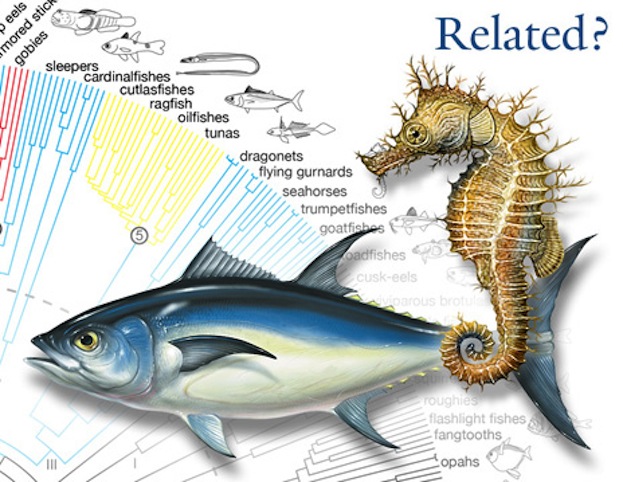

Surprising Fish Cousins: Tuna & Seahorses

Spiny-rayed fish rule the underwater world.

In the past 100 million years, fish with spiky dorsal and anal fins — an effective anti-predator device — have occupied every nook and cranny of the planet, said Peter Wainwright, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Davis. The group includes more than 90 percent of coral reef fish species and almost everything humans commercially fish, including bass, pollock and tilapia.

Now, Wainwright and a team of researchers have pieced together a new family tree for this gigantic brood, with more than 18,000 species living today. Using both genetic tools and fossils, the "phylogeny" reveals unexpected links between some spiny-rayed fish, such as tuna and seahorses. The findings were published July 15 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"There are all these sorts of relationships no one had any inkling of," Wainwright told LiveScience. "For a fish fanatic like me, these results are sort of life-changing. Until now, we really had no idea how these huge groups of fish were related."

For example, scientists used to put tuna and swordfish in the same taxonomic group, said Thomas Near, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University and lead study author. The revised family tree shows that tuna and seahorses are more closely related than tuna and other fast fish like swordfish and barracuda. The big, warm-blooded tuna and the tiny seahorse are from sister groups that diverged about 100 million years ago, while flounders and other flatfish are the nearest kin to swordfish, the study found. [Image Gallery: Freaky Fish]

Another remarkable result of the analysis is the absence of any sign of a fish extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period 66 million years ago, when a mass extinction wiped out the dinosaurs. "When you look at diversification rates, there's no hiccup. There's no hint of a mass extinction event," Wainwright said.

Instead, the spiny-rayed fish were in the midst of a massive takeover, as they occupied every watery niche on the planet between about 150 million to 50 million years ago. Those fin spines became everything from the lure on an anglerfish to a remora's sucker disc to a sailfish's eye-catching sail.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With the new family tree, Wainwright said he has found that coral reefswere invaded by different fish species about 50 times, instead of having a single common fish ancestor that evolved into a variety of forms.

For unknown reasons, the entire fish family downshifted their diversification (the rate at which new species are created) about 40 million years ago, the study found. Wainwright said there's no mass extinction event proposed at that time, and the study authors speculate that the fish may have simply filled all their available habitats on Earth. "The pattern continues to the present, as far as we can tell," Wainwright said. "We cannot say why."

The spiny-rayed fish separated from lampreys, sharks and sturgeon and from the ancestors of salmon and trout about 150 million years ago. Along with their distinctive fin spines, they can also protrude their upper jaw, creating suction that draws in prey.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.