Venice's Gradual Sinking Charted by Satellites

Venice, the "floating city" of romance and gondolas, is slowly sinking into its watery foundations.

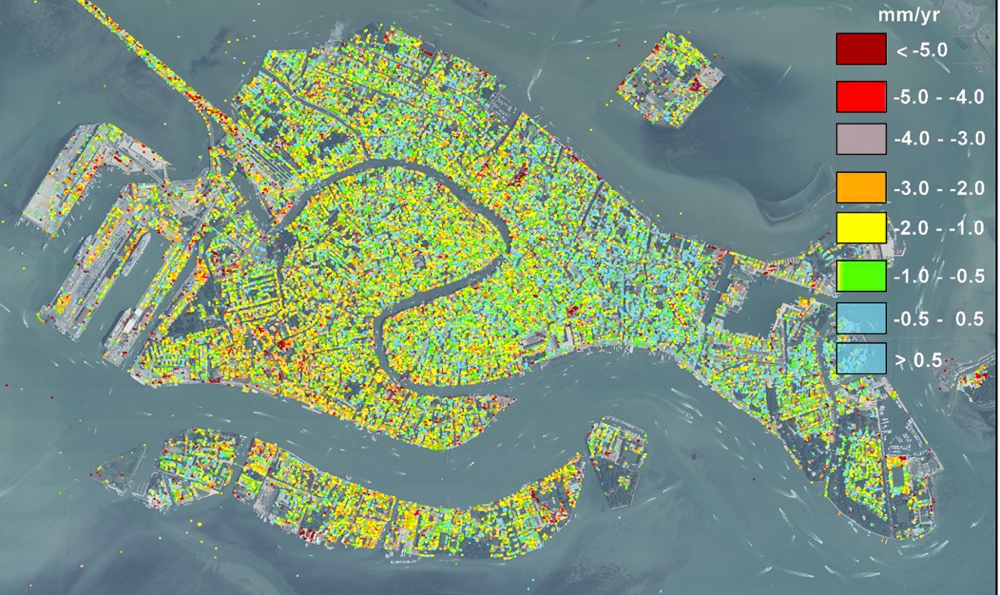

A new study using modern satellite data has shown the amount that Venice is sinking with an unprecedented level of resolution, allowing scientists to tease apart the influence of natural causes of the sinking, due to compaction of the sediments on which the city is built, versus man-made ones, such as building restoration.

Understanding how the land is sinking is particularly important in the face of rising sea levels. "Venice is in a situation so critical with respect to the sea that continuous monitoring of the city's movement is of paramount importance," said study researcher Pietro Teatini, a hydraulic engineer at the University of Padua in Italy. [8 Ways Global Warming is Already Changing the World]

Scientists first recognized the problem decades ago when they noticed that pumping of groundwater from beneath Venice was causing the city to settle into the earth. The pumping and its effects have long since stopped, but the city continues to sink.

In the study, Teatini and his colleagues used two sets of satellite measurements of Venice's historical city center and the surrounding area. The first dataset came from first-generation satellite sensors that have coarse resolution and collect data about once a month, whereas the second dataset comes from a newer satellite with sensors that have much better resolution and take measurements every 10 days.

"The techniques are continuously evolving and improving, and we are able to detect displacement with an accuracy that was unbelievable 10 to 20 years ago," Teatini told LiveScience.

The satellites beam signals down to the Earth's surface, where they reflect off land and buildings. To determine the amount that Venice is sinking, the researchers measured differences in the signals returning from the city relative to those returning from nearby areas, a method called interferometry.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Teatini's team compared short-term changes in the city's height measured by the new satellite from 2008 to 2011 with the average, long-term movement measured by the old satellite from 1992 to 2010. Then they subtracted the short-term changes in ground level from the long-term ones to determine the human contribution to the sinking.

The results revealed the city is naturally subsiding at a rate of about 0.03 to 0.04 inches (0.8 to 1 millimeter) per year, while human activities contribute sinking of about 0.08 to 0.39 inches (2 to 10 mm) per year. However, human activities, such as conservation and reconstruction of buildings, cause sinking only on a localized, short-term scale, the researchers said.

The sinking threatens to increase flooding in Venice, which already occurs due to high tides about four times per year. And the problems are compounded by rising sea levels resulting from climate change. The Northern Adriatic Sea is rising at about 0.04 inches (1 mm) per year, Teatini said. To buffer this rise, the MOSE (Experimental Electromechanical Module) project, planned to begin in 2016, will install a system of movable gates that would block the inlets to the Venetian lagoon during high tides.

Teatini and his colleagues' study was detailed today (Sept. 26) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Venice isn't the only city that's sinking – parts of New Orleans are dropping at a rate of 1 inch, or 2.5 cm, per year, possibly due to the removal of oil, gas and water from underground reservoirs, studies suggest.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.