English Is an Optimistic Language, Study Suggests

When a team of scientists set out to evaluate the emotional significance of English words, they expected most would fall at the center of the scale, at neutral, while equal shares trailed out to the positive and negative ends of the spectrum.

That is not what they found, however: Instead, we appear to speak an optimistically biased language.

"I think it is a happy story," said study researcher Chris Danforth, an assistant professor of mathematics at the University of Vermont. "Fundamentally, we have this happy bias built into our language."

Overall, English words — which he described as the atoms of the language — tend to be more positive than negative, regardless of whether they are more common or more rare, they found.

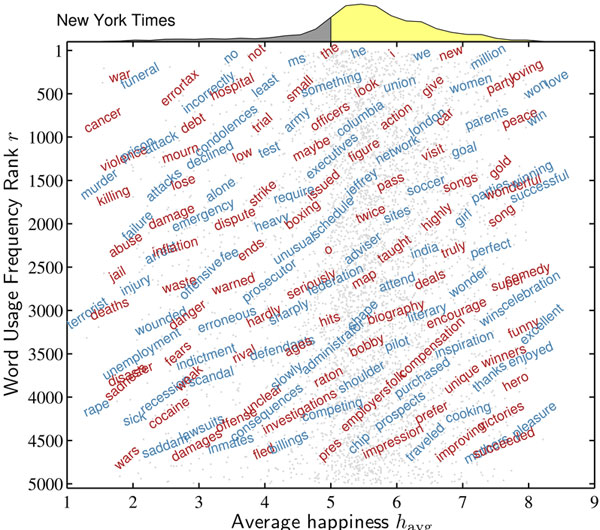

Danforth and colleagues compiled the 5,000 most frequently used words found in four sources — two decades of material from The New York Times, 18 months' worth from Twitter, manuscripts from Google Books produced between 1520 and 2008 and music lyrics from 1960 to 2007 — for a total of 10,222 words. Then, using a service called Mechanical Turk, they had 50 people evaluate each word on a scale of 1 to 9, with 1 being least happy, 5 neutral, and 9 happiest.

They found that the average score fell at 6, a full point shift toward positivity.

"That phenomenon is not dependent on which list of words you go to — it is the same shape for all of these different sources," Danforth said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Certain positively oriented words (such as"pleasure," "comedy" and "love") and other negatively oriented ones (such as "terrorist," "rape" and "cancer") naturally fall at far ends of the scale. Other words — such as "the" or "and" — are truly neutral, receiving solid 5s from evaluators. But there was also another, trickier category. [8 Meanings of the Word 'Love']

Words such as "pregnant," "beef" and "alcohol" received a wide spread of scores from their evaluators, signaling that their positivity or negativity is linkedto the context they are used in.

All were included in the analysis, published online Jan. 11 in the journal PLoS ONE. However, the researchers found that any word with an average score of between 4 and 6 could be excluded without changing the overall result.

Why the positive bent?

The reason for the positivity? The researchers think it is evidence of a pro-social nature of our language.

"[English] developed in a society that succeeded, there must be many reasons behind that, but one of them ought to be that we communicate with each other in a good way that produces good results," Danforth said.

"You need the words to be meaningful," said study researcher Peter Sheridan Dodds, an associate professor of mathematics at the University of Vermont. He pointed out negative words are less abundant but more meaningful.

"We don't run around saying them all the time — it's the boy who cried wolf sort of thing," he said. "But we are happy to say 'Have a nice day,' lots of small social things," he said.

In another analysis focused entirely on Twitter, the researchers discerned daily, weekly and annual mood cycles, as well as mood spikes associated with holidays and other events. Overall, however, they found the recent trend has been a downer, with Twitterers using less positive words over time.

Building on their work so far, Dodds and Danforth are constructing a happiness sensor they call a "hedonometer," which would draw on Twitter and other sources to provide a real-time measure of a population's mood.

"We are trying to put another dial on the dashboard of how we think about society's performance," Dodds said. The hedonometer's readings could join measures such as the gross national product or the consumer confidence index to inform policymakers and others, he said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.