Infants Recognize Melodies Heard in the Womb

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A melody heard three weeks before babies are born can slow their hearts when they hear it again one month after birth, scientists find.

This discovery adds to the understanding of the effects of what sounds get heard in the womb, including how babies learn to perceive speech.

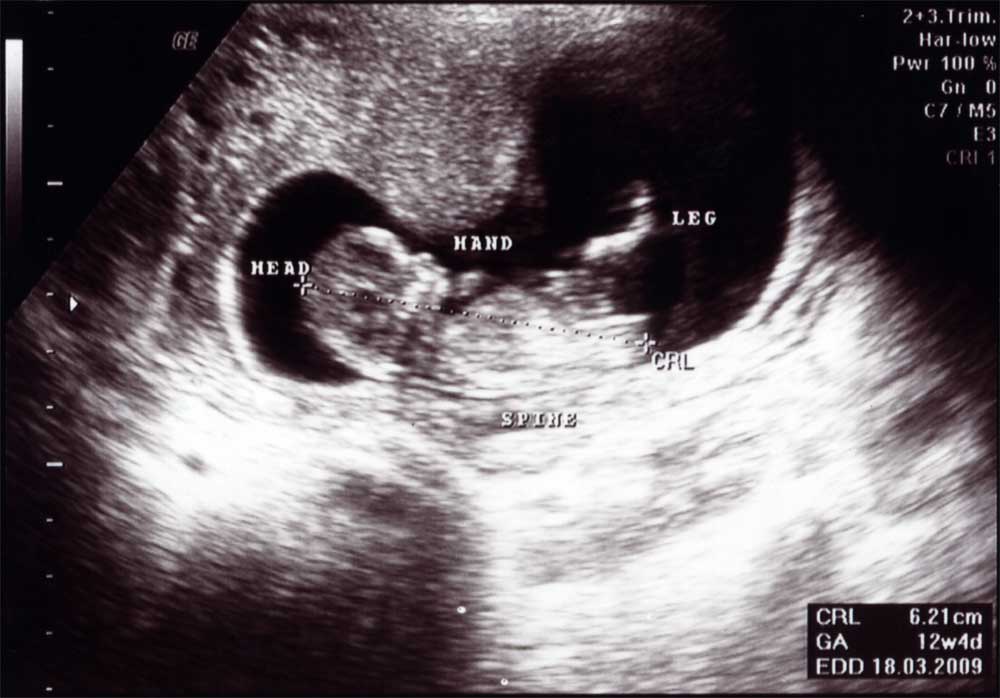

Human hearing develops during the last trimester, or three months, of pregnancy. Past research showed that infants in the womb can hear, with little or no distortion, not only the voice of theirmother but conversation near her.

By five weeks before birth, the cochlea — the spiral-shaped part of the inner ear responsible for hearing — is usually mature. To see if babies can actually remember sounds from back that far, developmental psychobiologist Carolyn Granier-Deferre at Paris Descartes University in France and her colleagues played melodies to infants inside the womb and then tested them after they were born.

"I was interested in prenatal hearing and learning since my first pregnancy almost 40 years ago," Granier-Deferre explained.

Music to the womb

Fifty women were asked to play a brief recording of a descending piano melody (one that gets lower in pitch) twice daily in the 35th, 36th and 37th weeks after their last menstrual period. (The average human pregnancy lasts 40 weeks after the last menstrual period.) The melody was nine notes long and lasted 3.6 seconds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the women's 50 infants were 1 month old, both the descending melody and an ascending nine-note piano melody were played to the babies while they slept in the researchers' dimly lighted laboratory.

The scientists found that on average, the heart rates of the sleeping babies briefly slowed by about 12 beats a minute with the familiar descending melody, and by only five or six beats with the unfamiliar ascending melody.

"Our data shows that a melodic sound, which is an important characteristic of a voice and was frequently heard during prenatal development, produces a much stronger cardiac response than occurs without that experience," Granier-Deferre told LiveScience. "The large heart rate deceleration means the 1-month-old infants paid more attention to that melody than they did to other melodies, even though they had not heard it for six weeks."

Mama's voice

These results suggest newborns will orient toward and pay more attention to what may be "their mother's melodic sounds than they will to those of other women, and will pay more attention to other similar sounds, like female voices in general, than they will to even less similar sounds, like male voices," Granier-Deferre said.

Moreover, these findings add to evidence suggesting that prenatal hearing can help infants perceive the sounds of speech.

"It was long known that newborns could discriminate or perceive most of the acoustic properties of speech. The prevailing theoretical view is that these capacities are mostly independent of previous auditory experience and that newborns have an innate bias or skill for perceiving speech," Granier-Deferre said. "Our results show that merely exposing a human fetus' developing auditory system to complex stimuli can affect how it functions — I think the newborn's capacities to perceive speech get physiologically 'built in' during development of the auditory system."

So should pregnant women play music to their developing offspring? "When fetuses are old enough to hear fairly well, about four to five weeks before birth, they will be exposed to all the sounds of the maternal environment, so there is simply no biological need for more auditory stimulation — more is not always better, especially during development," Granier-Deferre said.

"If mothers want to encourage music appreciation in their children, they can begin after the baby is born, when they can see and know what pleases or annoys, which she will never know from the behavior of her fetus."

Furthermore, when it comes to devices that mothers put directly on their skin to play music, "this kind of stimulation can be harmful to the fetal ear if it is too loud or left on too long or applied too early during the inner ear development," she added. "Now, if the mother wants to sing to her baby, why not? A mother's singing is a wonderful part of the natural sound environment."

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 23 in the journal PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus