College Kids Get T. Rex Anatomy All Wrong

Even though Tyrannosaurus rex is arguably the most recognizable dinosaur, college students asked to draw the prehistoric beast tend to get it all wrong, researchers say.

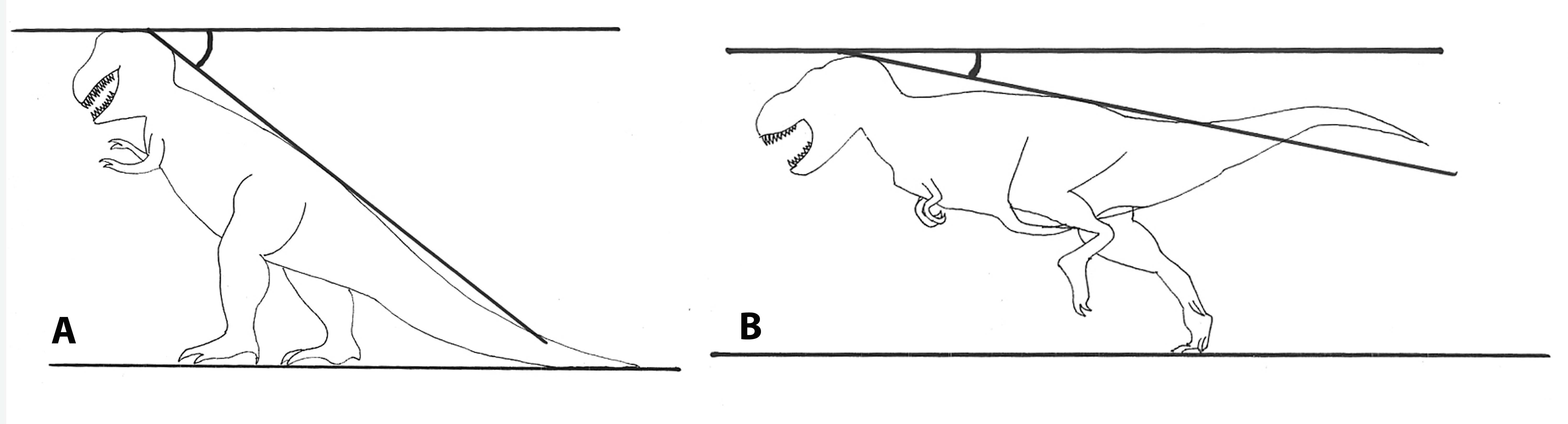

The average student's idea of T. rex more closely matches Barney the purple dinosaur, standing upright instead of pitched all the way forward like the real thing, a new survey showed.

"Our conclusion was that maybe students are imprinted with this image from their very earliest years," Cornell paleontologist Robert Ross said in a statement. "Even after they've seen 'Jurassic Park,' it doesn't change."

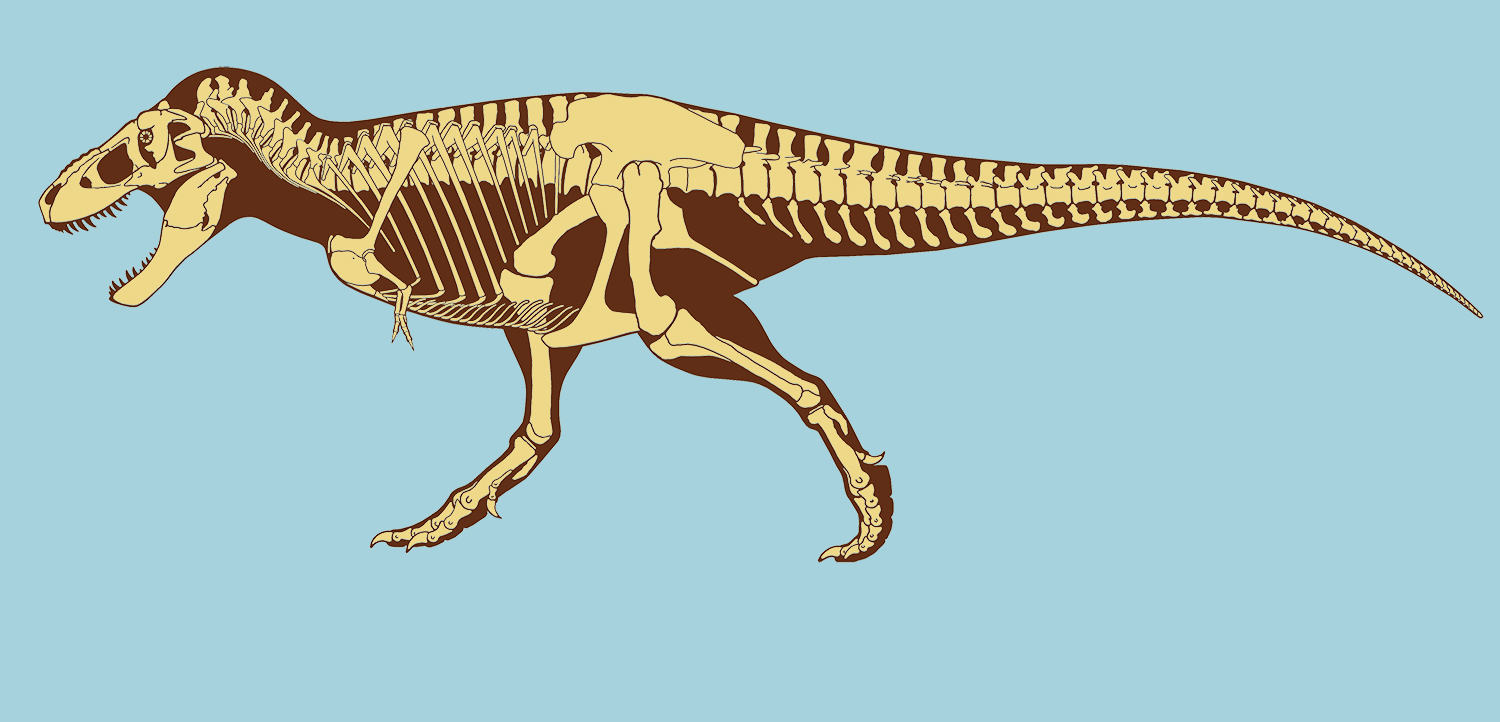

Paleontologists estimate that T. rex, which lived 67 million to 65 million years ago during the late Cretaceous Period, was about 40 feet (12 meters) from head to tail and weighed as much as 9 tons (about 8,164 kilograms). Since the 1970s, scientists have known that this huge body hovered horizontally over the dinosaur's strong legs, not upright as initially believed, and that the dinosaur likely stood 15 feet to 20 feet tall (4.6 m to 6 m).

But students' perceptions of the dinosaur's posture are stuck in the early 1900s, Ross and his colleagues at Cornell found. In their survey, 63 percent of pre-college and 72 percent of college-age students drew the T. rex standing upright with a dragging tail. The average spinal angle of the students' dinosaurs (as measured from a horizontal line) was 50 to 60 degrees, the researchers found, but the correct angle should be much smaller.

The Cornell team said bad dinosaur anatomy in pop culture, in forms ranging from chicken nuggets to cartoon characters, contributes to a "cultural inertia" that allows the public consciousness to cling to outdated science. Warren Allmon, director of the Cornell-affiliated Paleontological Research Institution, said educators must consider these preconceptions that students bring to the classroom.

"You have to meet students where they are, and start where they are," Allmon said in a statement. "This is just another example of that. It's one that still boggles my mind."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study will be detailed in a forthcoming issue of Journal of Geoscience Education.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus