'Worm-Eating' Underground Leaves Discovered in Carnivorous Plant

Sticky underground leaves help a Brazilian plant to capture and digest worms, a hitherto unknown way for carnivorous plants to catch victims, scientists find.

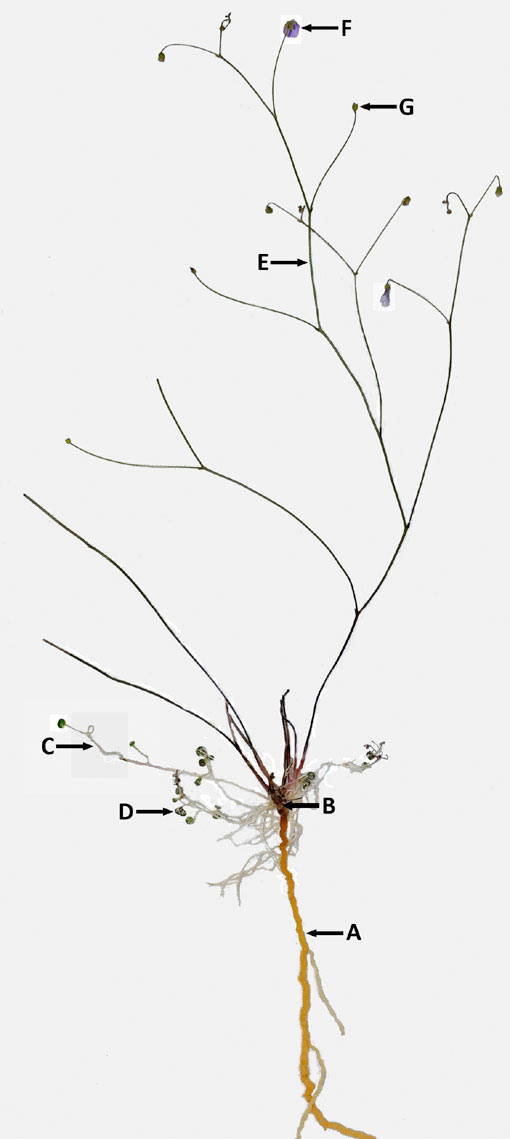

The rare plant Philcoxia minensis is found in the tropical savannahs of Brazil, areas rich in biodiversity and highly in need of conservation. Although some of the plant's millimeter-wide leaves grow above ground as expected, strangely, most of its tiny, sticky leaves lie beneath the surface of the shallow white sands on which it grows.

"We usually think about leaves only as photosynthetic organs, so at first sight, it looks awkward that a plant would place its leaves underground where there is less sunlight," said researcher Rafael Silva Oliveira, a plant ecologist at the State University of Campinas in Brazil. "Why would evolution favor the persistence of this apparently unfavorable trait?"

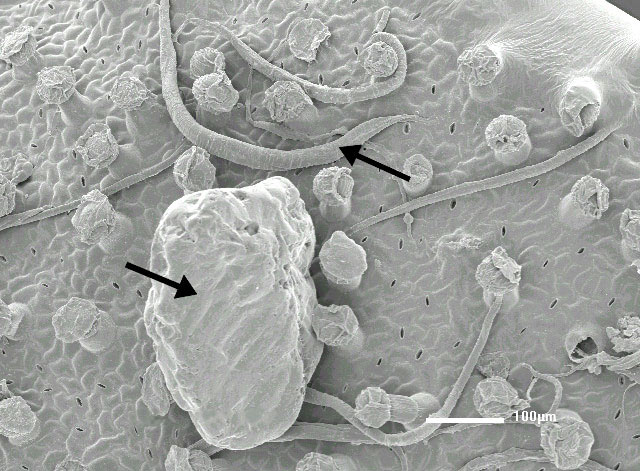

Researchers suspected the mysterious subterranean leaves of Philcoxia minensis and its relatives were used to capture animals. They share a number of traits with known carnivorous plants — for instance, Venus flytraps possess leaves covered in glands with protruding stalks that help the plant detect prey. Like P. minensis, Venus flytraps also live in nutrient-poor soils, which is apparently why they seek out prey in the first place.

To see if Philcoxia minensis is carnivorous, the scientists tested whether it could digest and absorb nutrients from the many nematodes, also called roundworms, which end up trapped on its sticky underground leaves. They fed the plant nematodes loaded with the isotope nitrogen-15, atoms of which have one more neutron than regular nitrogen-14. Essentially, the scientists placed these Caenorhabditis elegans worms on top of underground leaves of plants kept in a lab setting.

Chemical analysis of the leaves that had been covered in nematodes revealed significant amounts of nitrogen-15, suggesting the plant broke down and absorbed the worms. The leaves also possessed digestive enzyme activity similar to that seen in known carnivorous plants, suggesting that the roundworms did not decompose naturally; the researchers speculate the leaves trapped the worms and then secreted enzymes that digested the worms.

This newfound strategy suggests "carnivory may have evolved independently more times in plants than previously thought," Oliveira told LiveScience. [See Photos of Meat-Eating Plants]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I personally think these findings also broaden up our perception about plants," Oliveira added. "They might look boring for some people because they don't move or actively hunt for their food, but instead, they have evolved a number of fascinating solutions to solve common problems, such as the lack of readily available nutrients or water. Most of the time, these fascinating processes of nutrient acquisition are cryptic and operate hidden from our view."

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 9 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.