Mini Human 'Brains' Grown in a Dish

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

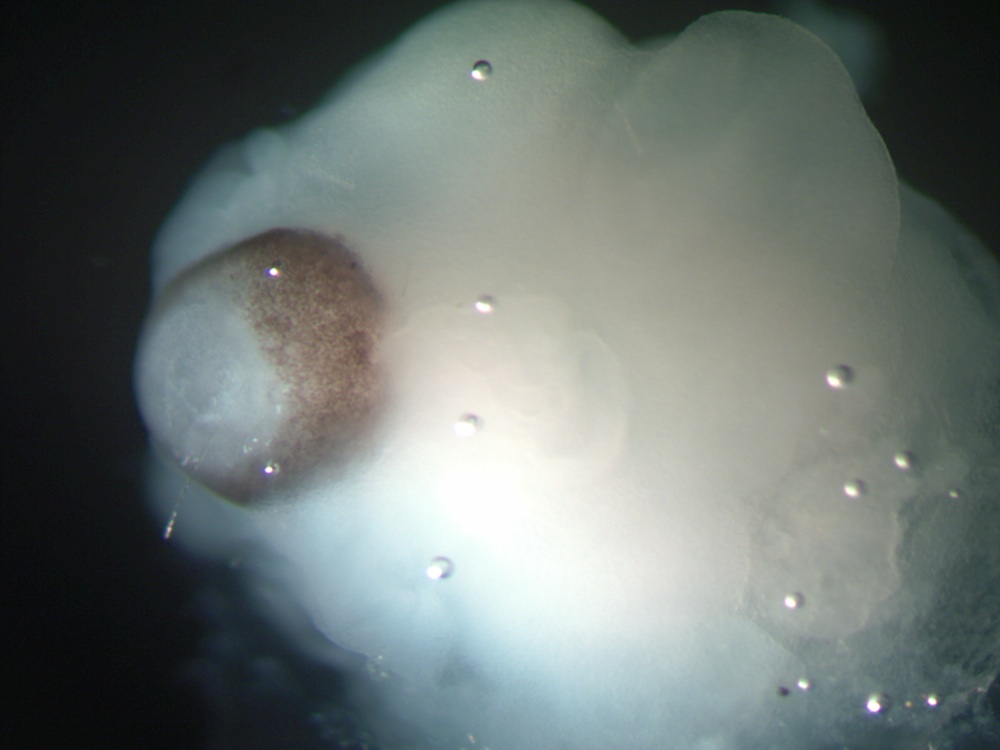

The first complete living model of the developing human brain has been created in a lab dish.

Researchers grew human stem cells in an environment that encouraged them to form pea-size gobs of brain tissue, which developed into distinct brain tissues, including a cerebral cortex and retina.

The minibrains were used to model microcephaly, a human genetic disorder in which brain size is dramatically reduced. Though not capable of consciousness or other higher cognitive functions, the minibrains allow scientists to study aspects of the developing human brain that are difficult to model in animals. [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

"The mouse brain is not always a good model system for the human brain," study researcher Jüergen Knoblich, of the Austrian Academy of Science's (IMBA) Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna, said at a news conference. "Our system allows us to study human-specific features of brain development."

Other groups have grown small pieces of neural tissue in the lab before, but none has been able to successfully grow tissue that contained both a cortex — the specialized outer layer of the brain — and other brain regions, Knoblich said.

To create the minibrains, Knoblich and his team took human embryonic stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells — both types of cells with a capacity to develop into any kind of tissue — and grew the cells in conditions that allowed them to form a tissue called neuroectoderm, which develops into the nervous system. The researchers embedded fragments of the tissue in droplets of gel to create a scaffold to guide further growth. They then transferred the droplets to a spinning bioreactor that increased nutrient absorption.

After 15 to 20 days, the tissue formed minibrains called cerebral organoids, each enclosing a fluid-filled region, much like the cerebral ventricles that contain cerebrospinal fluid in the human brain. After 20 to 30 days, some of the organoids formed defined brain areas, including a cerebral cortex (the brain's complex outer layer); retinal tissue, the light-sensitive part of the eye; meninges, the membranes that envelope the brain; and choroid plexus, which produces the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain. [Infographic: See How the Mini Brain Grew in Lab]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The minibrains grew 2-3 millimeters (0.08-0.1 in) in diameter, and have survived in lab dishes for 10 months so far. Their size is limited, because they lack a circulatory system to provide nutrients and oxygen to their core regions. As a result, the brains could not develop the many layers seen in a real human brain, the researchers said.

In addition to modeling how a healthy human brain develops, the organoids can be used to model brain disorders. Knoblich and his colleagues used their minibrains to study microcephaly, a disorder not easily studied in mice because their brains are already smaller than human ones. They took skin cells from a microcephaly patient and reprogrammed them into stem cells, which they then grew into brain organoids.

The mini microcephaly brains grown from the patient's cells were smaller than ones grown from normal tissue, but had more neuron growth. The results suggest the brains of microcephaly patients develop neurons too early, before their brains have grown large enough. Other experiments showed the orientation in which the stem cells divide could also play a role in the disorder.

Biologist Gong Chen of Pennsylvania State University, who was not involved with the research, called it "a remarkable achievement," adding, "it opens the door for many studies on the human brain using human neurons."

This method of growing minibrains in a lab could be used to or test medications, or to study other brain disorders. "Ultimately, we would like to move to more common disorders, like schizophrenia and autism," Knoblich said, though he added that it's premature to speculate when scientists will develop minibrains complex enough to do so.

The research was detailed online today (Aug. 28) in the journal Nature.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 5:15 p.m. ET August 28 to cite where the study was published. It was updated at 5:58 p.m. ET to correct Gong Chen's affiliation.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus

![Scientists can now grow functional mini brains for study. [See full infographic]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/wXpZg9325wAYmpTNRtnExU.jpg)