Common Cold DNA Deciphered, Congestion Continues

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

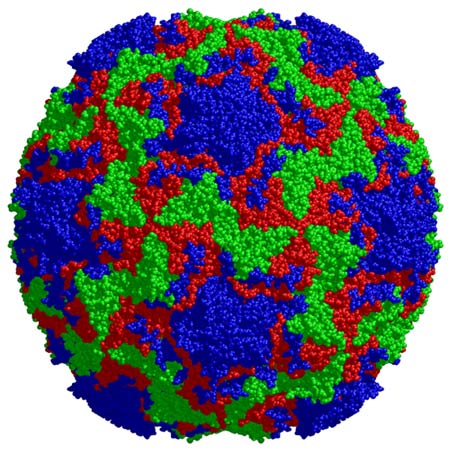

Snifflers of the world rejoice: Scientists are one step closer to finding effective treatments for the common cold now that researchers have deciphered the genetic code of the ubiquitous virus.

While a full-blown cure for the common cold is not expected anytime soon, the mapping of the human rhinovirus's genetic blueprint will help scientists better understand and combat this highly contagious pathogen. In the meantime, there are always ways to help keep yourself from succumbing to the coughs and congestion.

Researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and the University of Wisconsin-Madison cracked the cold's code by sequencing the genomes of all 99 known strains of rhinovirus. This allowed the team to determine how all the strains were related to one another, creating a viral family tree of sorts.

The work, detailed in the Feb. 13 issue of the journal Science, confirmed some ideas about the nature of the human rhinovirus while providing a few surprises.

"We know a lot about the common cold virus," said study co-author Ann Palmenberg of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, "but we didn't know how their genomes encoded all that information. Now we do, and all kinds of new things are falling out."

What's known

There isn't just one type of cold virus; there are potentially hundreds of strains of human rhinovirus (HRV) that are grouped into at least two species: HRV-A and HRV-B. The new research hints at two more possible species, HRV-C and HRV-D.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All these species and strains account for why we go through so many tissues and cough drops: Immunity to one strain doesn't protect you against other strains.

And we're constantly exposed to cold viruses. Adults can come down with a cold two to four times a year, while schoolchildren can catch as many as 10 colds annually. Colds can also trigger asthma attacks, and there is suspicion that colds in early childhood could program the immune system to develop asthma, the researchers noted.

Previous research suggests that the direct and indirect costs from the common cold run the United States about $60 billion a year, including medical care, wrongly-prescribed antibiotics and missed work days.

Though some classification of the virus could be made before, having the complete genome at hand will help researchers better understand how the cold virus invades our bodies and how it mutates or changes with time.

Remaining mysteries

Right now, cold remedies are still the standard tissues, decongestants, cough medicines and Mom's chicken soup (really — it helps loosen the mucus that's clogging up your nose). But these only treat the symptoms, not the disease itself, which has proven more difficult.

Finding any anti-viral drugs that could combat the virus — or better still, a vaccine that would prevent infection in the first place — has been virtually impossible because there are so many strains, those strains could mutate, and scientists didn't know exactly how the viruses invaded the body's cells.

"There has been no success in developing effective drugs to cure the common cold, which we believe is due to incomplete information about the genetic composition of all these strains," said study co-author Stephen Ligget of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

The completed genome has let scientists see what parts of virus strains might be similar, and where they might be most vulnerable to drugs.

If two or more strains bind to the same places on cells to enter them, for example, the same drug could potentially be used for all of those strains. With similar information, "we can predict which drugs can take them out," Palmenberg said.

Such drugs are likely years away from being developed though, and many strains will likely be too different for an all-purpose vaccine.

The new study, funded by the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health, also showed that a person can be infected with more than one strain at a time, and those strains can swap genes to make an entirely new strain while they're in there together. The researchers hope that their study will shed light on which parts of the genome are most likely to switch partners in a genetic do-si-do.

What you can do

The only way to fully insulate yourself from catching a cold — becoming a hermit in some remote part of the world — isn't very practical, but there are things you can do to reduce the chance you'll get sick when those around you are sneezing up a storm:

- Wash your hands — Simple, but effective. Use soap, it's more effective than alcohol-based sanitizers. And anti-bacterial soaps won't help because the cold comes from a virus.

- No Eskimo kisses — Cold viruses love the mucus membranes in noses and eyes, so steer clear when a loved one is sick. A peck on the cheek won't hurt you though.

- Don't worry, be happy — One study has shown that people who exhibit more positive emotions get sick less often.

- Cover up — if you really want to be germ free, you can wear a surgical mask, which can help keep your from breathing in those nasty viruses.

- The Common Cold: Myths and Facts

- Common Cold News and Information

- How Should I Treat a Cold?

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus