Earthquake Drill This Week in Midwest: Prudent or Silly?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This week, nearly 3 million people across 11 states are gearing up for the Great Central U.S. Shakeout, a massive earthquake drill to commemorate the 200th anniversary later this year of a series of powerful earthquakes that downed trees and sent waves on the Mississippi River roaring over its banks.

At 10:15 a.m. CT on Thursday (April 28), residents will crawl under desks or sturdy tables, grab the legs of the obliging furniture, and wait for the "shaking" to stop, in adherence with the Shakeout's official slogan: Drop! Cover! Hold on!

The drill, seen by some scientists as unnecessary, is designed to include participants from school age to old age in Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Missouri.

Brian Blake, program coordinator for the Central U.S. Earthquake Consortium, said if you're indoors, taking cover beneath the dining table is the first line of defense against the unpredictable heaving of the planet.

"People here in America are injured more by things falling on them than by buildings collapsing on them," Blake told OurAmazingPlanet. "So you want to make sure a bookshelf or TV doesn't wobble off and fall on your head."

Although this is the first such drill in the middle of the country, it's modeled on similar drills in California and other known earthquake danger zones in the Pacific Northwest.

"There's a real possibility that we could have damaging earthquakes here, and people need to know what to do when the ground shakes," Blake said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

History in the quaking

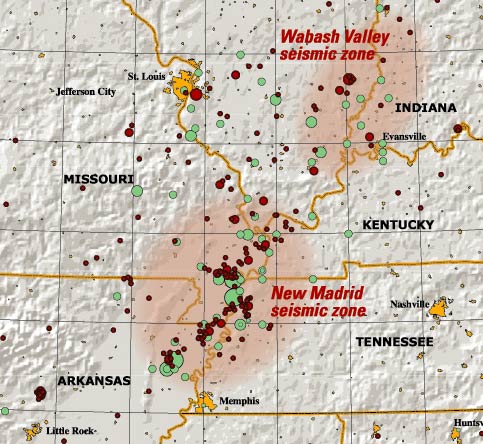

The ground has certainly shaken in the central portions of the country in the past. Between December 1811 and February 1812, three quakes occurred along the New Madrid seismic zone, a spidery network of faults stretching from around Memphis, Tenn., up through the southern edge of Illinois, and straddling the Mississippi River across Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri.

Based on the best data available, the three quakes were roughly 7.7, 7.5 and 7.7 magnitude, and caused damage over 230,000 square miles (600,000 square kilometers), according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

In Washington, President James Madison even made a note of the shaking in a letter to Thomas Jefferson dated Feb. 7, 1812: "There was one here this morning at 5 or 6 minutes after 4 o'C. It was rather stronger than any preceding one, & lasted several minutes, with sensible tho very slight repetitions throughout the succeeding hour."

Chances for disaster

Based on the region's history of seismic activity, the USGS estimates there's a 7 to 10 percent risk of an earthquake of a similar scale to the early 1800s quake — in the magnitude 7-range — within the next 50 years. That percent risk rises to 25 to 40 percent for an earthquake of magnitude 6.

Yet despite the predictions, the source of the region's subterranean jolts remains rather mysterious.

"We really don't know why New Madrid has earthquakes," said Robert A. Williams, the coordinator of the USGS's Central & Eastern U.S. Earthquake Program.

Unlike the recent devastating earthquake in Japan or the quakes that periodically shake California, which occur along boundaries between the Earth's massive continental plates, the New Madrid fault system lies within the middle of a continental plate.

Williams said it's clear the region has a long history of earthquakes stretching over thousands of years, and theories for the mechanisms responsible abound — from erosion along the Mississippi, to a remnant plate deep inside the Earth yanking down on the region, to the land slowly rebounding after the retreat of glaciers.

However, Williams said, "Despite not knowing exactly what causes the earthquakes, we do know they happen, so preparing for them is a prudent thing to do."

Will it or won't it?

But not everyone is worried about the risk of Midwestern earthquakes. Seth Stein, a professor of geology at Northwestern University in Illinois, and author of a new book about overblown estimates of quake hazard in the region, says GPS data gathered within the last 20 years indicate there's no risk of a large earthquake in the region.

"The way earthquakes work is you store up strain in the ground, and we don't see any," Stein said. "No strain, no earthquake. It's pretty simple."

Stein said GPS data show the region's faults only budge by one-fifth of a millimeter per year, in contrast to faults in California and the Pacific Northwest, which move about 250 times more — about 50 millimeters per year. "And fundamentally that motion is what produces an earthquake," Stein told OurAmazingPlanet.

However, Williams said, although the last two decades of GPS data show little to no movement along New Madrid, the USGS isn't comfortable relying on those data alone to qualify earthquake hazard in the region.

"We are funding researchers to try and come up with models to explain the low amount of motion at the surface — maybe we don't have instruments in the right places — it's an ongoing area of research," Williams said, adding that the area is an active seismic zone.

Instruments in the region record around 200 earthquakes a year, on average, which may or may not be felt at the surface, according to Sue Evers of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which is supporting participation in Thursday's earthquake drill.

Evers, based in Kansas City, Mo., said she herself will be getting under a desk on Thursday morning.

Several hundred miles to the northwest, in the Chicago's northern suburbs, Stein said he will not be climbing under any furniture.

"Of course not," Stein said. "Certainly in the last 200 years, no one has ever been killed by an earthquake in the Midwest, and there has been no serious damage from an earthquake. I think we'd be better to focus on the real problems our communities face."

New Madrid now

In the Missouri town of New Madrid, the burg that lent its name to the sometimes-contentious earthquake zone, the local schools will be taking part in the Shakeout drill.

"For our kids, it's almost like second nature," said Bridgett Masterson, the principal at New Madrid Elementary, where earthquake drills have been a part of life for at least the 17 years Masterson has worked in the school system.

In addition to tornado and fire drills, Masterson said the school conducts four earthquake drills per year, adding that there are supplies set aside in case of any kind of emergency.

"I guess because we haven't had a big one since — oh my, 1812 — it's almost like it's not scary," Masterson said. "My perception is that everybody tries to be prepared, but not scared."

- The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History

- Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes

- 7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye

Andrea Mustain is a staff writer for OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Reach her at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus