Bus-Sized Dinosaur Breathed Like Birds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

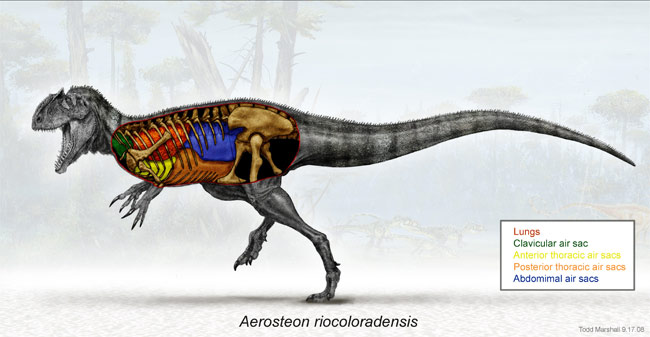

A huge carnivorous dinosaur that lived about 85 million years ago had a breathing system much like that of today's birds, a new analysis of fossils reveals, reinforcing the evolutionary link between dinos and modern birds.

The finding sheds light on the transition between theropods (a group of two-legged carnivorous dinosaurs) and the emergence of birds. Scientists think birds evolved from a group of theropods called maniraptors, some 150 million years ago during the Jurassic period, which lasted from about 206 million to 144 million years ago.

"It's another piece of evidence that's piling onto the list of things that link birds with dinosaurs," said researcher Jeffrey Wilson, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan.

Flighty dinosaur

Called Aerosteon riocoloradensis, the bipedal dinosaur would have stood at about 8 feet (2.5 meters) at its hips with a body length of 30 feet (9 meters), about the length of a school bus.

Wilson along with University of Chicago paleontologist Paul Sereno and others discovered the skeletal remains of A. riocoloradensis during a 1996 expedition to Argentina. In years following the discovery, the scientists cleaned up the bones and scanned them with computed tomography.

The scans showed small openings in the vertebrae, clavicles (chest bone that forms the wishbone) and hip bones that led into large, hollow spaces. When the dinosaur lived, the hollow spaces would have been lined with soft tissue and filled with air. These chambers resembled such features found in the same bones of modern birds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While there's no evidence to suggest the dinosaur wore a coat of feathers or flew like a bird when alive, the new findings suggest it breathed like one.

Modern birds have rigid lungs that don't expand and contract like ours. Instead, a system of air sacs pumps air through the lungs. This novel feature is the reason birds can fly higher and faster than bats, which, like all mammals, expand their lungs in a less efficient breathing process.

Other avian air sacs line the spinal column and are thought to lighten birds' skeletal bones, also making flight easier.

"We're beginning to learn more about how the specialized respiratory system of the birds evolved by tracing some of the steps in their ancient relatives," Wilson told LiveScience. "And the cool thing is these animals look nothing like birds."

Lighten the load

Wilson and his colleagues suggest the hollow bones and possible air sacs could have served various purposes, such as making the dinosaurs efficient breathers.

Weighing as much as an elephant, Aerosteon also may have used the openings to shuttle away unwanted heat from its body core, Wilson said.

Another advantage of airy bones would be to shed some pounds from the leviathon. "It may have an important functional role in making the backbone light but also strong," Wilson said of the air-sac system. "When you get big, weight is important."

Several dinosaur fossils have shown suites of bird-like features, though no carnivorous dino has been found with such evidence of air sacs in its clavicle. For instance, past research has shown maniraptoran dinosaurs, such as velicoraptors and tyrannosaurs, were equipped with structures that move the ribs and sternum during breathing in modern birds.

Scientists also have found air sacs in the vertebrae of sauropods, a group of long-necked, long-tailed, plant-eating dinosaurs that lived in the Late Triassic and Middle Jurassic periods, about 180 million years ago.

The clavicle discovery is detailed today in the online journal PLoS ONE.

- Dino Quiz: Test Your Smarts

- Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus