Capsizing Icebergs Pack Punch of Nuclear Bomb

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Tumbling icebergs can release energies on the level of atom bombs, scaled-down laboratory experiments with plastic bergs suggest.

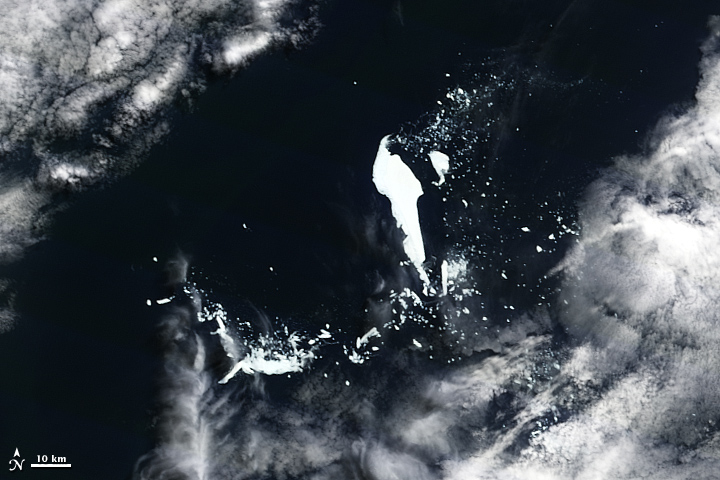

Although huge, hulking icebergs might appear relatively stable in the water, these mountains of ice can occasionally flip and roll. When large icebergs capsize, they can release a colossal amount of energy, comparable to a magnitude 5 earthquake, which can wreak havoc on their environs — a tsunami from an iceberg that calved off a glacier devastated a coastal Greenland community in 1995.

The concerns about the impacts of icebergs capsizing are heightened by global warming, which is hitting the planet's polar regions particularly hard.

"The Arctic and Antarctic regions of the Earth have 'woken up' in the last decade or so — glaciers have been retreating, and enormous ice shelves are breaking up in a matter of weeks and disintegrating into the ocean," said researcher Justin Burton, an experimental glaciologist and physicist at the University of Chicago. "This is a huge volume of ice, and much of the breakup is accompanied by capsizing icebergs."

Table-top icebergs

Investigating such tumbling icebergs could help reveal the risks they pose and determine the larger role they may play in the oceans. Lacking Superman-like muscles, scientists cannot flip giant icebergs to see how much energy capsizing them releases. Instead, Burton and his colleagues analyzed how boxy tabletop versions of icebergs behaved.

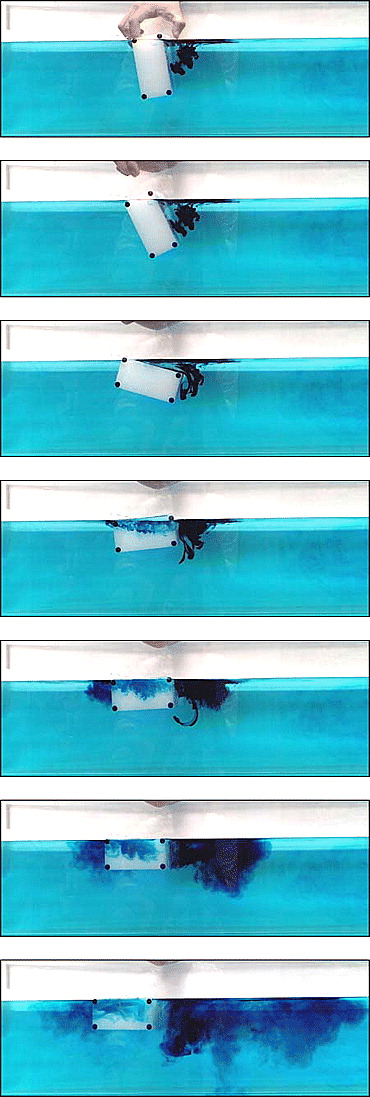

The scientists created a laboratory model of a fjord — the kind of narrow, ice-laden valley that icebergs normally calve from — as well as plastic icebergs 10.5 inches long by 4 inches high (26.7 by 10.3 centimeters), with widths varying from 1 inch to 4 inches (2.5 to 10.2 cm). The researchers held the toy icebergs by hand or by a string in an upright position in the water and then let them go to simulate their capsizing. [Video of the plastic icebergs .]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A small, round buoy in the water helped show the height of any "tsunami" waves these synthetic icebergs generated, which revealed how much energy these miniature bergs released while capsizing. Analyzing the motions of the plastic icebergs also let the investigators determine the kinetic energy they released as they rotated.

TNT equivalent

They calculated that the amount of energy released during the capsizing of a large iceberg with a thickness of about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) is enormous. "A single capsize event can release the equivalent of a Hiroshima nuclear bomb — tens of kilotons of TNT," Burton told OurAmazingPlanet. "Of course, this energy is released over a period of a few minutes, not all at once as in the case of a bomb."

Corroborating earlier research, the scientists found that the size of any tsunami waves are at most 1 percent of the iceberg's initial height. In addition, they discovered that 84 percent of the iceberg's original potential energy would end up as turbulence or heat in the surface ocean waters.

The large amount of turbulence capsizing icebergs can generate would prove especially powerful in the narrow environs of a region like a fjord. Such turbulence can severely disrupt the distinct layers of temperature and salinity (or salt content) that water normally divides into, layers that largely control the flow of heat in and out of fjords, affecting how other icebergs might calve.

"We plan to further investigate the iceberg calving process and fracture process using our laboratory setup," Burton said. "We are looking at how multiple iceberg capsize events can behave cooperatively and capsize collectively, like dominoes."

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 20 in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus