Tree Stranglers: Vines Overtaking Tropical Forests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A creeping menace is taking over the planet's tropical forests, a brand of tree-hugging vine whose embrace if you're a tree is of the sinister kind.

Lianas, a type of woody vine, are increasingly abundant across forests in Central and South America , according to new research on the plants.

"They seem to be increasing while trees are not," said Stefan Schnitzer, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and co-author on a recent study, the first of its kind, which combined data from eight previous investigations of lianas across Central and South America.

In fact, some parts of the Amazon are now called liana forests, Schnitzer said, because the climbing vines have taken over. "And they're not particularly pretty forests, I may add," Schnitzer said.

Schnitzer said it's a scene that would be familiar to anyone who has spent time in the southeastern United States, where another type of prolific liana kudzu is taking over the trees.

However, the creeping abundance of lianas has implications beyond mere aesthetics.

"Lianas prevent trees from growing," Schintzer told OurAmazingPlanet. "They're really good competitors."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tree backstabbers

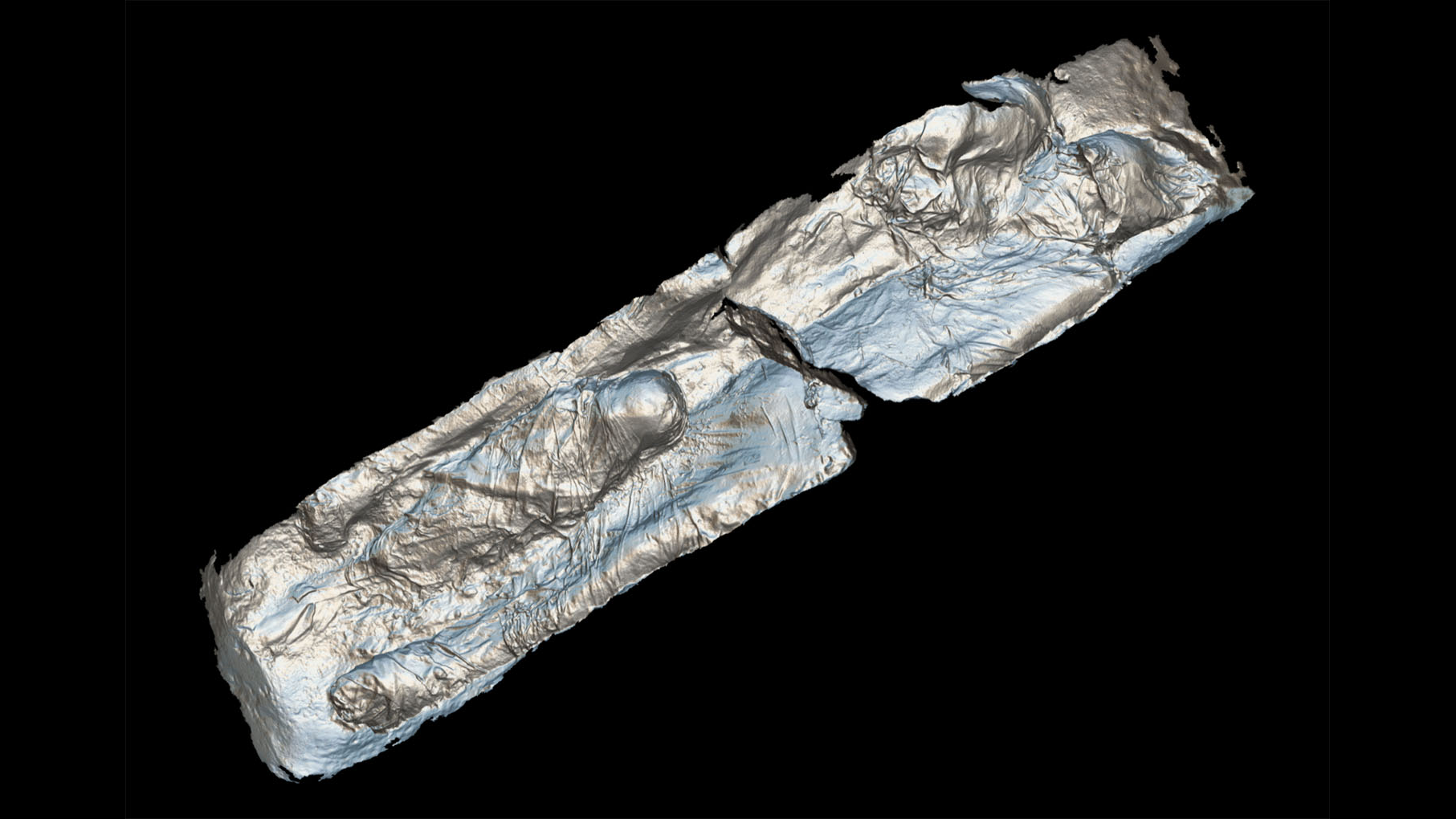

Lianas use the sturdy trunks of trees as a kind of living trellis, allowing the vines to slither up the length of a tree and reach the canopy, beating out the trees for resources such as water and sunlight.

And a shift in the makeup of forests a higher percentage of lianas, a lower percentage of trees can have big ramifications for everyone on the planet, because trees are an excellent carbon sink (meaning they suck up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it for many years), whereas lianas are not.

Trees put a lot of their energy into growing sturdy trunks. "That's where all the carbon is stored, and it can be stored for hundreds and hundreds of years," Schnitzer said.

Lianas don't have to bother because they hitch a ride on tree trunks. "They have a lot less wood volume, so they don't store nearly as much carbon," Schnitzer said.

What's to blame

Schnitzer said the study data suggest there are several main culprits behind the increase in lianas.

First, if trees are removed from forests, whether by natural or human means, more sunlight penetrates the darkness of the forest floor, which allows lianas to flourish. In addition, it appears that lianas can thrive in drier conditions, and when greater amounts of carbon dioxide are found in the atmosphere, two conditions now seen in some places in the Amazon.

Schnitzer said more study is required to see how big a part all these factors play, and how they may be intertwined.

However, the invading vines aren't bad news for all the residents of the tropics.

Sloth highway

"Lianas are important for animals in tropical forests, because they connect from one tree to the next tree, and provide a lot of resources," Schnitzer said.

Because the hardy vines can thrive in the dry season, they can flower and produce fruit when other plants don't, providing a source of food.

In addition, lianas' vast network of entangled tendrils provide an inter-tree expressway, allowing creatures to climb from tree to tree with relative ease, and providing more real estate for nesting, sleeping and eating.

"These things are really important structural components of the forest for animals," Schnitzer said. "Monkeys, sloths, they're always climbing on lianas. So you can't go in and say, 'Let's just cut down all the lianas, and the forest will be OK.''

Schnitzer said the increase of the vines is a more nuanced issue. "We're hoping that this study will get people to realize this is an important phenomenon," Schnitzer said, "and in another five or 10 years, we'll have more data."

Schnitzer spoke with OurAmazingPlanet from Panama, where he works with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. The study he co-authored is published in the journal Ecology Letters.

- Image Gallery: Plants in Danger

- Image Gallery - Hold Your Nose: 7 Foul Flowers

- In Images â?? Trekking Through the Amazon

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus