Robotics' Uncanny Valley Gets New Translation

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Today's roboticists swear by Masahiro Mori's "uncanny valley" essay about creepy human imperfections that was published in an obscure Japanese journal called Energy more than 40 years ago. But the first English translation was done between the early morning hours of 1 and 2 a.m. in a Japanese robotics lab in 2005 — a rush job that has finally received a painstaking revision in 2012.

The biggest language challenge for understanding the uncanny valley comes from the Japanese word "shinwakan" — a created concept that has been described in English as "familiarity," "likableness," "comfort level," and "affinity." Such English words fail to capture the full essence of Mori's original Japanese, said Karl MacDorman, a robotics researcher at Indiana University who served as one of the English translators for the uncanny valley essay.

"I think it is that feeling of being in the presence of another human being — the moment when you feel in synchrony with someone other than yourself and experience a 'meeting of minds,'" MacDorman said. "Negative 'shinwakan,' the uncanny, is when that sense of synchrony falls apart, the moment you discover that the one you thought was your soul mate was nothing more than smoke and mirrors."

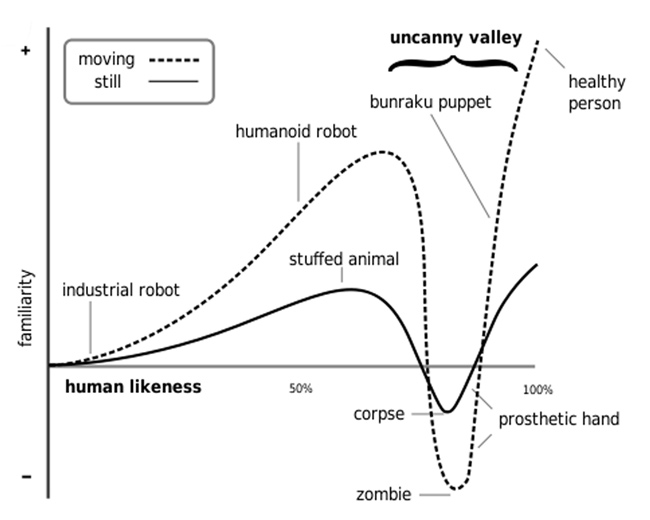

Mori's original essay included a graph that charted "shinwakan" on the "y" axis against the human likeness of a robot or other object on the "x" axis. The line of the uncanny valley climbs steadily toward a first peak as a sense of "humanness" coincides with more human-looking robots, until the line plunges abruptly into the uncanny valley right before approaching perfect human form.

The dip into the uncanny valley shows the moment when an eerie sensation is triggered in the human mind. Many researchers have pointed out that Mori's graph is not literally correct, and they still disagree about just how to define the uncanny valley. [Why Creepy Uncanny Valley Keeps Us on Edge]

But MacDorman sees the graph as a metaphor for the experience of how the uncanny feeling arises from the combination of human realism with nonhuman features. For instance, Mori gives the example of a prosthetic hand that looks human but feels stiff and cold to the touch.

Mori's 1970 essay title, "Bukimi No Tani," does not even translate directly into "The Uncanny Valley" —a more accurate translation is "Valley of Eeriness." The first English use of the "uncanny valley" phrase came from a popular robotics book by Jasia Reichardt called "Robots: Fact, Fiction, and Prediction" (Viking Press, 1978). That has led more than a few confused journalists to mistakenly date Mori's essay to 1978.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

(MacDorman and his fellow translators used the "Uncanny Valley" title for Mori's essay because the phrase had become so familiar to English speakers.)

MacDorman never meant for his 2005 translation of "Bukimi No Tani" to become the standard translation in English. He did the one-hour translation for his own personal reference with the help of a Japanese colleague, Takashi Minato, at Hiroshi Ishiguro's Android Science Laboratory at Osaka University.

"Over the years, that sloppy translation became a kind of reference for those interested in the uncanny valley, so I felt obligated to fix it and have spent orders of magnitude more time doing just that," MacDorman explained.

The new translation done by MacDorman and Norri Kageki appears in IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus