Lair of Ancient 'Kraken' Sea Monster Possibly Discovered

This article was updated on Oct. 11 at 10:42 a.m. ET

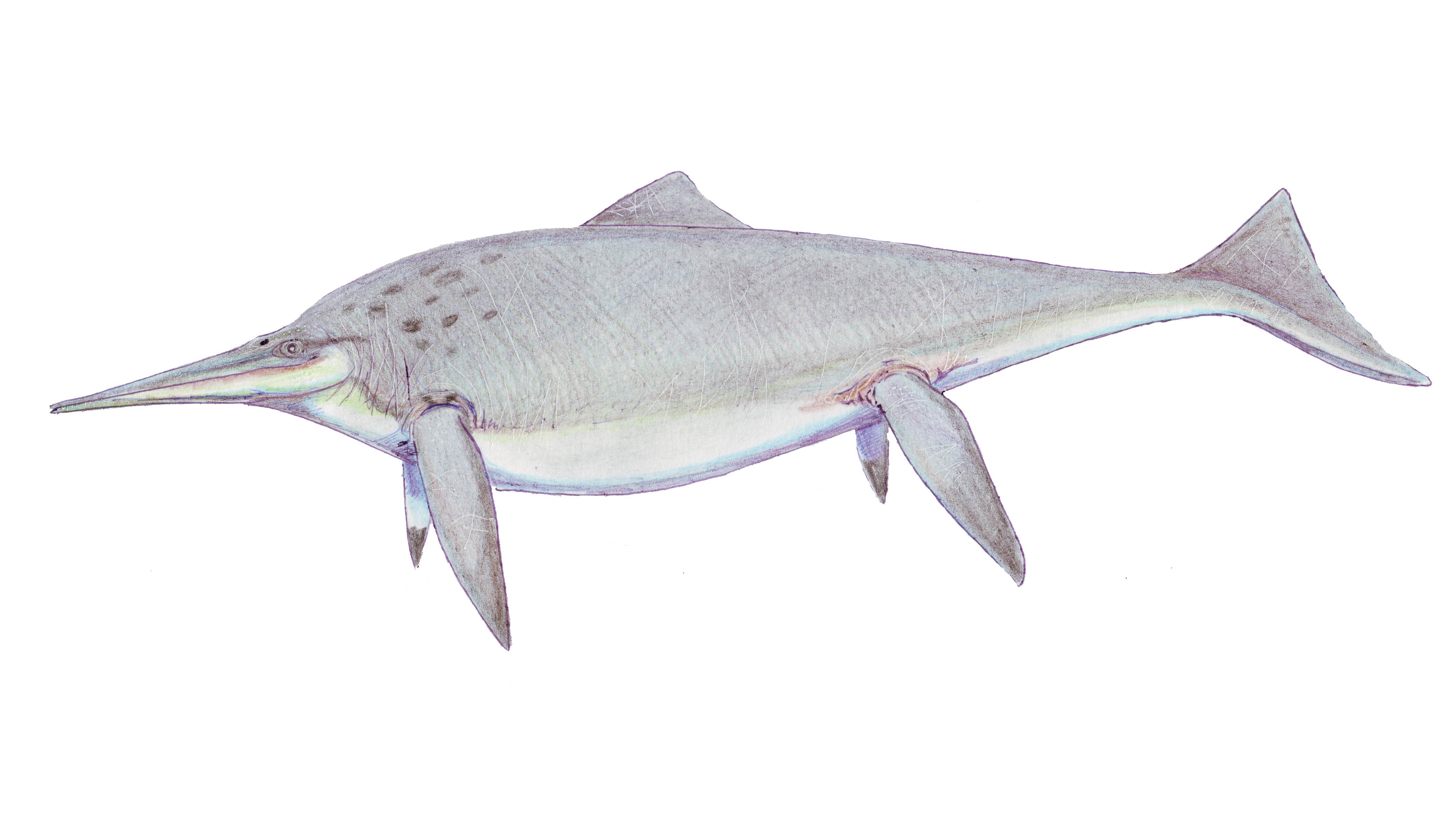

A giant sea monster, the likes of the mythological kraken, may have swum Earth's ancient oceans, snagging what was thought to be the sea's top predators — school bus-size ichthyosaurs with fearsome teeth.

The kraken, which would've been nearly 100 feet (30 meters) long, or twice the size of the colossal squid, Mesonychoteuthis, likely drowned or broke the necks of the ichthyosaurs before dragging the corpses to its lair, akin to an octopus's midden, according to study researcher Mark McMenamin, a paleontologist at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. [Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology]

"It is known that the modern octopus will pile the remains of its prey in a midden and play with and manipulate those pieces," McMenamin said during a telephone interview.

There is no direct evidence for the beast, though McMenamin suggests that's because it was soft-bodied and didn't stand the test of time; even so, to make a firm case for its existence one would want to find more direct evidence.

"No direct evidence of large cephalopods, in fact very little data at all, is problematic for proposing such a radical explanation," Glenn Storrs, curator of vertebrate paleontology at Cincinnati Museum Center, told LiveScience in an email. "Circumstantial evidence is not enough." Ichthyosaur vertebra pavements are known in shallow water settings elsewhere and the case for a deep water environment at Berlin-

Storrs added, "On top of this, the specimens are not well preserved in their current setting, thus the arrangement, 'etching' and bone breakage may have alternate explanations. To my mind, this hypothesis is like looking at clouds - being able to see what you desire."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

McMenamin presented his work Monday (Oct. 10) at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Minneapolis.

Cause of death

Evidence for the kraken and its gruesome attacks comes from markings on the bones of the remains of nine 45-foot (14 meter) ichthyosaurs of the species Shonisaurus popularis, which lived during the Triassic, a period that lasted from 248 million to 206 million years ago. The beasts were the Triassic version of today's predatory giant squid-eating sperm whales.

McMenamin was interested in solving a long-standing puzzle over the cause of death of the S. popularis individuals at the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada. An expert on the site, Charles Lewis Camp of U.C. Berkeley, suggested in the 1950s that the ichthyosaurs succumbed to an accidental stranding or a toxic plankton bloom. However, nobody has been able to prove the beasts died in shallow water, with more recent work on the rocks around the fossils by Jennifer Hogler, then at the University of California Museum of Paleontoloy, suggesting they died in a deepwater environment. [See image of kraken's lair]

"I was aware that anytime there is controversy about depth, there is probably something interesting going on," McMenamin said. And when he and his daughter arrived at the park, they were struck by the remains' strangeness, particularly "a very odd configuration of bones."

The etching on the bones suggested the shonisaurs were not all killed and buried at the same time, he said. It also looked like the bones had been purposefully rearranged, likely carried to the "kraken's lair" after they had been killed. A similar behavior has been seen in modern octopus.

The markings and rearrangement of the S. popularis bones suggests an octopus-like creature (like a kraken) either drowned the ichthyosaurs or broke their necks, according to McMenamin.

The arranged vertebrae also seemed to resemble the pattern of sucker disks on a cephalopod's tentacle, with each vertebra strongly resembling a sucker made by a member of the Coleoidea, which includes octopuses, squid, cuttlefish and their relatives. The researchers suggest this pattern reveals a self-portrait of the mysterious beast.

The perfect crime?

Next, McMenamin wondered if an octopus-like creature could realistically have taken out the huge swimming predatory reptiles. Evidence is in their favor, it seems. Video taken by staff at the Seattle Aquarium showed that a large octopus in one of their large tanks had been killing the sharks. [On the Brink: A Gallery of Wild Sharks]

"It would have been very similar to the way that the Pacific Octopus was killing sharks at the Seattle Aquarium, the main difference being that the animals were scaled up to enormous size," McMenamin told LiveScience, adding that, "ichthyosaurs are air breathers and can be drowned."

McMenamin said. More supporting evidence: There were many more broken ribs seen in the shonisaur fossils than would seem accidental, as well as evidence of twisted necks.

"It was either drowning them or breaking their necks," McMenamin said.

So where did this kraken go? Since octopuses are mostly soft-bodied they don't fossilize well and scientists wouldn't expect to find their remains from so long ago. Only their beaks, or mouthparts, are hard and the chances of those being preserved nearby are very low, according to the researchers.

With such circumstanial evidence of "the crime," McMenamin expects his interpretation will draw skeptics. And, in fact, it has. Brian Switek, a research associate at the New Jersey State Museum, writing for Wired.com, is extremely skeptical, writing, "The McMenamins' entire case is based on peculiar inferences about the site. It is a case of reading the scattered bones as if they were tea leaves able to tell someone’s fortune. Rather than being distributed through the bonebed by natural processes related to decay and preservation, the McMenamins argue that the Shonisaurus bones were intentionally arrayed in a 'midden' by a huge cephalopod nearly 100 feet long." (McMenamin worked with his wife, Dianna Schulte McMenamin on the study.)

As for how McMenamin would respond to critics: "We're ready for this. We have a very good case," he said.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.