Scary Mollusk Mouths Had Humble Beginnings

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

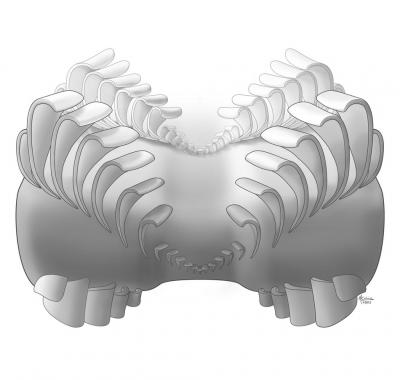

The inside of a mollusk's mouth is a fearsome sight to behold. Most mollusks, from giant squids to predatory slugs, have radulas, or tonguelike structures covered with interlocking teeth that move like a conveyor belt to slice and steer prey down the throat. But a new analysis of 500-million-year-old fossils suggests that the earliest radulas were used merely to slurp up mud-covered food from the seafloor.

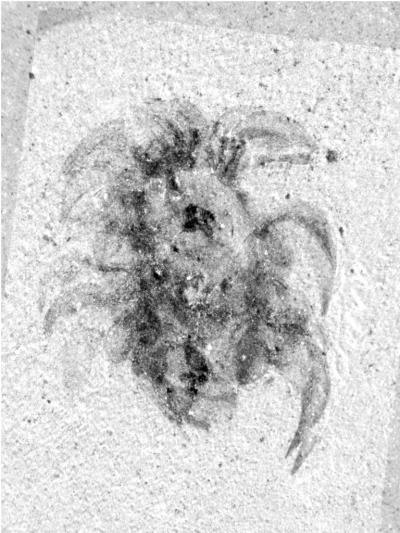

University of Toronto graduate student Martin Smith had been examining hundreds of fossil specimens of the Cambrian animals Odontogriphus omalus, a naked slug, and Wiwaxia corrugata, a soft-bodied bottom-dweller covered with spines and scales. (The creatures would have lived at about the same time as an odd shrimplike creature that could grow up to 6 feet (1.8) in length and was equipped with spiny limbs on its mouth for snagging prey.)

Scientists had been unsure about where these animals fit in the evolutionary tree, whether they were members of the groups Mollusca, Annelida, or a group containing molluks and annelids. The basis for the confusion had to do with the organisms' bizzare mouthparts, which resembled both the radula of mollusks and the jaws of some annelid worms.

Now Smith, using a special electron microscope, was able to see details of the mouths of these fossils that suggest they represent early mollusks.

"I put the fossils in the microscope, and the mouthparts just leaped out," Smith said in a statement from the University of Toronto. "You could see details you'd never guess were there if you just had a normal microscope."

The mouthparts of the animals look like shorter and squatter precursors to modern radulas, Smith said. He determined that these animals likely had two to three rows of about 17 teeth that would have moved around the end of a tongue in the conveyor-belt fashion seen in mollusks today, scooping food, like algae, from the seafloor.

"When I set out, I just hoped to be a bit closer to knowing what these mysterious fossils were," Smith said in the statement. "Now, with this picture of the earliest radula, we are one step closer to understanding where the [mollusks] came from and how they became so successful today."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study was published this week in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus