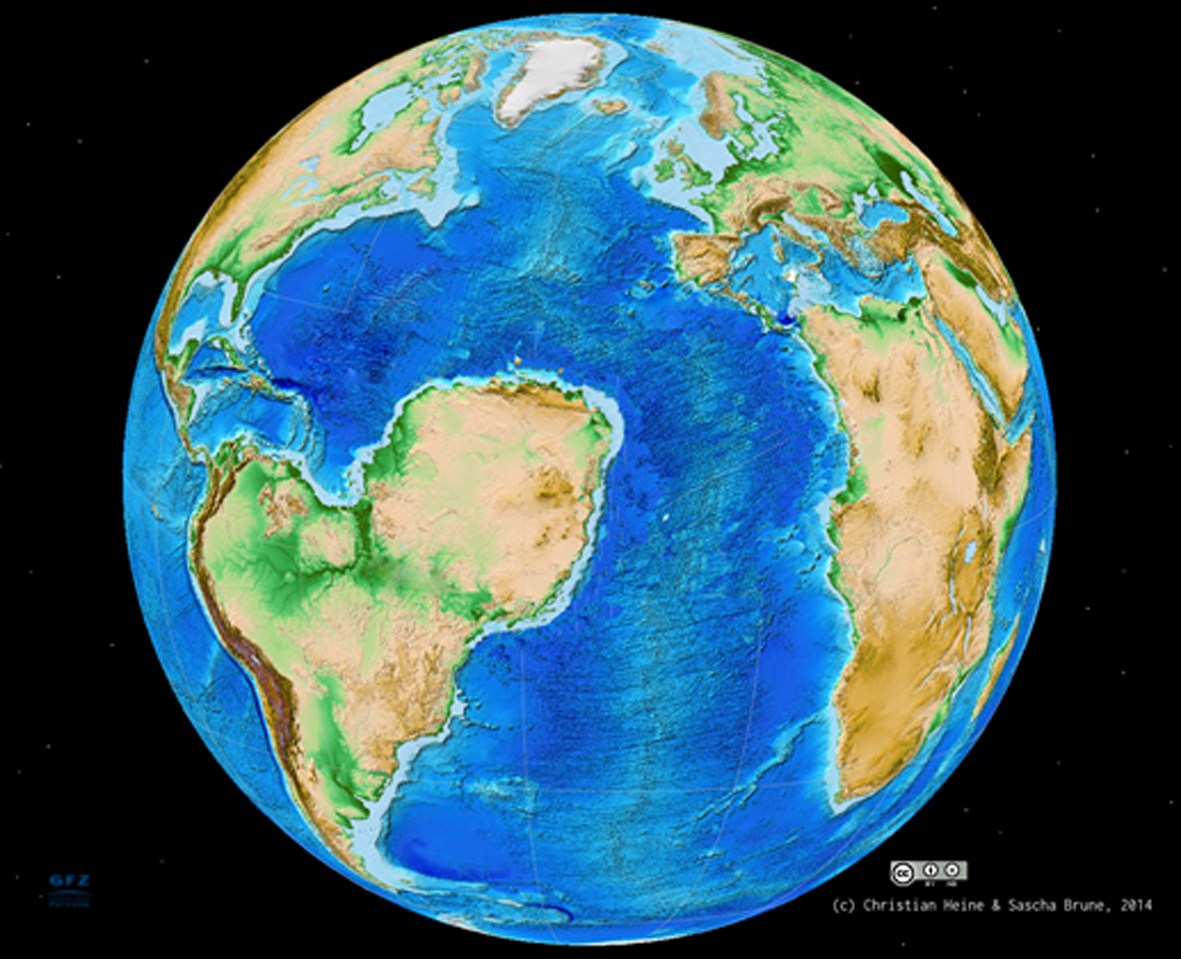

South America nearly carried off Northwest Africa when the world's last supercontinent fell apart 130 million years ago. Now, a new model helps explain why the Sahara settled east of the Atlantic instead of sailing off with South America — it's all about the angles.

Back before the Atlantic Ocean formed, Africa and South America nestled together in a massive supercontinent called Gondwana. When this landmass started to split, gashes in Earth's crust called rifts opened up along pre-existing weaknesses.

One of these gashes, called the West Africa Rift System, started to tear apart the future Sahara desert. Two more rifts formed along the future boundaries of South America and Africa. Imagine three rift zones, two lined up essentially north-south and one pointing east-west. These alignments are key to explaining why the continents broke apart the way they did, according to a study published March 6 in the journal Geology.

The planet's plate tectonic forces could more easily pull apart the two continents at the east-west–oriented rift than at the north-south–oriented rift in the Sahara desert, the researchers found.

"The direction in which the continents break apart heavily influences the success of the rift system," said study co-author Sascha Brune, a geophysicist at GFZ Potsdam in Germany. "Because the rift system was at a very low angle to the extension direction, this rift won out in the end," he told Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

At that time, South America was heading westward. "Plates are pulled apart by large-scale geological forces that come from the plate boundary or the mantle, but for the rift, it's not important where these forces come from," Brune said. "If you pull more in the direction of the rift, you need two times less force to get the rift going." The mantle is the hotter layer of rock beneath Earth's crust.

The crust often breaks apart at three-pronged junctions, such as the triple rift that formed between Africa-South America, and it's not uncommon for one rift to fail to develop. The model developed by Brune and his co-authors suggests that the angle between the rift and the plate tectonic forces plays an important role in determining which rifts will fail.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus