Florida Fishing Contest Targets Spiny Alien Invaders

Beginning at sunrise one day this month, dozens of mercenaries equipped with nets, spear guns and puncture-proof gloves will slip into the warm waters off Florida's coast in search of a ruthless enemy.

Their orders? Kill for cash. And glory. And science. And a delicious meal.

Their goal? To save a suffering ecosystem from destruction.

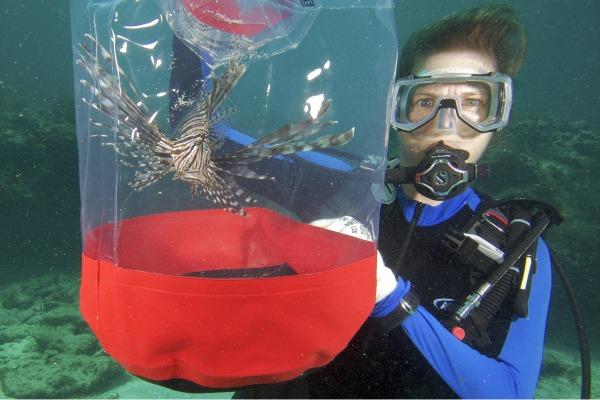

Their prey are lionfish, an invasive species equipped with venomous spines, a fearsome silhouette and a ravenous appetite that is taking over the real estate in Florida's waters.

And as part of the second annual Lionfish Derby, hosted by the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF), teams of divers can win cash prizes and help rid the environment of a menace that is gobbling up the native species with impunity.

The event kicks off on May 14 in Long Key, and is followed by two other derby days around Florida in 2011. Last year's derby brought in 664 of the offenders.

Atlantic impact

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lad Akins, REEF's director of special projects, said lionfish, a species native to tropical regions of the southwest Pacific Ocean and the Red Sea, will eat just about anything — even fish half their own size. Scientists have found as many as 60 different species of fish in lionfish stomachs. Yet in their ever-expanding empire in the Atlantic, lionfish have almost no natural enemies.

"So while they're out there consuming all of our native marine life, very, very few things are consuming them, and that's really why it’s up to us," Akins told OurAmazingPlanet. "They can have a very severe impact on our marine ecosystems."

Lionfish not only eat commercially valuable species, but also devour "cleaner species" -- fishes and crustaceans that play important roles in eating damaging algae and parasites.

Lionfish, which generally grow to between 12 and 15 inches (30 to 38 centimeters) long, have now spread to waters from North Carolina to South America, and from the eastern Caribbean, across the Gulf of Mexico and to Central America. The species is found in water as shallow as a few inches to depths of 1,000 feet (305 meters). [Related: Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Akins said the first specimen showed up in 1985, caught in a fisherman's trap. Fisheries researchers thought it was very odd. In the mid-'90s a few more showed up, and a mere decade later, the fish had spread like a spiny wildfire.

So how does a small fish take over an ocean thousands of miles from its native waters?

Through people releasing aquarium pets into the ocean — enough people have done so that there's now a breeding population and the species is exploding.

"When you swim in the Bahamas, that's all you see — they're a dime a dozen," said Carlos Estape, a dive guide and underwater photographer based in Florida. "Here, it's not like that yet, but I don’t know that we’ll be able to avoid the same situation."

Estape's team brought in 64 lionfish in last year's derby, and won a prize for netting the smallest fish — a mere 2 inches (5 cm) in length.

Lionfish feast

For next month's event, Estape said he has one goal: "Go out there and catch every one of them that we see."

Within 3 miles (5 km) of the Florida shoreline spear guns are prohibited, so Estape said he and his wife, also a dive guide, will be using nets to catch the fish, a process that takes two or three times longer than spearing.

The derby is offering up more than $10,000 dollars in cash and prizes for the biggest haul of lionfish, the largest fish and the smallest fish.

An additional perk is the massive lionfish feast that happens after the derby. "You do a cookout right on the spot," Estape said.

It turns out the invading critters are delicious.

"So far, that's about the only good thing we’ve found out about them — that they are tasty and people really enjoy consuming them," Akins said. "If they didn't taste good we'd really be in trouble."

Catching on

Cut off the venom-tipped spines with a pair of scissors (the spines deliver a neurotoxin that is quite painful, but can be neutralized by immersing the affected area in hot water), and cooking up a lionfish is easy as any other fish. Akins said the meat, which is higher in omega-3 fatty acids than tuna, is reminiscent of grouper or snapper, but tastier.

Some restaurants in Florida have begun to carry lionfish on the menu regularly, and Akins said he hopes the fish will catch on, and become a target for commercial fisheries.

In addition to providing a beach-side feast, Akins said the haul from the derby will help scientists as well, providing genetic samples for study, and aiding REEF, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Geological Survey, which are all partnered in developing technology to defend against the spiny invaders.

Estape said he and other divers don't just wait for the derby to get lionfish out of the water.

"Every time I go out I kill something," he said. "It's a beautiful fish, but we know the results if we don't control them. I can either take them out, or let them destroy our native fish population. You have to make a choice. You can't have both."

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.