Adopt a Skull to Save Cranium Collection

Looking for the perfect holiday gift for a slightly morbid loved one? Adopt a skull for them.

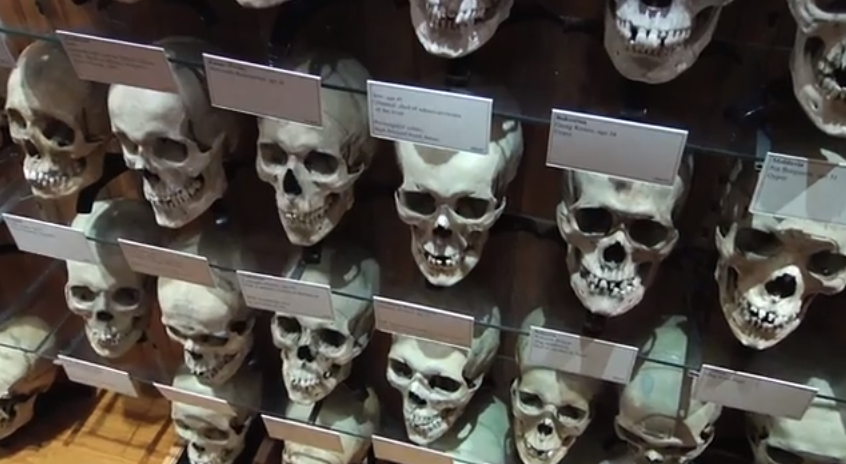

The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia's Save Our Skulls fundraiser is inviting fans of medical history and the macabre to step up and donate to help restore a collection of skulls dating back more than 150 years. For $200, a person can adopt the skull of their choice. Besides bragging rights, the donation gets the adopter's name on a plaque next to the repaired and remounted skull.

The skulls (there are 139) belonged to Josef Hyrtl, a 19th-century Austrian anatomist. Hyrtl collected the skulls to disprove the science of phrenology, which held that a person's personality and character were reflected in the size and shape of their skull. Phrenology was nothing but pseudoscience, but it was held in high esteem in the 1800s.

"As a devout Catholic, Hyrtl did not subscribe to the phrenologists' idea that the human brain was subject to changes that could be seen in the measurements of the skull," wrote Seton Hall University graduate student Sara Keckeisen in a 2012 master's thesis about the skull collection. "Hyrtl saw comparative anatomy, not phrenology, as the path to knowing God's true plan through science." [Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal With The Dead]

Cranium collection

Most of the skulls belong to criminals who were executed, people who committed suicide, or people institutionalized because of disabilities — typical anatomical research subjects in those days. It was an illegal yet secretly accepted practice for Hyrtl and other anatomists to pay grave robbers to bring bodies to them; and criminals, paupers, the mentally ill and similarly disenfranchised populations rarely had families who would object to a disturbed grave. However, Keckeisen wrote, Hyrtl's collection comes with biographical information on many of the skulls' owners, suggesting that rather than to rob graves, he paid off hospital and prison officials to pass him bodies directly.

The collection contains skulls from people between ages 8 and 80. Fourteen belonged to women. Most are Eastern European or Asian. Although not part of the Mütter Museum's collection, the skull of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is said to have once belonged to Hyrtl.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Upon his retirement, Hyrtl began to sell his anatomical collection. The Mütter Museum acquired the 139 skulls in 1874. They were used to train medical students and later displayed as the museum's mission changed from solely medical education to public outreach. In 2008, the skulls were scanned with computed tomography for further study.

Tragic tales

The skulls tell tales of life on the margins of 1800s society. One skull marked by defective tooth enamel belonged to Franz Braun, age 13, who hanged himself after he was caught stealing. One of the women in the collection, a maidservant named Maria Falkensteiner, died of meningitis, an infection of the tissue surrounding the brain. Another maidservant, Magdal Pagrac, died of childbed fever (an infection contracted during childbirth). A third woman was executed for the murder of her own child.

Many of the skulls belonged to the young. A 28-year-old Hungarian soldier named Joska Soltesz died of pneumonia. Typhus took both 21-year-old Koloman Ergetty and 25-year-old Joh Samek. Gregor Sipnik, 15, died of tuberculosis. Smallpox killed 15-year-old Czech shoemaker Wenzeslaus Kral.

Some of the tales are strange. Geza Uirmeny, 80, tried to commit suicide by cutting his own throat at age 70. He survived and "lived until 80 without melancholy." A robber in Lebanon died by "deheading." Other descriptions of skull origins are terse or missing altogether; several skulls are identified only as belonging to an "idiot" or "cretin," which were both medical terms denoting intellectual disability at the time. Mirju Aslan, 18, of Romania is described only as a "child murderer."

The Save Our Skulls initiative continues through Dec. 31, 2013.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.