Female Mice Choose Mates That Don't Sing Like Dad

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

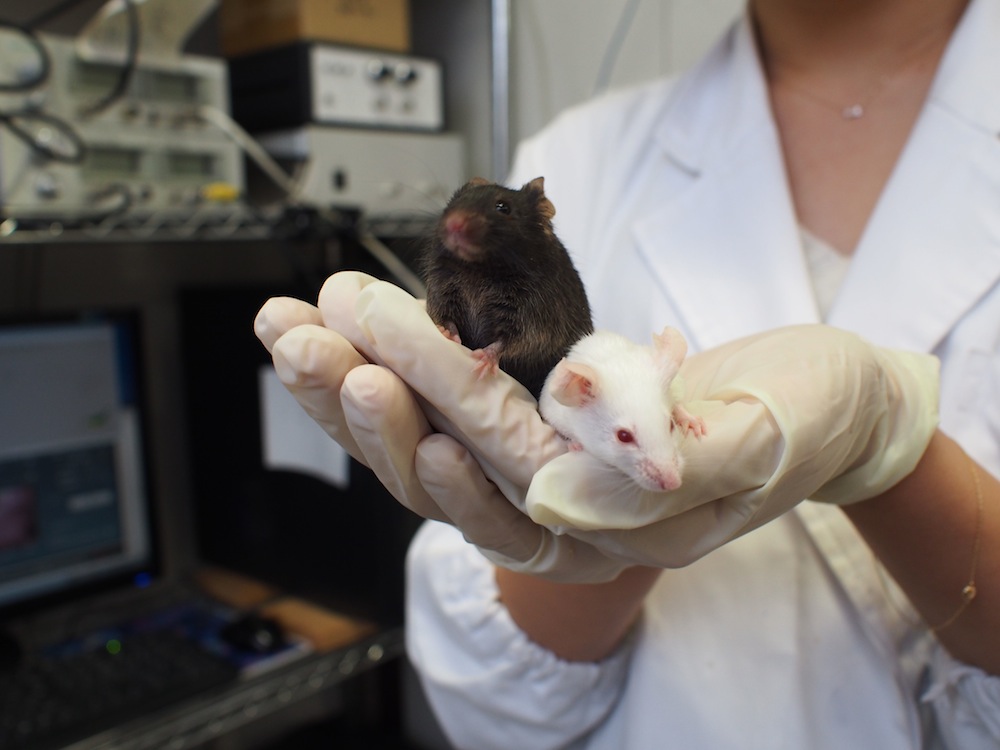

When selecting a mate, female mice choose males with songs that differ from those of their parents to avoid inbreeding, a new study finds.

To woo females, male mice sing songs, or produce ultrasonic vocalizations, that are too high-pitched for humans to hear.

Females remember their fathers' songs from a young age, and avoid mating with mice that sound similar and may be closely related to them, according to the study detailed online today (Feb. 5) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Animals often learn at a young age what characteristics make a desirable mate, a process called sexual imprinting. Mating with relatives can result in offspring with harmful or life-threatening genetic conditions, so mice and other animals must learn to recognize close relatives and avoid hooking up with them. [Top 10 Swingers of the Animal Kingdom]

In the study, the researchers raised female mice with either their biological father, an unrelated father or no father at all. The scientists recorded songs from four male mice, including one that was closely related to the females.

The researchers placed the female mice in a cage with chambers where they heard the males' songs and smelled the males' sexual scents. They recorded how long each female spent in each chamber before choosing a chamber (and a mate).

The female mice raised with their biological father spent most of their time in rooms playing the songs of males that were unrelated to them, the researchers found. Likewise, females raised with a non-biological father preferred chambers that played songs from mice unrelated to the non-biological father. Females raised without a father showed no preference between songs of relatives and those of strangers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings suggest that female mice can distinguish among male songs and prefer songs of mice unrelated to them. The females may learn to make these distinctions based on early life experience, rather than genetics, the researchers said.

The study may be one of the first in mammals to show the use of male songs to recognize kin in order to prevent inbreeding.

But songs aren't the only signals mice use to interact with the opposite sex. Mice also rely heavily on their sense of smell. They are known to favor mates whose odor indicates components of their immune system are unlike their own; mating with these mice results in offspring more likely to survive and reproduce.

In the song study, the female reproductive cycle and male sexual scents also influenced the females' preference for different chambers, but life experience was the most important factor in how they made their choices.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus