Scorpion Is Gondwana's Oldest Land Animal

A fierce predator with a huge stinger and long pincers is the oldest land-animal fossil ever found on the former Gondwana supercontinent, a new study reports.

The 360-million-year-old scorpion was discovered in a spectacular fossil deposit in South Africa at Waterloo Farm, near Grahamstown. Until now, the only evidence of ancient creepy crawlies on land came from Laurasia, the giant land mass north of Gondwana.

The fossil confirms that invertebrate animals, such as scorpions, colonized both Gondwana and Laurasia during the Devonian period. At the time, the two supercontinents were separated by the Tethys Ocean. Researchers had spotted the same trees and plants, as well as similar fish, on both supercontinents, but scorpions and other land-living animals were confined to Laurasia.

The discovery also extends the range of ancient land animals. Parts of Gondwana crossed the South Pole in the Late Devonian (Earth's climate was warmer than it is now), while most of Laurasia rested in the warmer tropics. The shallow sea where the scorpion bits were buried and preserved in black mud sat at 80 degrees South latitude. [Have There Always Been Continents?]

"What we're seeing is the Late Devonian ecosystem was not just along the tropical belt, but also extending to the high latitudes. [This] is quite important, because this is actually the environment in which early tetrapods are thought to have emerged around the latest Devonian," said Robert Gess, a paleontologist at Wits University in South Africa, who discovered the scorpion fossil.

Tetrapods were the first vertebrates to walk on land. Scorpions, millipedes and insects were their likely food source, Gess said. "The conditions for when these creatures first emerged were global," he told LiveScience. "That's quite a big piece of evidence."

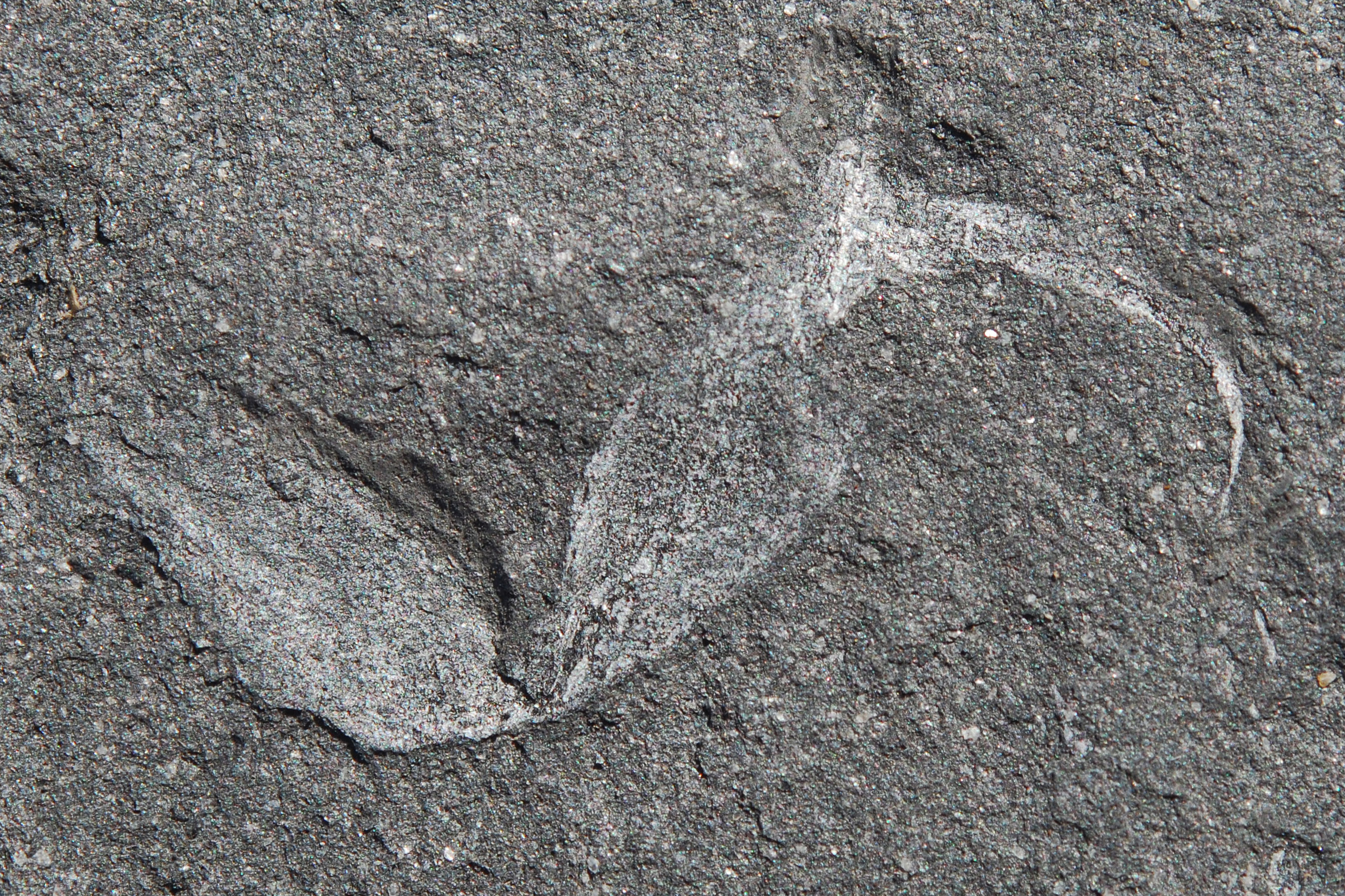

Only two parts of the newly discovered scorpion — a pincer and a tail — were recovered from the black shale at Waterloo Farm. The entire creature was probably 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 centimeters) long, Gess said. The black shale formed from layers of shallow sea mud, but the fossil diversity and preservation are similar to those found in Canada's famous Burgess Shale, a deep-sea environment that offers a window into Early Cambrian life, Gess said. The Cambrian period, which lasted from 543 million to 490 million years ago, marks the dramatic evolutionary expansion of life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We haven't even finished the excavations, but once we're done, this will be one of the milestone sites of the Late Devonian," Gess said.

Waterloo Farm was discovered during highway construction in 1985. The site has also yielded fossilized fish, plants and the world's oldest lamprey, a jawless fish with a circular, toothy mouth.

Gess believes more Gondwana land animals are waiting to be discovered, both at Waterloo Farm and in the scattered supercontinent remnants — Africa, South America, India, Madagascar and South America.

"There's a long history of paleontology in Europe and North America, whereas in places like Africa and South America, it hasn't been as big as a field," Gess said. "I think we will be finding a lot of the missing stuff [in the future]," he said.

The findings were published Aug. 28 in the journal African Invertebrates.

Editor's note: This story was updated Sept. 4 to correct that scorpions are not insects.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.