Green Thumbs Caught Red-Handed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

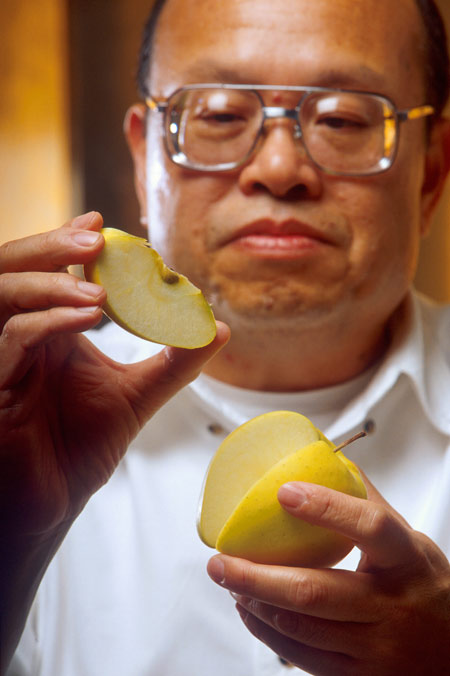

How can you tell if food labeled as organic truly is organic, that is, grown without synthetic fertilizers and pesticides? You could just trust the farmer. OK, that idea is admittedly laughable, especially now that organic is big business and major food conglomerates are capturing an ever greater share of the organic food market with the goal of reducing costs by whatever means necessary. Scientists in Spain, trusting chemistry more than corporations, are developing a method to sniff out food grown with synthetic fertilizers. Their technique, published in the January-February issue of the Journal of Environmental Quality, relies on the detection of an isotope of nitrogen found in organic food but not in non-organic food. This doesn't identify other high crimes of the organic food industry — such as organic Twinkies, organic milk from permanently penned cows, or organic fruits flown in from around the world, oil dependency be damned — but it's a start. After all, next to farming, cheating is humankind's second oldest profession. You are what you eat Synthetic fertilizers contain nitrogen derived from the atmosphere. This is rather cheap, considering that air is nearly 80 percent nitrogen gas (N2) and no one owns the atmosphere, although pilots do pay a fine for flying over Dick Cheney's air space. Atmospheric nitrogen is made mostly from the nitrogen-14 isotope, with seven protons and seven neutrons. There's virtually no isotope nitrogen-15 in the air nor, as a result, in the manufactured nitrate-based fertilizers. However, the nitrogen in manure, the primary fertilizer used in organic farming, can contain up to 20 percent nitrogen-15, according to the researchers, led by Francisco del Amor of the Instituto Murciano de Investigación y Desarrollo Agrario y Agrario y Alimentario (IMIDA) in Murcia, Spain. Plants suck up nitrogen and — with the adage true for plants as it is for people, you are what you eat — organic fruits and vegetables are loaded with nitrogen-15. Any food with no nitrogen-15 or a low N15/N14 ratio betrays the use of synthetic fertilizers. Organic, so now what The Spanish researchers said someday their method could be useful in detecting small amounts of synthetic fertilizers used by organic farmers worried about low nitrogen levels in the soil and thus the potential for a low-yield harvest. As organic farming goes global, isotope sniffers could be used by nations to monitor the integrity of imported organic food. But therein lies part of the problem: Organic methods, while good to the soil anywhere, are best applied when the food is grown and sold locally. The fuel needed to import organic fruits from Chile or Australia, for example, outweighs the environmental benefit of growing organic food. Fortunately you don't need a chemistry set to know which foods are healthy and best for the environment. Forget nitrogen isotope ratios. Just think local when possible, with no packaging. When you add miles and the necessity for boxes, that's when the trouble begins.

- Take the Nutrition Quiz

- Top 10 Bad Things That Are Good For You

- The Most Popular Myths in Science

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books “Bad Medicine” and “Food At Work.” Got a question about Bad Medicine? Email Wanjek. If it’s really bad, he just might answer it in a future column. Bad Medicine appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus