Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

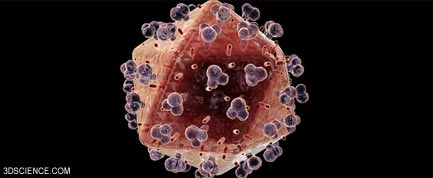

A new study slamming the link between male circumcision and reduced HIV transmission is itself being slammed by HIV scientists who say the author is not qualified to make such claims and worry his findings will be accepted as scientific consensus by the public.

Numerous studies by biologists and medical researchers have indicated circumcision can significantly reduce a male’s risk of contracting HIV during heterosexual sex.

However, in a study released on June 20 in the online journal PLoS One, John Talbott says such claims are based on faulty statistical analyses. Talbott re-analyzed the data used in a widely cited study published in a 2004 issue of the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (JAIDS) and found that male circumcision (or lack thereof) is not a good predictor of a country’s HIV infection rate. Rather, he proposed, the number of infected prostitutes in a country should be used to estimate that area’s HIV infection rate.

Talbott is a former vice president of the investment banking division of Goldman Sachs in New York City and has no formal training in biology or epidemiology.

Lack of skepticism

Since its publication, Talbott’s study has garnered increasing coverage from news outlets and bloggers, some of whom have treated the findings as undisputed fact. This concerns HIV researchers who say Talbott’s own analysis is misleading and that it suggests, falsely, that African women are more likely to be prostitutes than women in other parts of the world.

“Not only is this epidemiologically questionable … but it seems like a misleading and potentially harmful assertion to be making, which could even be perceived by some as playing on racial stereotypes,” said Daniel Halperin, an HIV specialist at Harvard University and a co-author on the earlier study that Talbott disputes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other researchers worry Talbott’s claims could leave the public with a false impression that the link between HIV and circumcision is still a hotly debated issue. “There’s no doubt about it. John Talbott’s really out on a limb here,” said Helen Weiss, an HIV researcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “It’s just not a question anymore. And it’s quite frustrating that he’s getting all this publicity, because we’ve moved beyond.”

In his study, Talbott refers to other research that found that up to 4.3 percent of the women in African capital cities are prostitutes. These sex workers, many of whom are infected with HIV, are the primary vectors for transmission of the disease among the population, Talbott contends.

Talbott’s critics say his study does not explain why countries such as Angola, Madagascar and the Philippines have relatively low rates of HIV infection (about 4 percent, 2 percent and less than 0.1 percent, respectively) despite their having very active sex-worker communities.

Talbott contends that these outliers do not discredit the trend his analysis shows. “Whenever you do a regression analysis for 77 countries, it’s very easy to go in and find the three data points that don’t support the theory perfectly,” Talbott said in a telephone interview. “Just because there’s a correlation across 77 countries, it doesn’t mean it applies to every country.”

Other explanations for the disconnect between prostitute numbers and HIV infections, Talbott said, might be that many countries are underreporting their HIV infection rate, or that countries with high prostitution rates but low rates of infection do a better job of keeping track of and testing resident prostitutes.

“For example, in Argentina…they keep them in the bars and restaurants,” Talbott said. “[The prostitutes] don’t cruise the street, and [the governments] monitor and test them regularly.”

A proven method

Ultimately, Halperin said, results from ecological studies—which rely on the statistical analysis of data from populations or groups of people rather than individuals—such as the one Talbott is refuting are not solid enough to base health policy decisions on.

Ecological studies “are in many ways the lowest rung of the food chain in epidemiology. Randomized trials are the strongest level of evidence," Halperin said.

Halperin said the findings of the 2004 JAIDS paper have been validated by results from other studies, including randomized trials that involved following the infection rates of circumcised and uncircumcised African men. Those trials found that circumcision was up to 60 percent effective in preventing male HIV infection during heterosexual sex.

"It is the higher-level data, like randomized trials, which have convinced many international organizations including WHO and UNAIDS regarding the protective effect of male circumcision for heterosexual HIV transmission," Halperin said. "They have concluded, after much internal and external debate, that an intervention which is at least 60 percent effective should be made available to those men who seek out the service."

“They were very skeptical at first…but once people actually sat down to look at the data, you’re not left with a choice really if you want to do something about HIV prevention,” Weiss said.

Weiss stresses that scientists are not saying circumcision is the only way to curb HIV infection. Rather, they are recommending that it be integrated into other intervention strategies, such as regular condom use and behavioral changes.

“Everybody wishes there was a vaccine or there was some easy way of reducing HIV risk,” Weiss said. “Nobody wants a surgical intervention which has got some risk associated with it. But the fact is this is the only proven effective intervention for adult transmission. And we can’t ignore it. I think it’s unethical to ignore it.”

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- Circumcision: Fact, Fiction and Hype

- The Global Impact of HIV/AIDS

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus