Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists can use daredevil comets to probe regions of the sun's complex, hellishly hot atmosphere that are off-limits to spacecraft, a new study reports.

The sun's magnetic field caused the tail of Comet Lovejoy to wiggle in strange ways during the icy wanderer's suicidal plunge through the solar atmosphere in December 2011, researchers have found, suggesting that the close approaches of such "sungrazer comets" can help astronomers better understand Earth's star.

"I liken Lovejoy and these other comets to sort of naturally occurring celestial explorers, in that they're going there for us and, in a way, returning data that we can use in a complementary way," said study lead author Cooper Downs of Predictive Science Inc. in San Diego. [Photos of Comet Lovejoy's Dive Through Sun]

A death dive

Comet Lovejoy dove through the sun's corona, or outer atmosphere, in mid-December 2011, passing just 87,000 miles (140,000 kilometers) above the solar surface.

Temperatures in the corona can exceed 2 million degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 million degrees Celsius), so most scientists expected the 660-foot-wide (200 meters) Lovejoy to be destroyed during the close pass.

The hardy comet emerged on the other side of the sun, however, stripped of its tail but still in one piece. (For a little while, at least — it broke up a few days later, Downs said.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A number of instruments on the ground and in space watched Comet Lovejoy's fiery plunge, including NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and twin STEREO (Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory) spacecraft.

Downs and his team studied observations made by SDO and STEREO in extreme ultraviolet wavelengths. They discovered that charged particles in Lovejoy's tail undulated while passing through the corona, clearly affected by the region's magnetic field.

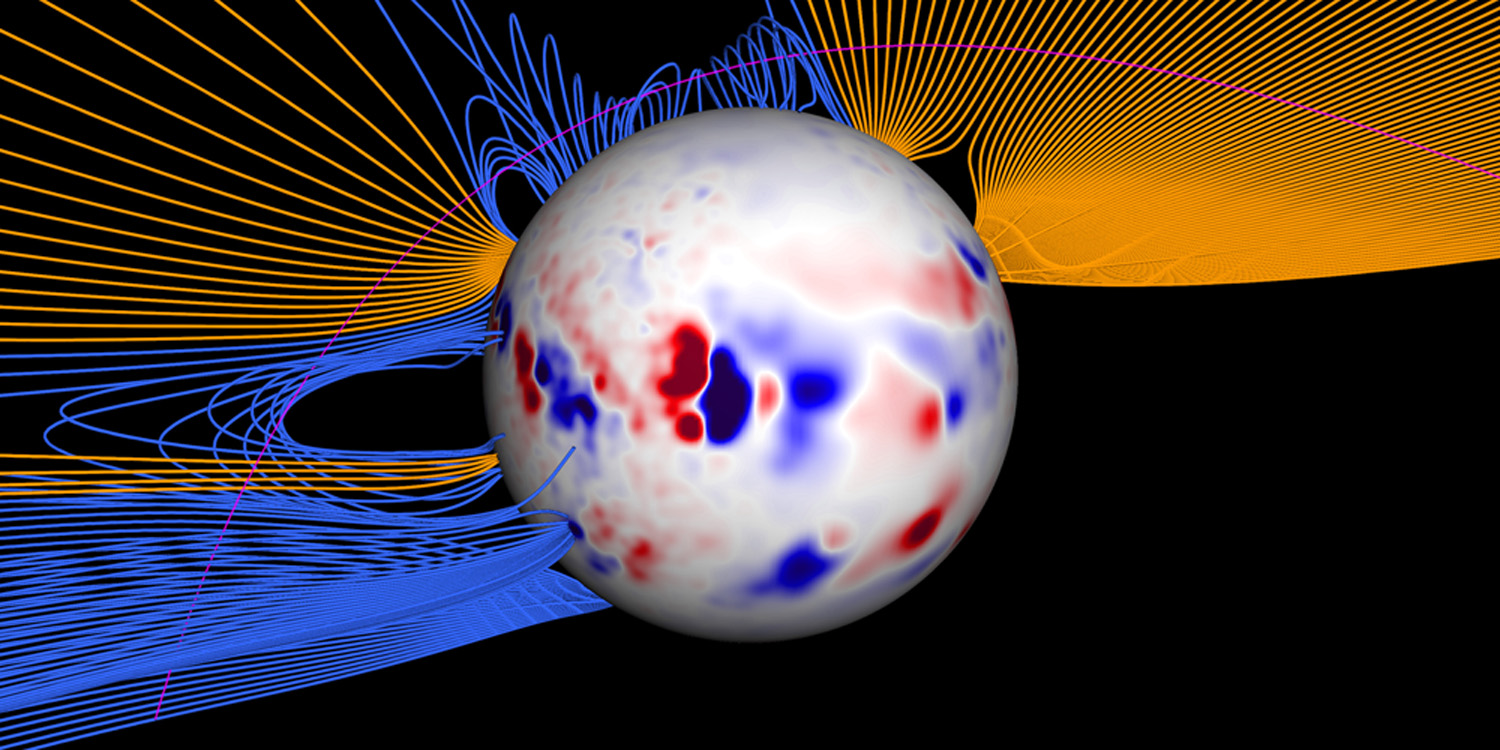

The scientists then used these observations to test out two different models of the corona's magnetic field, one relatively simple and the other much more complex. The complex one won out, better explaining the tail particles' movement.

The corona shapes most of the solar storms that affect Earth, so such findings could have practical applications down the road, researchers said.

"If we want to be able to predict space weather consequences, we really need to develop good and accurate models," Downs told SPACE.com. "Of course, a critical component of that is testing these models, and in new ways."

The study was published online today (June 6) in the journal Science.

More sungrazers coming

Solar physicists will have other chances to probe the corona, for Lovejoy isn't the only comet with suicidal tendencies.

Lovejoy belongs to a family of dirty snowballs known as Kreutz sungrazers, which apparently are the remains of a giant comet that broke apart centuries ago. Astronomers have spotted about 1,600 Kreutz comets to date, with more doubtless awaiting discovery.

Some non-Kreutz comets graze the sun as well. One such daredevil is Comet ISON, which will come within 800,000 miles (1.3 million km) of the solar surface this November. If it doesn't break up before this close pass, ISON could become one of the brightest comets ever seen, scientists say, perhaps blazing as brightly as the full moon.

"If [ISON is] really visible this low in the corona, this close to the sun, we're hoping it can tell us something about the acceleration of the solar wind, and also the magnetic field in this region," Downs said. "We'll definitely be trying to model that field and get something out of it, but we'll see what happens."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus