Dangling Eyes of Scary Ancient Sea Predator Discovered

The biggest, scariest predator of the ancient Cambrian oceans just got a lot more menacing: Researchers have found a pair of fossilized eyes that show the beast had excellent vision.

"The animal itself has been known for quite some time, but we've never known the detail of the eyes," study researcher John Paterson, of the University of New England in Australia, told LiveScience. "It can tell us a great deal about how it saw its world and it also supports that it's one of the key predators during the Cambrian period."

The group of predators in question, which belong to the genus Anomalocaris, could reach more than 3 feet (1 meter) long and lived in shallow oceans more than 500 million years ago. The researchers call it the "world's first apex predator," because it had highly acute vision and was much larger than other animals in the ocean at that time. It also had large claws and toothlike serrations in its mouth to tear apart trilobites.

"When you look at the animal it has these really gnarly looking grasping claws at the top of its head, for grasping onto its prey," Paterson said. "It used these grasping claws at the front to shove its prey into its circular mouth, which is also fairly fearsome looking."

Ancient predators

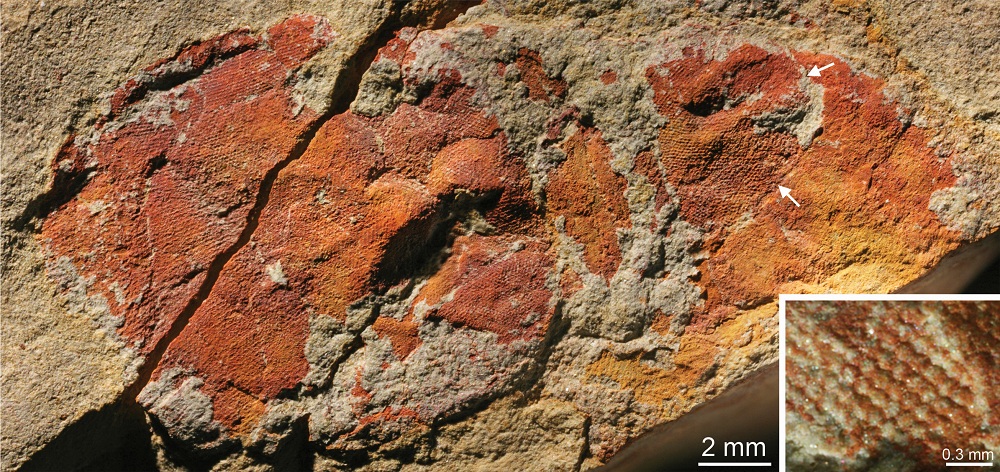

Previous fossils had preserved only the outlines of these creatures' eyes. Researchers knew the eyes were situated on stalks that protruded from its face, and they had thought the dangling eyes might be compound eyes, but weren't sure and couldn't tell how many lenses they might have had, or how sharp their vision might have been.

The eyes were discovered in a fossil from a 515-million-year-old deposit on Kangaroo Island, in South Australia. Other fossils discovered in this deposit show ancient eyes that aren't nearly as well developed, but still quite sharp compared with other animals of the day.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fossils were pried from shale rock samples: "You split them along the really fine layers in the shale with hammer and chisel, like opening the pages of the book, and hopefully something will be looking back at you for the first time in 500 million years," Paterson told LiveScience. "I was actually the one that found the pair of eyes. That was a spine-tingling moment."

Excellent eyes

Compound eyes, the type of eyes seen in dragonflies and mosquitoes, are made up of multiple individual lenses. Dragonflies, one of the few living arthropods with similarly acute eyesight, have up to 28,000 lenses per eye, while a housefly may have 3,000. These 500-million-year-old creatures had around 16,000.

Like pixels in a digital image, for compound eyes, more lenses mean a clearer picture. Based on the structure, this animal might have had an exceptionally clear, almost 360-degree view of the world around it, the researchers said. Such precise vision would have given these predators an advantage over their prey, which would need to evolve their own visual capabilities to avoid being eaten.

"It would have been very aware of its environment. It would have been a very capable predator, especially when you compare it to other animals in the same fossil sites that wouldn't have had as good of eyesight or could have even been blind," Paterson said. "Anomalocaris would have had a distinct advantage, I think."

The study will be published in tomorrow's (Dec. 8) issue of the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.