Vampire Books Like 'Twilight' May Be Altering Teen Minds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It's a potentially sucky situation. The vampire craze in teen literature – exemplified by the "Twilight" book series – could be affecting the dynamic workings of the teenage brain in ways scientists don't yet understand.

"We don't know exactly how literature affects the brain, but we know that it does," said Maria Nikolajeva, a Cambridge University professor of literature. "Some new findings have identified spots in the brain that respond to literature and art."

Scientists, authors and educators met in Cambridge, England, Sept. 3-5 for a conference organized by Nikolajeva to discuss how young-adult books and movies affect teenagers' minds.

"For young people, everything is so strange, and you cannot really say why you react to things – it's a difficult period to be a human being," Nikolajeva told LiveScience. The conference, she said, brought together "people from different disciplines to share what we know about this turbulent period we call adolescence."

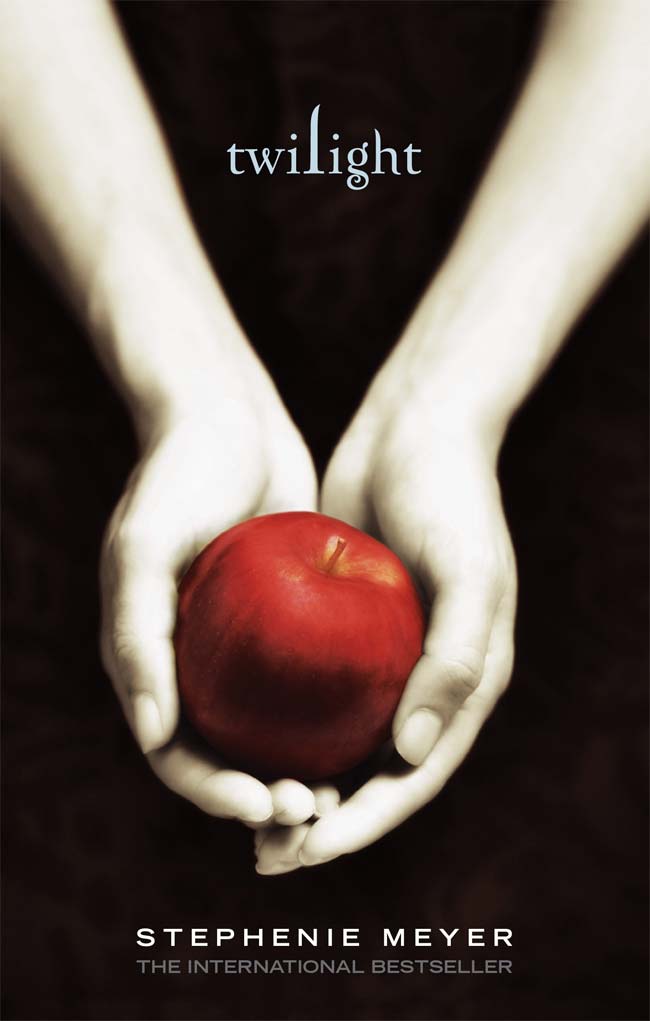

Sessions included "What Is It About Good Girls and Vampires?" addressing the huge popularity of Stephenie Meyer's "Twilight" series and other vampire-themed books. [The Real Science & History of Vampires]

Brain science

Teenagers' minds are more susceptible than adult minds to influence – from peers and experiences as well as from books, movies and music, researchers say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What we have learned over the past decade is that the teenage brain processes information differently than a more mature brain," said conference presenter Karen Coats, a professor of English at Illinois State University who integrates neuroscience into her research. "Brain imaging shows that teens are more likely to respond to situations emotionally, and they are less likely to consider consequences through rational forethought."

That's because the teenage prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for reasoning and risk assessment, goes through a growth spurt before puberty, followed by a period of organizing and pruning of the neural pathways, Coats said.

Linguistic anthropologist Shirley Brice Heath of Stanford University, a keynote speaker at the conference, is studying how reading longer novels habituates the brain toward a greater capacity for sustained attention to visual material.

"What neuroscience opens for us is what happens within the brain during specific activities that take place within identifiable emotional or motivational states," Heath said by e-mail. "For example, we know now that in reading about particular activities (especially those known to the readers), motor-neuronal activity is detected."

Is Bella a good role model?

Attendees at the conference included experts in neuroscience, psychology, art, literature and music, as well as writers such as Meg Rosoff, author of "How I Live Now" and other teen titles.

While teens might be turning the pages of "Twilight" for the plot and romance, other takeaways from the books may be having a lasting impact, too.

The series follows Bella, a teenage girl who falls in love with a much older vampire named Edward. Some critics have argued that Bella's passivity, and the story's abstinence-until-marriage message, are anti-feminist.

"If you look very, very clearly at what kind of values the 'Twilight' books propagate, these are very conservative values that do not in any way endorse independent thinking or personal development or a woman's position as an independent creature," Nikolajeva said. "That's quite depressing."

Dark vs. light

Researchers are interested in how such dark works might affect young minds, and why teenagers are especially drawn to stories with vampires, zombies, and post-apocalyptic and dystopian themes.

"We all remember being teenage is a difficult period, full of contradictions – dark feelings one day, joyful feelings the next. The 'Twilight' books are very much about this, about budding sexuality and not really knowing what you are," Nikolajeva said. "Although I'm not at all a fan of 'Twilight,' I do understand the appeal of it."

Nikolajeva argued that authors have a moral responsibility to include some positivity and hope in works aimed at teens.

"If young people read books where there is no hope at all, it's really damaging," she said. "We need to be aware of young people's being influenced by what they read or watch, the games they play. It all plays a very important role."

Another popular teen book series, the "Hunger Games" trilogy by Suzanne Collins, straddles the line between dark and hopeful, Nikolajeva said. Its themes – a dystopian future where teens must battle to the death on reality TV – appeal to teenagers' dark side, yet its ultimately hopeful message is probably having a good influence on young people, she said.

The conference marked the beginning of a critical dialogue about the role of literature on teen minds and behaviors, she said.

"I think the most important thing to bear in mind is that neither a sciences approach nor a humanities approach gives us the entire picture of how teens interact with literature," Coats said.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus