The Astronomy of Halloween

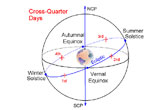

Halloween means more than just a day for costumes and candy corn. It's the halfway point between the autumnal equinox and winter solstice, the last of four "cross-quarter" days on the solar calendar.

"Our recognition of the cross-quarter days in the English-speaking world comes primarily from the Celts who lived in Britain in pre-Christian times," said astronomer Richard Pogge at Ohio State University.

Unlike us, Celts, as well as traditional Japanese Shinto societies, considered equinoxes and solstices the middle of a season. They chose cross-quarter dates as a time to ring in the beginning of each season.

Regardless of when you say a season begins or ends, equinoxes, solstices, and cross-quarter days [image] observe shifts in sunlight.

On the equinoxes, the sun rises and sets due east and west, respectively. During the summer solstices, the sun rises the furthest to the northeast and sets furthest in the northwest, whereas in winter it rises the furthest southeast and sets in the southwest.

Cross-quarter days mark the midway spot of the sun's apparent path as the Earth orbits around the sun.

Although the astronomical ties have largely been forgotten, each cross-quarter day has a matching minor holiday that dates back to the Celts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When the Celtic peoples were converted to Christianity, they kept their festivals but renamed them to conform to Christian practice," Pogge said.

Today we commemorate cross-quarter days with the holidays Groundhog Day, May Day, and Lammas Day—a less well-known harvest holiday celebrated on August 1— and Halloween. The actual fourth cross-quarter day ranges from Nov. 5-8, yet for simplicity's sake Halloween has been fixed on our calendars as Oct. 31.

Celts called the day Samhain, or "summer's end." The day was also their New Year's Eve. But they weren't the only ones celebrating the skies.

"Many cultures watched the solar motions," Pogge told LiveScience. "For example, the pre-Columbian Native American city of Cahokia outside of St. Louis had a wood-stake solar observatory—called the woodhenge—that marked annual solar motions."

Stonehenge in England and ancient Mayan sites in Central America show similar solar alignments and observatories.

This article is part of LiveScience's weekly Mystery Monday series.

Full Frightening Coverage

- What Halloween is Really About

- The Shady Science of Ghost Hunting

- Halloween's Top 10 Scary Creatures

- Higher Education Fuels Stronger Belief in Ghosts

- Vampires a Mathematical Impossibility, Scientist Says

- Candy Fears are Mere Halloween Phantoms

- Halloween Too Scary for Some Kids

- In Search of the Real Dracula