Futuristic Computer Program Arrives Ahead of Computer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Quantum computers don't exist yet, but physicists already have a software program ready for them to use.

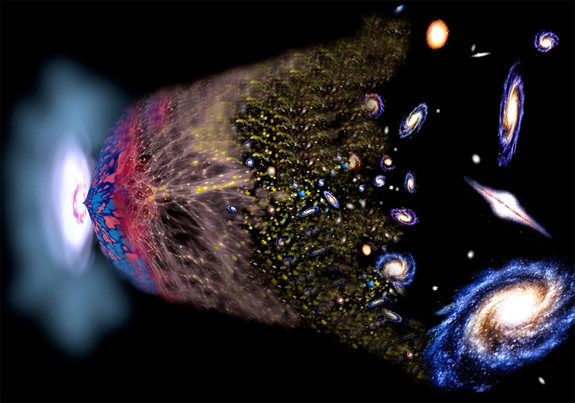

A group of scientists has designed an algorithm that they say could run on any future quantum computer to simulate all the possible interactions between two colliding particles. The program could be used to model how the universe evolved after the Big Bang, when conditions cooled enough for the formation of subatomic particles called quarks, which then collided with each other to form protons and neutrons. Eventually, the first atoms were born.

The complexity of a particle's quantum properties makes these post-Big Bang interactions far too complicated for existing computers to simulate.

Scientists are hoping for the eventual creation of computers based on the principles of quantum physics. Such computers would use quantum processor switches that could exist in both "on" and "off" states simultaneously, enabling them to consider all possible solutions to a problem at once.

Quantum computers should be able to perform incredibly complex calculations at a small fraction of the time required by current technology. [Ten Computers That Changed the World]

"We have this theoretical model of the quantum computer, and one of the big questions is: What physical processes that occur in nature can that model represent efficiently?" Stephen Jordan of the National Institute of Standards and Technology said in a statement. "Maybe particle collisions, maybe the early universe after the Big Bang? Can we use a quantum computer to simulate them and tell us what to expect?"

Jordan, a theorist in the institute's applied and computational mathematics division, and his colleagues detail their algorithm in a paper published in the June 1 issue of the journal Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Experts say quantum computers could be decades away but it's not too soon to think about what they can do.

"Universal quantum computers in the strict sense do not yet exist, but it is still of fundamental importance to know which problems they can solve more efficiently than classical computers," wrote scientists, led by Philipp Hauke of Spain's Institute of Photonic Sciences, in an accompanying essay in the same issue of Science.

The idea for quantum computers relies on the principles of quantum mechanics, the strange set of rules governing the physics of subatomic particles. In the quantum realm, particles don't firmly exist in a single place or time but hover in an uncertain cloud of possibility until forced by a measurement to take a stand. Particles also can become connected to each other through a spooky process called entanglement that allows them to share a connection even when they are separated by vast distances.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. For more science news, follow LiveScience on twitter @livescience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus