How Rock Pigeons Got Their Mullets

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

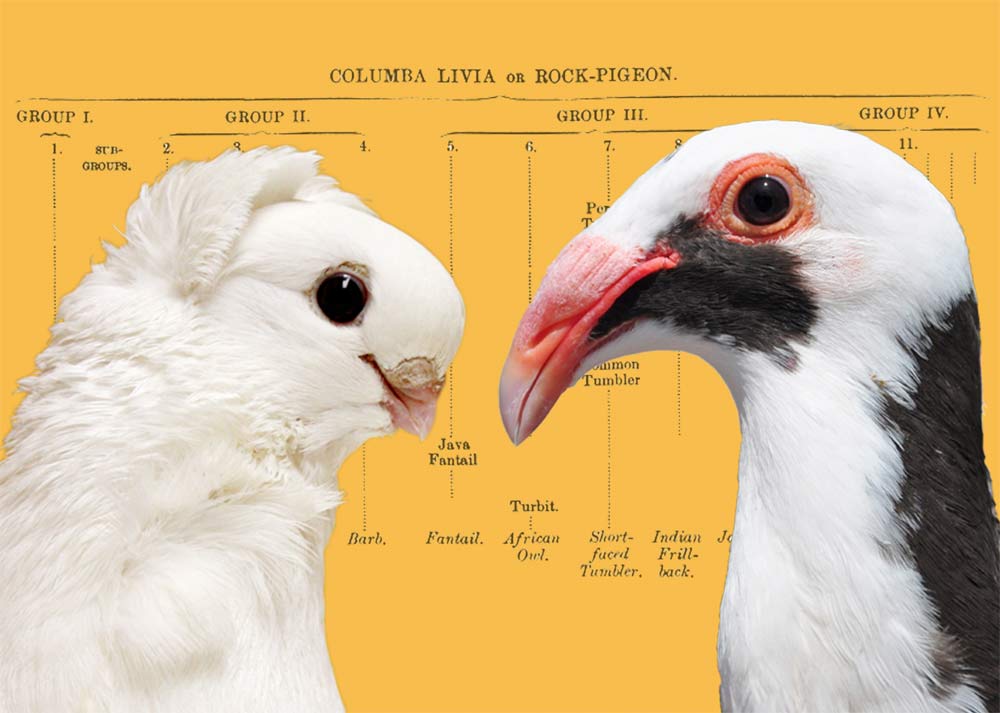

The rock pigeon's funky hairdos have been pinned to a single gene mutation that signals head and neck feathers to grow up rather than down in a tamer fashion, report researchers who have just decoded the bird's genome.

"A head crest is a series of feathers on the back of the head and neck that point up instead of down," study researcher Michael Shapiro said in a statement. "Some are small and pointed. Others look like a shell behind the head; some people think they look like mullets. They can be as extreme as an Elizabethan collar."

In addition to diverse "updos," the rock pigeon — a single species (Columba livia) — shows incredible variety in several other traits, including beak size, vocalizations, color patterns and bone structure, among its 350 different breeds.

"We're interested in pigeons, because they're this beautiful example of amazing diversity within a single species," Shapiro, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Utah, told LiveScience. [Crazy Crests: Photos of Stunning Pigeon Hairdos]

Pigeon genes

To look at the genetics behind the diversity, Shapiro and his colleagues focused on a male rock pigeon from the Danish tumbler breed, assembling more than a billion chemical bases that pair up to form "rungs" on the "DNA ladder." Discrete units of DNA make up an organism's genes.

They also sequenced the partial genomes of two feral pigeons (one from a U.S. Interstate 15 overpass in the Salt Lake Valley, and the other from Lake Anna in Virginia) and 38 other rock pigeons from 36 breeds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers lined up the genomes of birds with and without crests, finding a particular region in the genome that was highly differentiated between the two groups. Using a software tool the researchers found the so-called EphB2 gene could explain the difference; Shapiro and his colleagues say the gene acts like a switch for head crests, keeping feathers growing downward in its normal form and upward when mutated.

"We know this group of genes plays an important role in feather development," Shapiro told LiveScience, "though the role of this gene isn't completely understood yet."

He added that other genes likely control the variation in these head crests.

And while the fancy hairdos don't show themselves until pigeons are juveniles, the mutant gene is at work much earlier, reversing the direction of feather buds at the molecular level when the birds are just embryos.

Pigeon roots

The genetic results also revealed some of the pigeons' roots, showing the owl breeds (a group with short beaks) likely came from the Middle East, as they showed close ties with breeds known to have originated in Syria, Lebanon and Egypt, Shapiro said.

The findings also match historical accounts of trade routes: The team found a breed called fantails, which are typically associated with India, are related to breeds whose ancestors are known to have come from Iran.

"There are accounts from a time of Emperor Akbar in India that verify there were pigeons being exchanged between those two regions — India and Iran — or at least the Middle East," Shapiro said during a phone interview. "Akbar was apparently getting gifts of pigeons."

The study, which is detailed today (Jan. 31) in the Science journal's website Science Express, involved collaboration between China's BGI-Shenzhen, the University of Utah, the University of Copenhagen and the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Shapiro also noted the study would not have been possible without various pigeon breeders. "The pigeon breeders have been absolutely essential in this research, in material and expertise. And we could not have done it without them."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus