Neanderthal Brains Grew Like Ours

Score one more for Neanderthals.

A new study has found that Neanderthal brains grew at much the same rate as modern human brains do, knocking down the idea that they grew faster in a style considered more primitive.

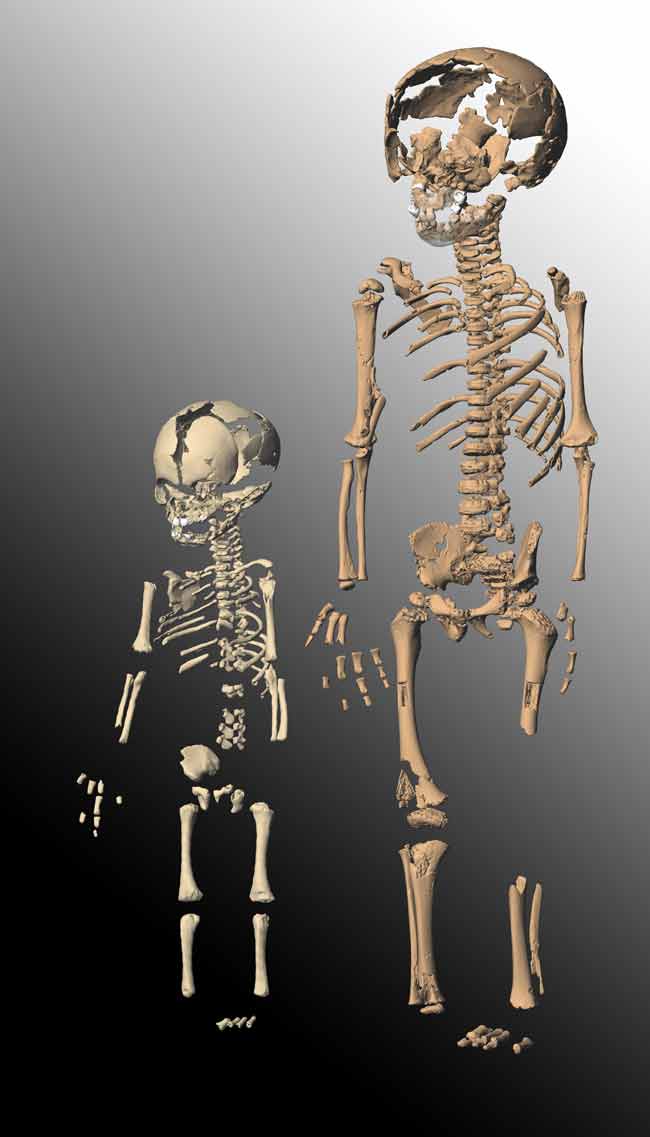

The recent discoveries of two very young Neanderthal skeletons, as well analysis of a little-studied infant Neanderthal skeleton, allowed the researchers to trace how quickly the species' skulls grew.

The results showed a greater similarity than expected between modern humans and Neanderthals, a hominid species that lived in Europe and Asia between 130,000 and 30,000 years ago.

Live fast, die young

Studies of brain growth rates tell anthropologists a lot about the lifetime development of a species.

Originally some scientists thought Neanderthals grew up faster than modern humans, reaching their adult size sooner, as, for example, chimpanzees do. Chimps, our closest living relatives, mature much faster than we do, but also die younger.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's the old saying, 'live fast, die young,'" said researcher Christoph Zollikofer of the University of Zurich in Switzerland. "It was thought that this was the primitive way, and that modern humans were further evolved into a slow life history, living a longer lifespan. Our major conclusion is there was no real difference between Neanderthal and modern human life history — they were equally slow."

The discovery that modern humans and Neanderthals share this trait means that we probably both got it from our last common ancestor, he said.

"Now we can say these so-called modern features of slow growth and development are actually old," Zollikofer told LiveScience.

Lucky finds

The research was made possible by some lucky archaeological discoveries. A team of Japanese scientists uncovered skeletons of two Neanderthal children — a 2-year-old and another about 18 months old — in a cave in Syria. Another fossil of an infant Neanderthal had previously been found in Russia, but not studied in detail or described in an anthropological journal. The skeletons all date from between 45,000 to 50,000 years ago.

Zollikofer and a team of researchers led by Marcia Ponce de León analyzed all three specimens and made 3-D computer reconstructions of the whole skeletons based on the available fragments — about 70 to 80 percent of the complete skeletons. They also studied the skeletons' teeth to estimate their ages by their dental development.

The team found that baby Neanderthal heads were slightly larger than today's baby human heads, just as adult Neanderthal skulls typically are slightly larger than today's adult humans'. Paleontologists have yet to unearth any baby skeletons of our direct Homo sapiens ancestors from the corresponding point in geologic time, but adult Homo sapiens skulls were about the same size as adult Neanderthals', so the researchers think the Homo sapiens infants then might have also had similar-sized skulls.

The discovery adds to the growing evidence that Neanderthals and the Homo sapiens ancestors of today's humans had a lot more in common than previously believed. The fossil record has increasingly turned up evidence of Neanderthals possessing cultural skills, such as tool-use and some form of language. These behaviors were once thought to be solely held by modern humans.

"In many respects they are much more similar to modern humans than we thought," Zollikofer said. "First it was tools, then eating meat, altruism, all kinds of features that seem to be deeply rooted to evolution. And if you look at the most recent genetic studies, they also show deep similarities. The picture gets much more detailed, and we have more and more knowledge about possible differences and possible commonalities."

The researchers detail their findings in the Sept. 8 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and A. H. Schultz Foundation.