Lions, Camels and Elephants, Oh My! Wild Kingdom Proposed for U.S.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

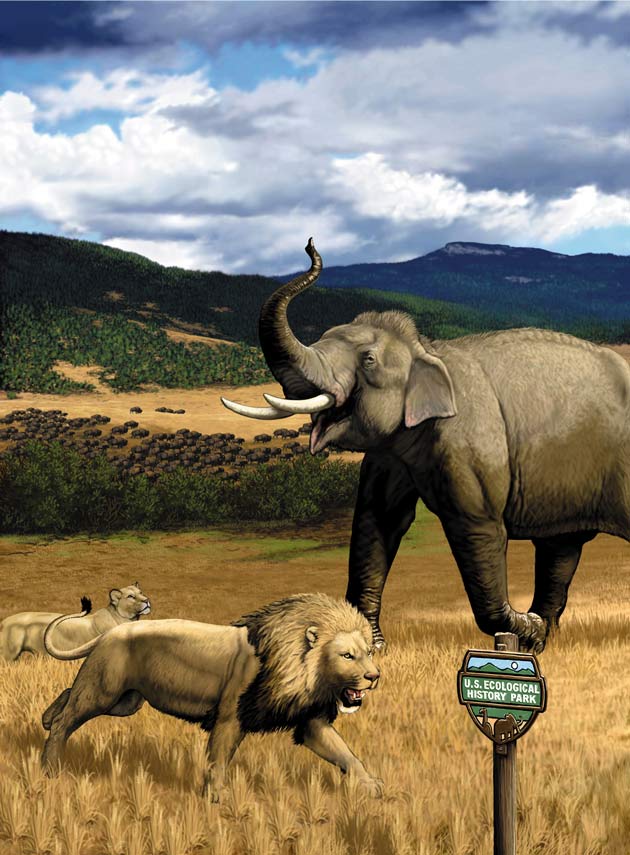

Cheetahs, lions, camels and elephants would roam wild in the United States under a new proposal to re-introduce large animals similar to those that humans hunted to extinction long ago.

The U.S. Ecological History Park, as it is billed by scientists, would help preserve species that are under increasing pressure for survival in Africa. It would also recreate a more balanced predator-prey relationship in the Great Plains and Southwest, an ecological diversity that has been absent for more than 10,000 years thanks at least in part to hunting pressure.

The idea, similar to one already underway in Siberia, is laid out in the Aug. 18 issue of the journal Nature by a dozen ecologists and conservationists at 10 universities and institutions.

The park, where large and sometimes dangerous predators would roam free, could be an economic boon to depressed farming regions that humans are fleeing from anyway.

The scientists would like to start now, using large tracts of private land, and expand the effort through the century.

"If we only have 10 minutes to present this idea, people think we're nuts," admits Harry Greene, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Cornell University. "But if people hear the one-hour version, they realize they haven't thought about this as much as we have. Right now, we are investing all of our megafauna hopes on one continent -- Africa."

Better than rats

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One justification for "rewilding," as the scientists call it, is that one way or another, we humans have a dramatic effect on the animal kingdom and ecology in general, so a proactive approach is better than letting the world go to the dogs. Or, in this case, to the rats.

In the absence of elephants and large predators, which together stomp the ground and keep other animals on the run, landscapes will come to be dominated by dandelions, rats and other undesirables, the scientists write.

Large predators can be "keystone species" that are crucial to shaping the flora and fauna of an entire range.

A modern example is the widespread disappearance of wolves and grizzly bears in parts of the West, again at the hands of humans. Elk populations soared. Elk eat willows, which beavers rely on, and so beaver populations in Colorado declined by up to 90 percent, the authors state. Fewer beavers meant fewer dams, and the reduced wetlands caused willow populations to decline 60 percent in some areas.

The paper’s lead author is Cornell graduate student Josh Donlan.

"Humans will continue to change ecosystems, cause extinctions, and affect the very future of evolution -- either by default or design," Donlan told LiveScience. "The default scenario will surely include ever more pests and weed-dominated landscapes and the extinction of most large vertebrates."

Cheetahs, woolly mammoths and relatives of the camel were just a few of the large mammals that roamed America during the Pleistocene era, which ended 10,000 years ago as the last Ice Age retreated. Studies have shown that their demise was due largely to hunting by humans, not from climate change as one theory held.

Their absence has altered the biodiversity of the continent and potentially the evolution of other animals. Large prey such the antelope-like pronghorn of the Southwest evolved lightning speed over millions of years to escape cheetahs, for example.

Start now

The park would actually involve multiple locations and phases of introduction, beginning immediately.

One first step would be to import endangered camels from the Gobi desert to the American Southwest, where they might gobble woody plants that now rule some landscapes.

Small numbers of African cheetahs and elephants from Asia and Africa could immediately be introduced on private property in the United States. The endangered cheetahs are close relatives to cats that roamed prehistoric America. Elephants are related to mammoths.

The elephants could bring economic benefit by their natural ability to manage grasslands and the potential for ecotourism, the scientists say.

Financial benefit is a key to the whole plan, in fact. The researchers cite the more than 1.5 million annual visitors to the semi-wild San Diego Zoo as an example of the draw that might be expected in a Pleistocene Park.

The scientists realize they have an uphill battle to gain public support. The controversy surrounding the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park shows the "clear obstacles" faced by any rewilding effort, Donlan said.

"Obviously, gaining public acceptance is going to be a huge issue, especially when you talk about reintroducing predators," Donlan said. "There are going to have to be some major attitude shifts. That includes realizing predation is a natural role, and that people are going to have to take precautions."

- A Pleistocene Park in Siberia

- How Humans Alter Ecosystems Today

- Prehistoric Humans Wiped Out Elephants

- Scientists Aim to Revive the Woolly Mammoth

- Top 10 Beasts and Dragons

Lions and People Killing Each Other in Tanzania

Image Gallery

Invasive Species

Which Animal

is the Ugliest?

You Decide >>>

The Study's Authors

Josh Donlan and Harry W. Greene, Cornell University

Joel Berger, Wildlife Conservation Society

Carl E.Bock and Jane H. Bock, University of Colorado, Boulder

David A. Burney, Fordham University

James A. Estes, U.S. Geological Survey

Dave Foreman, Re-wilding Institute

Paul S. Martin, University of Arizona

Gary W. Roemer, New Mexico State University

Felisa A. Smith, University of New Mexico

Michael E. Soule of Hotchkiss, Colorado

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus